Playing Against The Najdorf: The Adams Attack

In recent years, a strange little move has become surprisingly popular in combating the famous Najdorf Defense of the Sicilian: 6.h3.

Personally, I have used this move since 2000, when I finally had to admit that it was more correct than the 6.Rg1 I had sometimes used before.

At that time, 6.h3 was a fairly obscure move, almost never seen on the top level. Nobody likes it when his pet lines become popular and thus lose their surprise value, but it would be funny if the chess world came to the conclusion that not only is the small pawn move 5...a6 the best opening (as many people might claim), but its best answer is another tiny pawn move on the other side of the board: 6.h3!

This move is sometimes called the "Adams Attack" -- a fact that I was only vaguely aware of despite using this opening for 15 years. It is named after Weaver Adams, an American master who was indeed the first one to use this move and presumably was its inventor.

Adams passionately believed that White should win by force with 1.e4, writing a book and publishing many articles to prove his belief, and his "refutation" of the Najdorf was indeed, paradoxically, the little 6.h3 move.

It was later also used by Norman Tweed Whitaker, an international master who was also one of America's strangest chess characters in an era when the chess world was more freewheeling. Suffice to say, he spent time in Alcatraz prison due to his involvement with the Lindbergh kidnapping.

.jpg/300px-Norman_Tweed_Whitaker_(mug_shot,_1932)/http/d81e6496db.jpg)

What is the point of this obscure little pawn move? Well, obviously White prefers g2-g4, without giving up castling rights as 6.Rg1 does. With Black uncastled, why begin advancing the g-pawn?

In fact, g2-g4 is not merely the beginning of an attack on the kingside, but also a positional maneuver. By playing g4, White is fighting for the critical square d5 in two ways: by preparing the fianchetto of the bishop, and also menacing the knight on f6, since g4-g5 will constantly be in the air.

Since the Najdorf itself delays Black's development slightly, most of the early attacks tried to wipe it out with rapid development -- 6.Bg5, 6.Bc4, 6.f4, and so on.

The Adams Attack does not do this; however, by making this strategic accomplishment, achieving g2-g4 in one move and gaining a grip on the d5-square, White is challenging Black to exact "revenge" by opening the center before Black is ready -- White hopes.

In addition, one of the points of the Najdorf move 5...a6 is in the preparation for ...e7-e5. 6.h3 makes a sort of limited prophylaxis against this move. Thus after 6.h3, White can meet 6...e5 with 7.Nde2 (since the e2 square is not blocked).

Then harmonious development can follow with g2-g4, Bg2, Ng3, and so on. Ideally, White will not only dominate the d5 square, but also can use the f5 square while having a ready-made attack on the kingside. Clearly Black can still play 6...e5, but in a strange way White's 6.h3 makes Black question his usual Najdorf move.

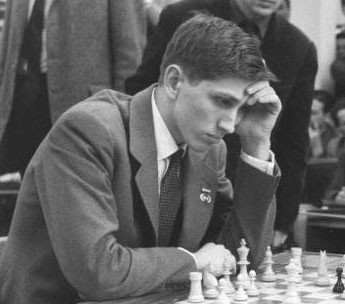

None other than Bobby Fischer took up the strange move of his two unusual compatriots (Weaver Adams was also a very colorful character).

Although Fischer usually preferred to combat the Najdorf with 6.Bc4, he also used 6.h3 on three occasions; probably he first got interested in the move when it was played against him by William Lombardy in a 1958 game.

Fischer won one of the Adams Attack's most famous games against the namesake of the Najdorf Defense, Miguel Najdorf:

Perhaps in those days Fischer innately understood the value of this little move, which didn't really become popular until top players' computers showed its value much later.

So 6.h3, for the most part, slept for quite a while, until it suddenly awoke in 2008. In the intervening years, it was hardly used by top players. The best player who used it consistently in those days was probably Viktor Kuprechik, although some other strong players used it occasionally.

Probably one of the main reasons why 6.h3 was not more popular was because of the following position, where Black has met 6.h3 in the natural way by 6...e6 7.g4 b5 8.Bg2 Bb7.

Black answered White's kingside fianchetto with his own. Now apparently Black threatens 9...b4, chasing the knight away, followed by capturing the e-pawn.

Thus most players with White played moves like 9.a3, 9.Qe2 (both slowing down his buildup a little) or 9.g5 (prematurely allowing the ideal rearrangement ...Nb6 followed by ...N8d7). It appeared that Black's setup was an ideal counter to 6.h3.

But in early 2008 there was a major development. On the same day, at the Melody Amber blindfold/rapid tournament, Magnus Carlsen and Sergei Karjakin simultaneously played 9.0-0 against Boris Gelfand and Loek Van Wely, respectively.

It seems that the Carlsen-Gelfand game was blindfold, while the Karjakin-Van Wely game was rapid. While Gelfand prudently responded 9...h6 (Carlsen won in crushing fashion nevertheless), Van Wely "bit" and played 9...b4.

Karjakin responded with the thematic 10.Nd5!!

While Nd5 sacrifices against the Sicilian have been known for a very long time, this was the first time someone had played it in this specific position. As it turned out, the seemingly slow "extended fianchetto" was an ideal preparation for the thematic sacrifice. Karjakin won in decisive fashion:

Shortly thereafter, Hikaru Nakamura also used the same 10.Nd5 sacrifice to win a game against Nikolai Ninov. He followed it up in a slightly different (but also strong) way.

Since this development, 6.h3 made a big comeback and you can find debates on it between top players.

In part two, we will look at the different ways Black has used to combat this system.

RELATED STUDY MATERIAL

- Read GM Smith's last article: The Scandinavian Defense: Modern Play.

- Watch GM Sam Shankland's definitive video series on the Najdorf.

- Take a lesson on the Najdorf in the Chess Mentor.

- Solve some puzzles in the Tactics Trainer.

- Looking for articles with deeper analysis? Try our magazine: The Master's Bulletin.