100 Years Ago Today: Capablanca Vs Lasker 1921

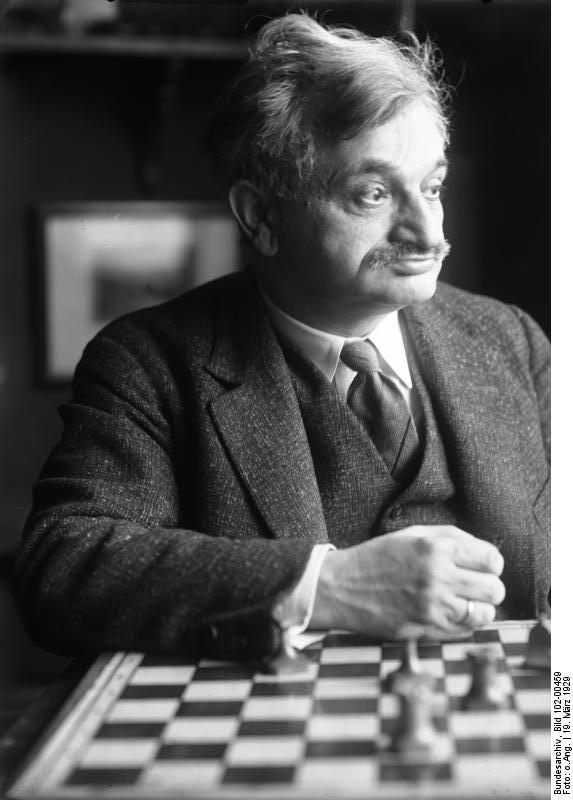

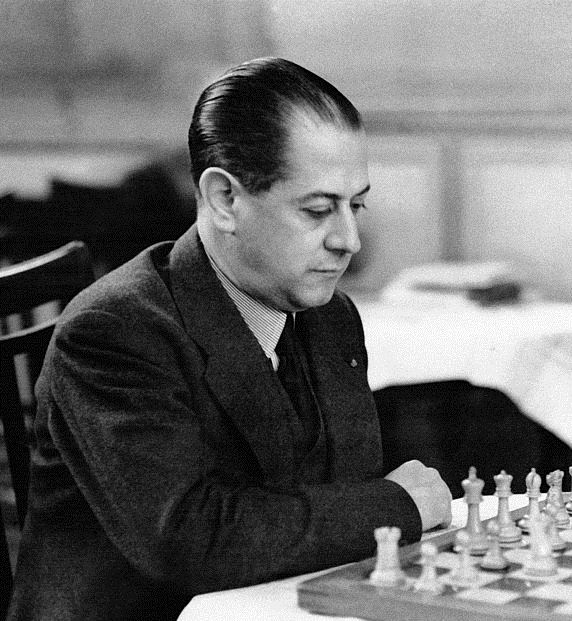

March 15, 1921 in Havana, Cuba—it was like looking into a mirror for Emanuel Lasker. His opponent opened with 1.d4 and he replied with 1...d5. Exactly 27 years prior, it was the 25-year-old Lasker who had White, facing 58-year-old Wilhelm Steinitz in the first game of the match for the world chess championship, which opened 1.e4 e5. This time, Lasker, now 52, was up against 33-year-old Jose Raul Capablanca.

The temperature reached a high of 27 Celsius (81 Fahrenheit) that day, with typical Caribbean humidity of over 90%. The game was hard-fought and eventually settled into a 50-move draw. There was little indication that just 13 games and five weeks later, Capablanca would have won the match and cemented in his place in history with a clean sweep: four wins, no losses, 10 draws.

A match with Capablanca had been a decade in coming for Lasker, still the longest-reigning world champion in history at 27 years. Remember that before FIDE took over the world championship logistics in 1948, the champion had exclusive control over who he would play, and then the two players would negotiate terms.

