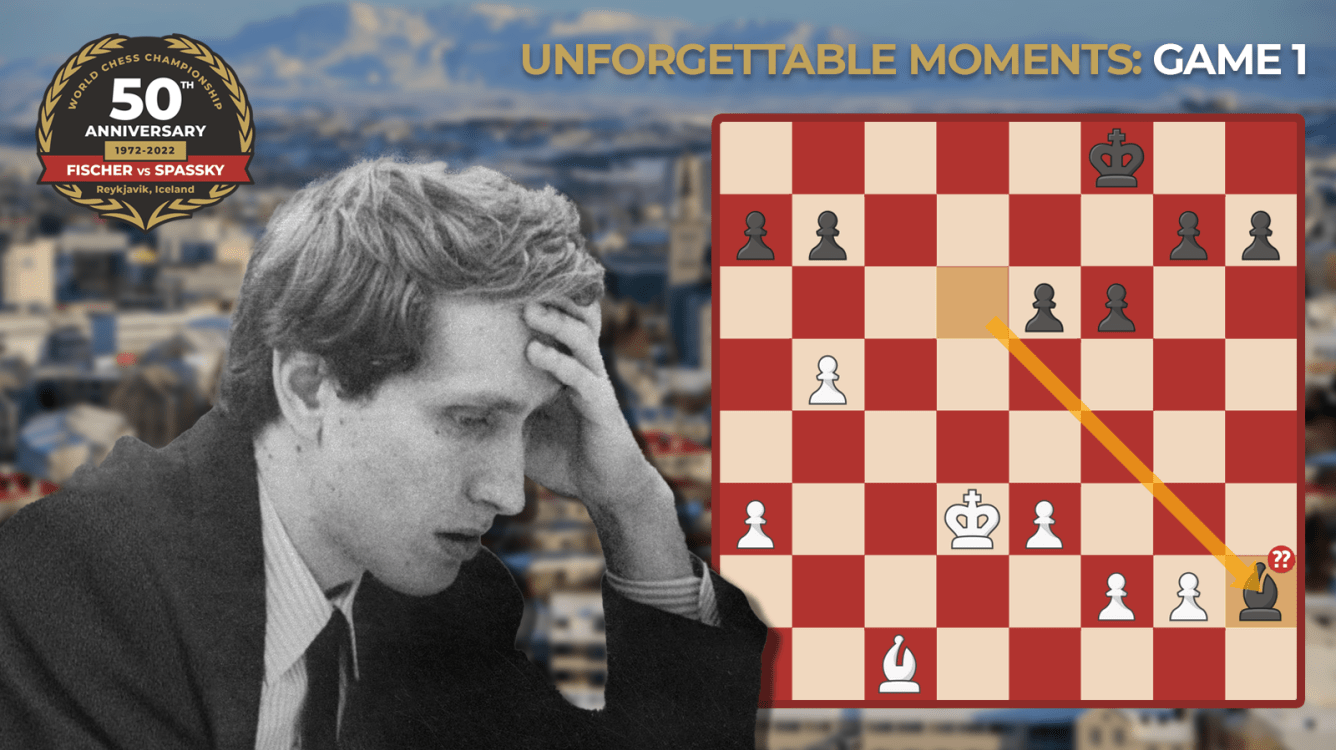

Bobby Fischer Opens Match With Incredible Blunder

Tuesday, July 11, 1972, 5 p.m. local time. The 1,800 spectators at Laugardalsholl applaud as GM Boris Spassky, the reigning world champion, enters the stage. He sits down, makes his first move (1.d4), and arbiter GM Lothar Schmid starts the clock. GM Bobby Fischer isn't there.

With continuous new demands, the eccentric American had complicated the preparations for the match; he had arrived several days late in Iceland and skipped the drawing of colors. Is he actually going to show up?

Spassky, who wears a dark-gray, three-piece suit with a tie, starts strolling onto the stage. He can't have been too surprised about his opponent arriving late for the game. Fischer was known for doing that, for example in the 1971 Candidates final against GM Tigran Petrosian. "To avoid the flashlights of the photographers," was the official reason, but no doubt it was also part of the psychological warfare.

