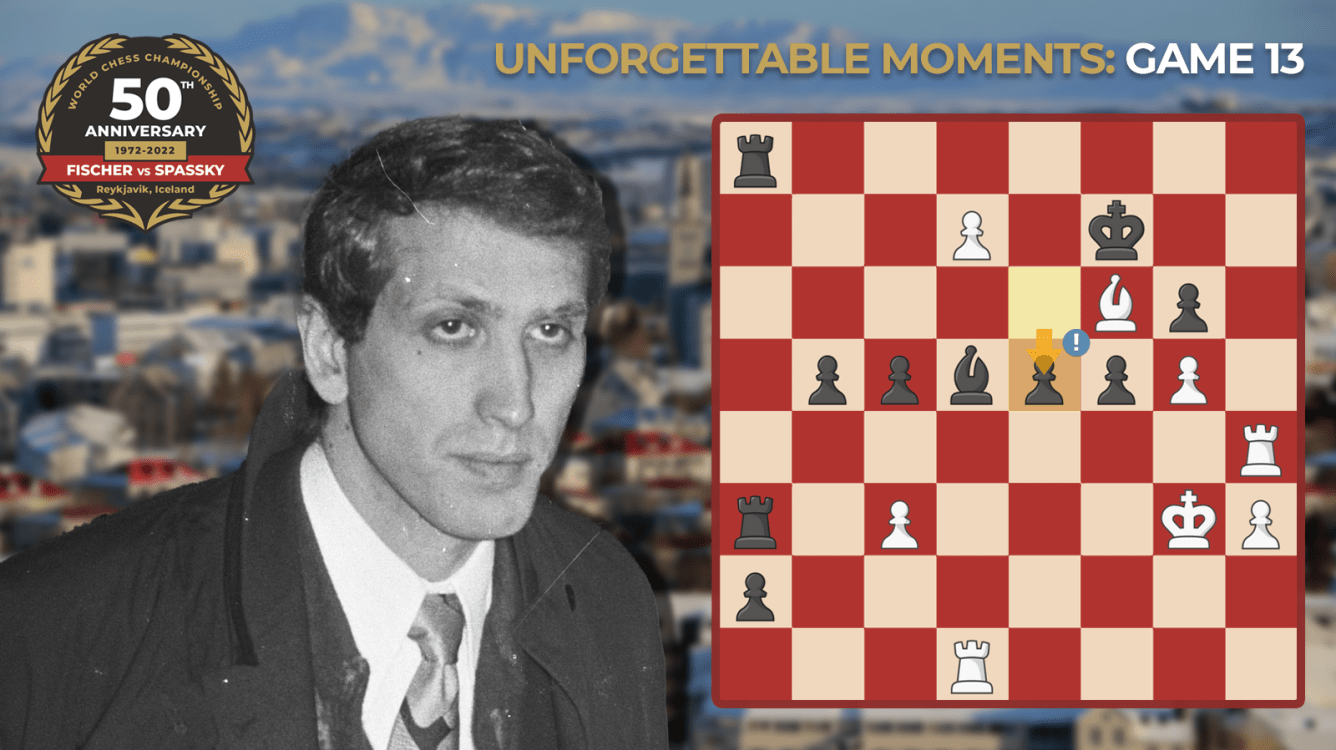

Bobby Fischer Wins A Chaotic Brilliancy

Game 13 was ultimately the most chaotic, bizarre, and epic game of what was a chaotic, bizarre, and epic 1972 World Championship match. From Alekhine's Defense on move one to the unusual final endgame position of three pawns overwhelming a piece on move 74, nothing about this game was typical. At the end of it all, the match was effectively (but not officially) over.

Entering this game, the match schedule had reached its halfway point with GM Bobby Fischer leading GM Boris Spassky 7-5 (five wins to three with four draws). For the first time since Fischer's game two forfeit, however, momentum was on Spassky's side. He won game 11 with White, drew game 12 with Black, and now had White again for the 13th game.

A second straight win for Spassky with White would really put Fischer under pressure, while a draw would also be a solid outcome for Spassky: Given his status as the defending champion, he would keep his title should the 24-game match end tied 12-12, and so there was still enough time that keeping the deficit to two games would be an achievement.

When the game was adjourned, the draw seemed in order. Fischer pulled an all-nighter trying to find a win, to no avail. Spassky's seconds were equally sure that there was nothing yet to play for.

Despite all that, and the objective truth of the situation, imbalanced positions still pose problems. This was not a symmetrical bishop vs. bishop ending, and as Fischer had proved in the first match game, even those relatively simple situations can be botched.

The position only got increasingly absurd as the moves kept coming on August 11. Fischer ended up with three, then four pawns for a bishop; Spassky boxed in Fischer's rook. Although the position remained equal, one might have sensed that something was about to break. And break it did, when Spassky blundered on move 69. Forced to release Fischer's rook and lose his last pawn in the process, Spassky resigned five moves later.

This is my favorite game of the match. A titanic battle with moments of beauty in all three phases of the game. An exotic opening, in which Fischer once again goes to great lengths to surprise the formidable Soviet team. A middlegame with material imbalance, highlighting the two styles of play: Fischer, with his straight-to-the-point game and Spassky, the initiative player by nature. And the endgame—this is the best part. A game of chess is rarely as beautiful and well played as in this finale. After the postponement, we see a perfect play by both players for many moves. Fifty years later and the computer still approves of the analysis made by Fischer, Spassky, and the Soviet team. After so much struggle the game ends suddenly, after a serious mistake, showing that even the great players are fallible. Like a three-hour movie or a thousand-page novel, not every moment is top-notch, but what matters is the impression it leaves as a whole. This is a game to be seen, reviewed, and appreciated.

Despite the unusual nature of the endgame, consensus is this was a position he should have held. Spassky agreed. He stayed at the board long after Fischer had gone, trying to figure out what had just happened.

It was a shame for Spassky, not just because the match was essentially over now, but also considering how well he had to play to hold the draw for so long. The Chess.com computer credits Spassky with a whopping 16 great moves, 15 of them on turns 42-62. Those are moves the computer sees as the only good ones in a given position.

In any event, no less a figure than GM Mikhail Botvinnik was impressed by Fischer's game, calling it his "highest creative achievement" (according to GM Andy Soltis).

More importantly for Fischer, after this marathon, the match score was now 8-5 with 11 games to go. He could start playing "prevent defense"—avoid any catastrophic mistakes and the match would soon be his. Avoid such mistakes he did: The next seven games were all drawn.

Fischer now had four games to acquire the one single measly point needed to take the crown. We'll see you then.

Previous 50th Anniversary Fischer-Spassky Articles:

- Boris Spassky Smashes Fischer's Najdorf

- Bobby Fischer Wins Positional Masterpiece

- Bobby Fischer Ties The Match

- Everything You Need To Know About Bobby Fischer

- Everything You Need To Know About Boris Spassky

- Bobby Fischer Scores 1st Win

- Bobby Fischer Forfeits Game 2

- Bobby Fischer Plays An Incredible Blunder

- 50 Years Later: Why Fischer Vs. Spassky Was The Greatest World Championship Match

- Why The Match Of The Century Almost Didn't Happen