Lasker, himself, was entering his seventh championship match having compiled a previous record of 45 wins, 11 losses, and 32 draws in world championship games. In part, he had run up the score on strong players who were still much weaker than him, like Frank Marshall and David Janowsky, neither of whom won a single game.

| Year | Opponent | Format | Won | Lost | Drawn |

| 1894 | Steinitz | First to 10 wins | 10 | 5 | 4 |

| 1896 | Steinitz | First to 10 | 10 | 2 | 5 |

| 1907 | Marshall | First to 8 | 8 | 0 | 7 |

| 1908 | Siegbert Tarrasch | First to 8 | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| 1910 | Carl Schlechter | Best of 10 games | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| 1910 | Janowsky | First to 8 | 8 | 0 | 3 |

| 1921 | Capablanca | First to 8 or Best of 24 | 0 | 4 | 10 |

Capablanca originally challenged Lasker in 1911 after making his international debut at San Sebastian, Spain and coming away the clear winner. (Lasker did not participate.) But neither player came away satisfied, either with the conditions or with the behavior of the other.

World War I soon interfered with any chance of Lasker playing either Capablanca or Akiba Rubinstein, who was set to challenge Lasker in 1914 and was arguably the world’s best player in 1912-13, certainly strong enough to have become champion himself had it not been for the Great War.

After the war, negotiations between Lasker and Capablanca remained a tough slog. However, things gradually came together throughout 1919 and an agreement was reached in January of 1920. But the drama did not end there.

Lasker apparently did everything he could to give Capablanca the title, including literally trying to give Capablanca the title. Chess historian Edward Winter, largely using the archives of the American Chess Bulletin, has documented much of the controversy involving Lasker’s resignation of the title and whether it was accepted by Capablanca and/or the press. Although others have tried, it would require too much armchair psychology to determine Lasker’s motivations in becoming the only champion until GM Bobby Fischer to (attempt to) voluntarily concede the title without a match.

GM Ossip Bernstein recalled in 1955 another way in which Lasker seemed to hand Capablanca the match. As Bernstein remembered it, he asked Lasker if the longtime champion had: prepared for the match, rested up beforehand, would take a board to study on the trip to Havana, prepared any openings, or studied Capablanca’s games. Lasker’s answer to all five questions was simply, “No.”

“Without preparation, and handicapped additionally by age and climate, Lasker lost pitifully,” Bernstein continued. Despite Bernstein’s recollection and his characterization of the match, in the early going it was close. Eight of the first nine games were drawn and it wasn’t until the final third of the match that Capablanca broke through and made the final score four-zip.

Despite treading water early, Lasker did end up losing by a significant margin. If it wasn’t the title that worried Lasker, perhaps money was his main concern. Not necessarily that either, but if so, he had a good excuse to be less than prepared for the match.

When the match began, the purse was $20,000, which in 2021 would be about $290,000. More to the point, who won the match was not relevant to the distribution of the money! Lasker was getting $11,000 ($160,000) and Capablanca the other $9,000 ($130,000) regardless of who won.

For Capablanca’s part, six figures for five week’s work is still a good deal, and presumably gaining the title was enough motivation for him anyway. It was a motivation that Lasker, already champion for nearly three decades, did not enjoy.

After the match was underway, benefactors in Havana added another $5,000 to the pool, with $3,000 going to the winner. Adjusted for inflation, the total prize fund ended up at $365,000, of which Lasker took 52% and Capablanca the other 48%.

No matter the particulars, it was a substantial prize fund, but that wasn’t the only way this match portended future ones (although it took some time in both cases). Outside of the somewhat mysterious 1910 match between Lasker and Schlechter, 1921 was Lasker’s first world championship bout to cap the possible number of games.

If neither player won eight games, the leader after 24 would be declared champion. This match was the only one before World War II that indicated that specific number, but it was a best-of-24 format that FIDE settled on for every world championship from 1951-72, as well as the last four matches between GM Garry Kasparov and GM Anatoly Karpov from 1985-90.

And so, the match that began exactly 100 years ago was not only historic, featuring two of the ten best chess players ever, and full of intrigue, but it also helped to shape other world championship matches for decades to come.