Seven minutes past five. Fischer comes on stage, in haste, shy. Wearing a blue business suit with a tie, he casually but quickly walks to the board with his left hand in the pocket of his trousers. Spassky approaches the board calmly, distinguished.

The players shake hands as the crowd applauds again, thrilled. They're there. The match is starting.

Fischer sits down on his dark, leather office chair—a Charles Eames design executive chair, which he had also used during his match with Petrosian in October of the previous year. He wasn't happy with any of the chairs that were offered to him, until Ed Edmondson, the president of the U.S. Chess Federation and Fischer's manager, found the Eames chair in an office of the Buenos Aires theater.

The same type of chair was flown to Reykjavik for Fischer, but Spassky played on a more regular fabric chair, one that the arbiter was also using. Later in the match, the Icelandic organizers had another Eames chair flown in for Spassky.

Fischer sits down but doesn't make a move just yet. In fact, he puts his head in his hands and starts thinking as if he's looking at a highly complicated middlegame position. He leans back and starts swiveling in his chair.

After 95 seconds, he makes his first move, putting his king's knight on f6. After holding it there for two seconds, he grabs his pen to write down the move.

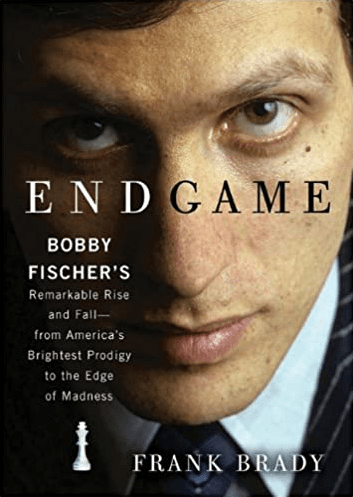

Frank Brady, in his Fischer biography Endgame:

It was a unique moment in the life of a charismatic prodigy in that, to arrive where he was, he'd somehow overcome his objections to how he'd been treated by the Soviets over the years. Everyone knew it, not only in Laugardalsholl but all over the world. As grandmaster Isaac Kashdan said: "It was the single most important chess event [ever]." A lone American from Brooklyn, equipped with just a single stone—his brilliance—was about to fling it against the hegemony of the Soviet Union.

Fischer turns his chair to the left, in the direction of the spectators, then stands up, and walks to the arbiter Schmid. The American protests about the presence of TV cameras and their crew, despite the fact that the two cameras are hidden in special closets, placed about 15 meters (49 feet) away from the stage.

"Spassky remains serene and imperturbable, throughout all this," says a commentator, as the world champion plays 2.c4. Fischer quickly returns to the board, and goes 2...e6.

Most experts considered Fischer to be the slight favorite in the match. London bookmakers favored Fischer 6-5, despite the fact that he had never beaten Spassky yet. The lifetime score was 3-0 in favor of the world champion, with two draws. But wasn't GM Jose Capablanca leading 5-0 (with seven draws) prior to the 1927 world championship match that he lost to GM Alexander Alekhine?

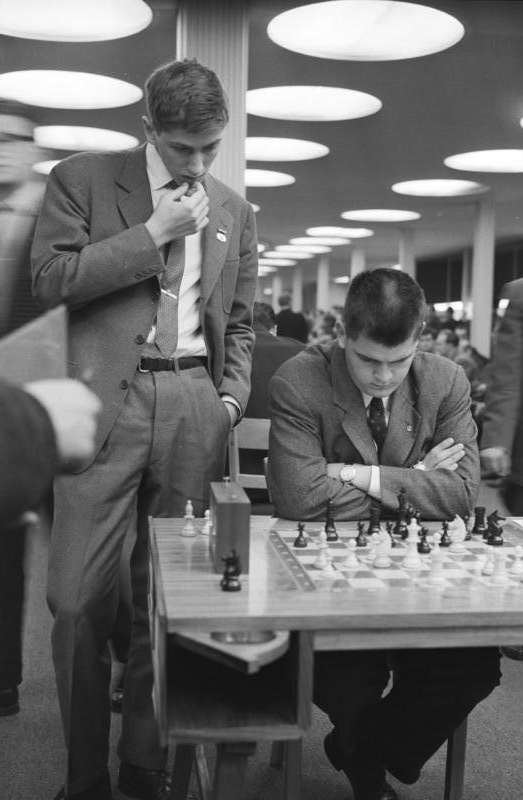

Winning the important game on board one of the Soviet Union-USA match at the 1970 Olympiad in Siegen (Germany) boosted Spassky's confidence, but that changed in 1971. While Fischer had scored resounding victories in the Candidates, Spassky's play had been lackluster.

In fact, the Russian grandmaster probably already felt that Fischer in 1971 was the better player. A quarter of a century later, Spassky would say: "I was the strongest from 1964 to 1970, but in 1971 Fischer was already stronger." But not in that first match game.

In the two earlier games where Spassky opened with 1.d4, Fischer chose the Grunfeld Defense, losing both: at the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, and the aforementioned game in Siegen. For this first game in the Reykjavik match, he goes for the more solid Queen's Gambit setup but then puts his bishop on b4, offering to play the Ragozin Defense.

Position after 4...Bb4.

Spassky, however, chooses to play 5.e3 instead, turning the game into a Nimzo-Indian. By a slightly unusual move-order, the main line of the Rubinstein (4.e3) variation comes on the board.

A giant electronic screen on stage presents the moves. The same internal TV circuit transmits to about 40 smaller television monitors throughout the venue, at restaurants, cafes, and souvenir stands. Sometimes, the screen in the playing hall briefly switches to showing a text: Þögn! / Silence!

On move 11, the game takes a quiet turn when Spassky trades on c5. Many decades later, the queenless middlegame would become a popular way of fighting the Queen's Gambit Accepted, but in this game, it is a sign of a probable quick draw, especially after Fischer's 14...Bd7!—an improvement over the game Spassky-Krogius, Soviet Championship 1958.

In the months before the match, Fischer was known to be carrying with him what was jokingly called "the big red book" (to distinguish it from Quotations From Chairman Mao, nicknamed "the little red book"). Bound in red velvet, it was a copy of Volume 27 of Weltgeschichte Des Schachs and contained a large collection of Spassky's games—all memorized by Fischer.

In the months before the match, Fischer was known to be carrying with him what was jokingly called "the big red book" (to distinguish it from Quotations From Chairman Mao, nicknamed "the little red book"). Bound in red velvet, it was a copy of Volume 27 of Weltgeschichte Des Schachs and contained a large collection of Spassky's games—all memorized by Fischer.

As more and more pieces get traded, Spassky's king approaches the center of the board. He is slightly more active in what is now a bishop endgame, but everyone expects the game to end peacefully and very soon.

Then, something unbelievable happens. With plenty of time on the clock, Fischer takes the pawn on h2, and does so fairly quickly.

What is this? Doesn't the bishop get trapped there? How... why?

GM Edmar Mednis later said: "I couldn't believe that Fischer was capable of such an error. How is such an error possible from a top master, or from any master?"

I couldn't believe that Fischer was capable of such an error.

— GM Edmar Mednis

GM Garry Kasparov, in My Great Predecessors Part IV: "In a dead drawn bishop endgame he suddenly captured a 'poisoned' pawn with his bishop—apparently he wanted to show Spassky that he could play against him 'as he pleased', but... he miscalculated.

"There is only one way to explain such a simple blunder and the missed draw: it was very hard for Fischer to get into his stride. I think that his mental state before the match was largely caused by the fact that he was not yet really ready to play, that he had as though not woken up..."

Position after 29.b5.

After 29...Bxh2??! the game continued 30.g3 h5 31.Ke2 h4 32.Kf3 Ke7 where, earlier in his calculations, Fischer had probably been planning 32...h3 33.Kg4 Bg1 34.Kxh3 Bxf2

Position after 34...Bxf2 (analysis)

It is widely believed that in this position that could have appeared, Fischer missed White's option 35.Bd2!, when the black bishop is trapped.

AP footage of the first game of the match.

Fischer's move looks like a beginner's mistake. He indeed loses his bishop, but gets two pawns for it, and during the game, it's not immediately clear how Spassky will win. Is it possible that the challenger is going to get away with it?

Meanwhile, the American continues complaining backstage about the cameras. And then, after Black's 40th move, Spassky decides to adjourn the game.

Position after 40...f4.

The time control in the match was two and a half hours for 40 moves followed by 16 moves every hour, with an adjournment after a session of a minimum of five hours. However, the game hadn't run for five hours yet.

Spassky insists on adjourning, thereby taking a loss of 35 minutes on his clock. He seals his move, puts it in the special envelope, and gives it to the arbiter. It is 10 p.m. local time, but the sun is still shining outside due to Iceland's relatively close proximity to the arctic circle.

The match schedule planned for three games a week, with games starting at 5 p.m. on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Sundays. Unfinished games would be resumed the next day. Saturday, Fischer's sabbath, was a rest day.

The players had a full night, morning, and early afternoon to analyze. While Fischer might have been helped by his second GM William Lombardy, Spassky had a bigger team to assist him: GM Efim Geller, GM Nikolai Krogius, and IM Iivo Nei.

According to Brady, Fischer "appeared at the hall looking tired and worried."

The arbiter executes Spassky's adjourned move on the board and starts the clock. Fischer quickly replies and then leaves backstage to once again complain about the cameras. While Spassky makes his next move, Fischer eventually manages to convince the organizers for the cameras to be dismantled, while Fischer lets his clock run for 35 minutes.

As the game progresses, Spassky shows impeccable technique, helped by the overnight analysis of his team. He plays for Zugzwang, forcing Fischer to move his e-pawn. Spassky soon captures Black's g-pawn, and then also the e-pawn. Black will never reach a fortress.

On move 56, after a bit over an hour of play, Fischer stops the clock and resigns.

This is the first game of the most anticipated match in chess history. Generations have fallen in love with the game thanks to this magnificent duel. On the one hand, we have the World Champion Boris Spassky: the Soviet bon-vivant, a survivor of the Siege of Leningrad, who had a secret admiration for Bobby Fischer, and who feared nothing. On the other side, Bobby Fischer: the wandering genius, a contender for the title since the early 1960s, now finally arriving to claim what he thought was rightfully his.

My father was one of the many chess players around the world who fell in love with chess thanks to this match. The reverberations of Reykjavik reached São Luís, an island in the northeast of Brazil. 14 years later he would teach me how to play chess. For all that, I feel honored by the opportunity to revisit the great games of the match. Much has been written about them. It is certainly the match with the largest amount of analysis pages ever published. So that my comments are attractive to readers, I will try to highlight two points: 1. The state of opening theory at that time, so that readers will have an idea of the level of preparation Spassky and Fischer had. 2. Discoveries that change or at least add something relevant to existing analysis. The first game, as is well known, has one of the most discussed moves in chess history. Let's see what happened.

In the years to come, this fascinating endgame would be analyzed thoroughly, most notably by GMs Jan Timman and Fridrik Olafsson. GM Jon Speelman dedicated a full chapter to it in his 1981 book Analysing the Endgame, while Kasparov, in his notes to the game, further quotes GMs Mikhail Botvinnik, Robert Byrne, Paul Keres, Edmar Mednis, Cecil Purdy, Ludek Pachmann, and Lodewijk Prins.

The general conclusion was that 29...Bxh2 was indeed a blunder, but with his 36th move, Spassky had given Fischer a chance to hold. However, as GM Leitao's analysis shows, 29...Bxh2 in itself was not a losing move just yet.

The match had started, and Spassky immediately took the lead. In a dramatic way, he would soon double that lead without a single move being made—a story that will be told in the next article of this series.

Previous 50th Anniversary Fischer-Spassky Content: