The History Of Cheating In Chess

Chess, like any form of competition, has always seen its fair share of unfair play. From prearranged draws to computer cheats, where there's the will for ill-gotten gains, players have found the way. Whether the side being cheated can prove it or the accused party is actually innocent, cheating rears its ugly head repeatedly in the history of chess. Read on for just a sample.

- Cheating The Public

- Match Fixing

- Piece Manipulation

- Assorted Aspersions

- Engine Cheats

- Accomplices

- Conclusion

Cheating The Public

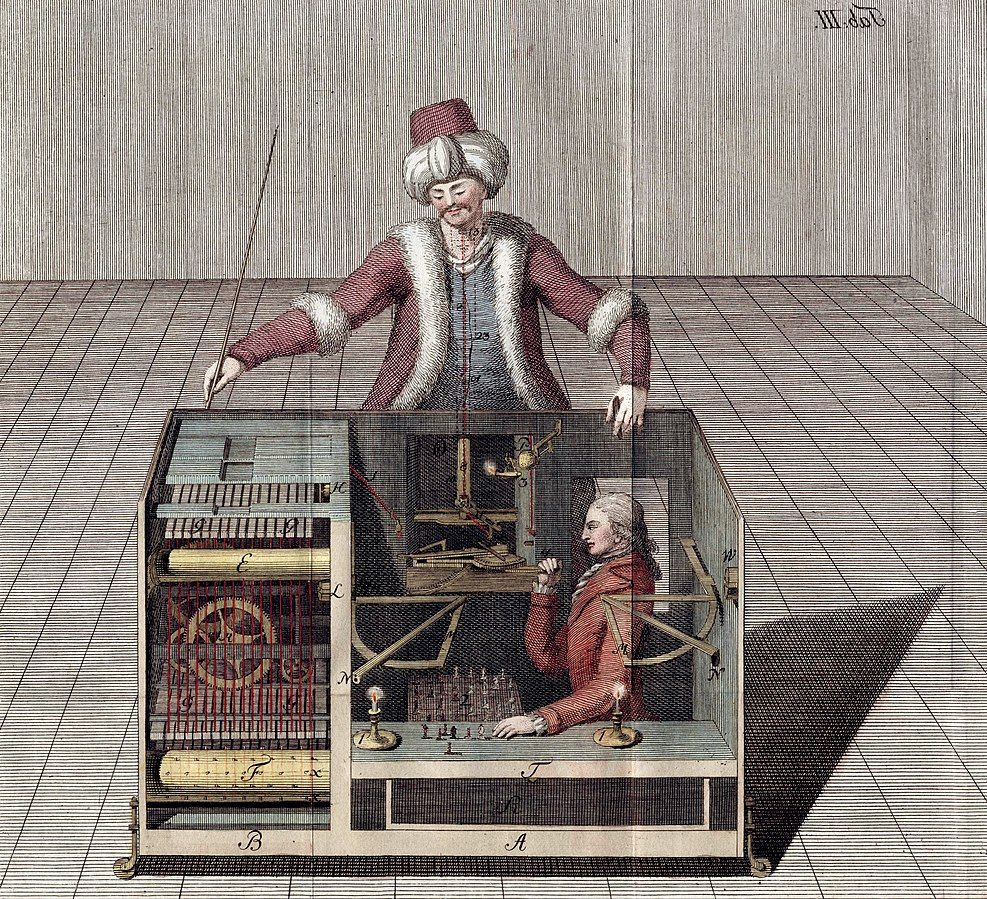

In the 18th and 19th centuries, some creative charlatans devised complicated devices which they portrayed as chess-playing machines. The main difference between these machines and modern engines is that the automatons, as they were called, were, to put it politely, total horse hockey.

If you consider deceptive hoaxes a form of cheating, the designers and operators of these devices are arguably the first chess cheats we know of.

Match Fixing

Colluding with or paying someone for a draw before a tournament game even begins in order to preserve standing or energy and improve the overall odds of winning a better prize dates back almost as far as the chess tournament itself. The American eccentric Preston Ware (how eccentric? well, the move 1.a4 is named for him) brought this flavor of deceit into the public view in 1880, not even 30 years after the first international tournament was held, and had apparently been involved since 1876. You can read here for the detailed expose.

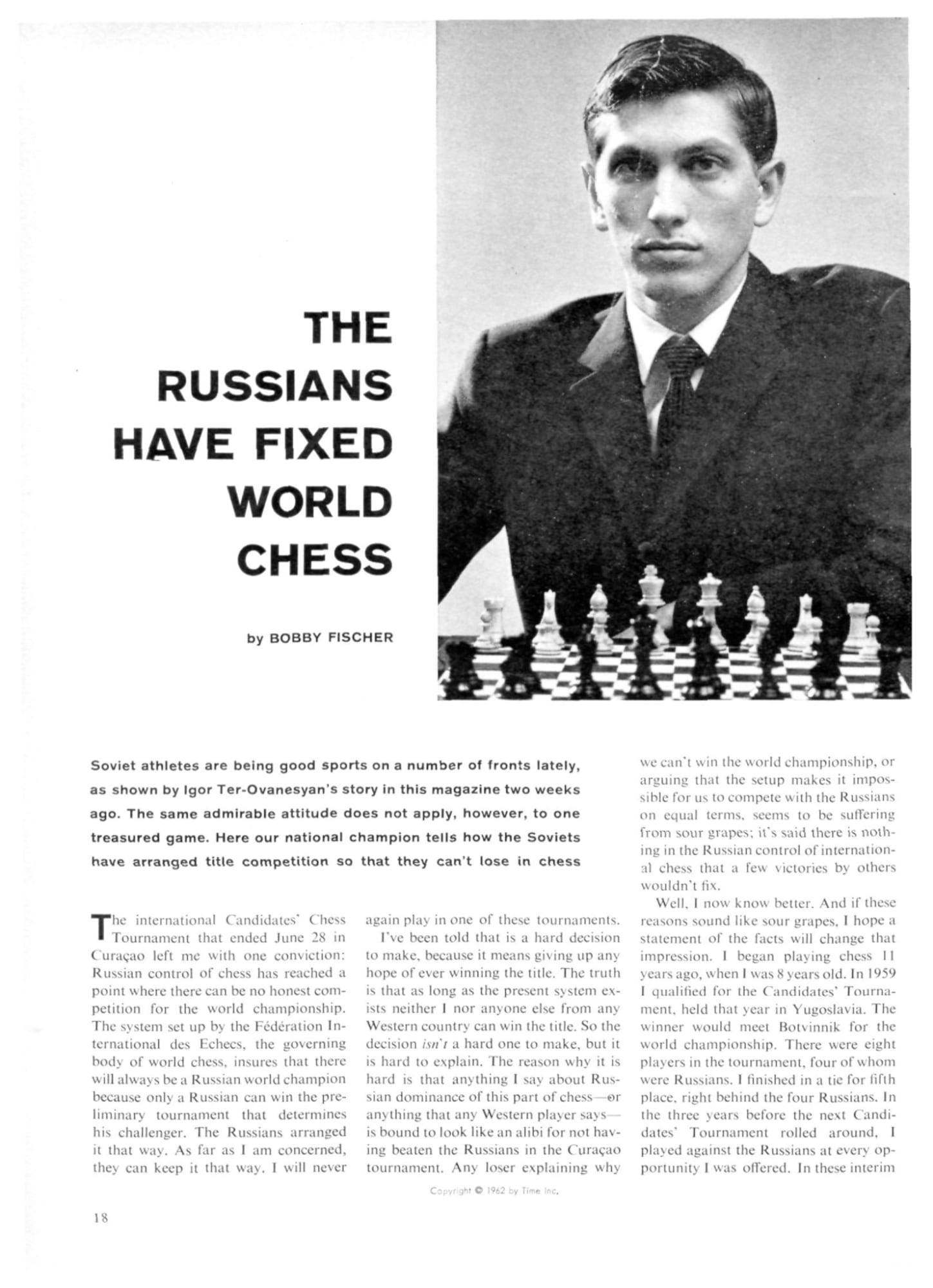

But the most infamous accusation of collusion came at Curacao in 1962.

GM Bobby Fischer, trying to reach the world championship 10 years before he actually did, finished in fourth place at the 1962 Candidates. Afterward, he accused the top three Soviet players—GMs Tigran Petrosian, Efim Geller, and Paul Keres—of making easy draws so that they could focus their energies on Fischer.

The current view is that Fischer was more likely correct than not. Even at the time, his accusations were taken so seriously that the Candidates format was changed. Instead of a round-robin, it would be played as an elimination tournament starting in 1965.

Piece Manipulation

Short of faking games, the most notable form of cheating prior to the chess engine involves the touch move rule, which requires players to move a piece as soon as they touch it. A player can also not let go of a piece on a new square and then change its destination. Now, in most cases, if a player touches a piece that has zero good moves, they admit defeat. But some players are more brazen than others.

GM Milan Matulovic committed the first widely-known public example of this in 1967. As chess historian Edward Winter quotes from IM Harry Golembek's contemporaneous report: Matulovic, "in sore straits against the Hungarian [GM Istvan] Bilek, played a move that would have lost out of hand.... He took the losing move back, replaced it by another much better move, and eventually got away with a draw. His opponent, Bilek, protested three times to the arbiter, who, however, not having heard or seen the first part of this incident, ordered him to continue play."

More than 35 years later, it happened again. In 2003, GM Zurab Azmaiparashvili, who later became known for other injudicious behaviors, also touched one piece and then moved another. Unlike Matulovic's opponent, who protested to no avail, Azmaiparashvili's opponent froze and allowed the infraction to proceed unchallenged.

It's not always as obvious as those two cases, and some may point to the 1994 incident where GM Garry Kasparov briefly released a piece against GM Judit Polgar before moving the same piece to a different square. It happened so quickly, about a quarter-second, that it's not clear even Kasparov knew what he was doing. Matulovic and Azmaiparashvili, however, not only let go of their pieces, they moved completely different ones!

In a more creative exercise of piece manipulation, GM Bator Sambuev may or may not have intentionally hidden a piece in 2017. If intentional, it was an angle shoot at best and cheating at worst.

And in unregulated games, of course, this kind of action is easier to pull off... unless you're playing against a grandmaster who's seen it all, like GM Maurice Ashley.

Assorted Aspersions

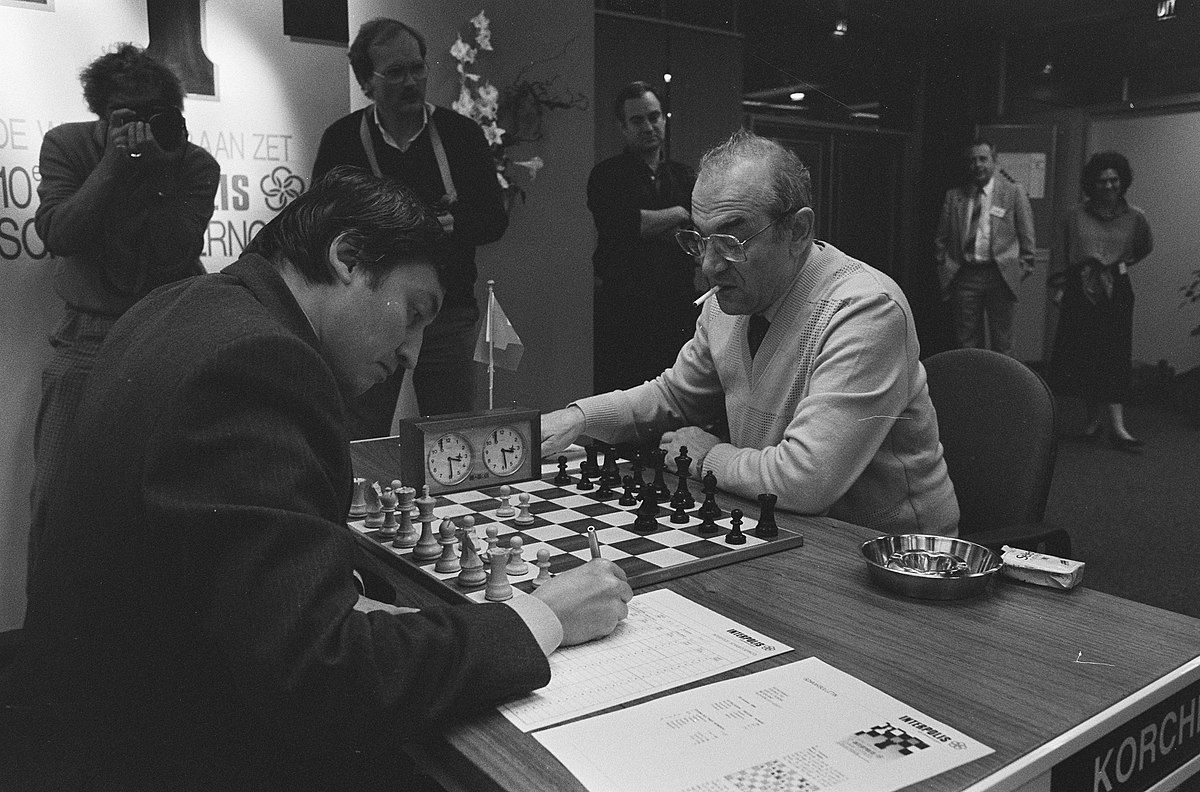

Not every accusation of cheating ends up being correct, and some have bordered on the bizarre. Unsurprisingly, when the stakes are at their highest, in the world championship, tensions can run highest. Two famous cases happened in 1978 and 2006.

The two weirdest stories from the 1978 World Championship between GM Anatoly Karpov and GM Viktor Korchnoi involve a hypnotist and yogurt. (We did say weird.) As Mark Weeks recounts, the cheating accusation involved yogurt, which Korchnoi's side claimed could be a color-coding scheme to transmit information, and it's not clear this complaint was completely serious.

A much more serious accusation came in the 2006 World Championship between GMs Vladimir Kramnik and Veselin Topalov. After Topalov fell behind 3-1 in the match, his camp accused Kramnik of cheating from the bathroom. (More on this general form of cheating later.) The accusations were unfounded and Kramnik eventually won the match, although with arguably much more difficulty than should have been required.

Looking back on it with Chess.com in 2019, Kramnik stated, "For me, I know I have done absolutely nothing wrong—not legally, not morally. But his behavior was awful. OK, it was mainly done by his manager, but if you are more than 10 years old, you have to take responsibility for what your team is doing." That manager was IM Silvio Danailov, who was possibly retaliating for 2005 accusations against him and Topalov made by GM Alexander Morozevich, one of Kramnik's assistants in the 2006 match.

As Topalov may or may not have known, winning games is never by itself evidence of cheating, but that didn't stop other players from hounding WGM Mihaela Sandu after she started the 2015 European Women's Championship with five straight wins. There was so little evidence, however, that the eventual winner of the event faced a ban, not for cheating but for leading the accusations against Sandu, who eventually finished with a 6/11 score after losing her last five games.

Engine Cheats

With the advent of the chess engine, cheating has become more direct. Instead of fixing tournament results with draws, players now try to win games with computers. Engines haven't always been the unstoppable menaces that they are today, but they have already been plenty good enough to change the outcome of human games for decades, hence accusations go back to 2006 and even earlier.

(That's not to say the prearrangement has disappeared. For example, GM Sergey Karjakin's 2002 run to the record for youngest grandmaster ever recently drew scrutiny.)

The earliest known case of a potential computer cheater, in fact, goes all the way back to 1993, when a player going by the name of John von Neumann showed up at the World Open, spent most of his time staring at the ceiling or into space, made a draw with a grandmaster anyway, lost another game on time on move nine, demonstrated zero chess skill outside of physically being able to move pieces to squares but scored 4.5/9 anyway, and even had an unknown person come over at one point to write down a move for him—then scampered away without his prize (for the highest unrated finisher) after the organizers dared him to solve a back-rank mate-in-two puzzle and he would not even try.

The most blatant example yet of computer cheating, however, was committed by erstwhile GM Igors Rausis in 2019. He was photographed conferring with a phone engine in a bathroom stall and banned for six years as a result, losing his title in the process.

However, Rausis is not the first player caught using a phone in the bathroom: GM Gaioz Nigalidze did the same thing four years prior. In an incredible irony, it was GM Tigran L. Petrosian who suspected Nigalidze and tipped off the arbiter, who found the phone, complete with the game position on the screen.

The irony, of course, is that five years later Petrosian himself was caught cheating in what, at the time, was probably the biggest chess cheating scandal since Fischer's 1962 complaints. Online chess was booming, and Petrosian's response to the initial accusation from GM Wesley So has been repeatedly memorialized on the internet by this point.

Accomplices

Just picking up the phone and checking out a position is about the easiest way to cheat, but that means it's also the easiest way to get caught. Far more complex are methods like the one GM Sebastien Feller was alleged to have used in 2010 before receiving a 33-month FIDE ban in 2012: IM Cyril Marzolo referred to a computer offsite and texted moves in code to GM Arnaud Hauchard, who stood in the playing hall in a coded position to suggest a move to Feller. The 1993 von Neumann case was also most likely an incidence of an accomplice transmitting engine moves to a player.

Even more sophisticated schemes are theoretically possible as well. This video demonstrates one:

There was also the story of Borislav Ivanov, who from mid-December 2012 through mid-April 2013 was enjoying a meteoric rise, but aroused suspicions that he was using a hidden electronic device on his back or in his shoe. In October 2013, Ivanov "retired" from chess in the middle of a tournament rather than undergo an inspection. By December, he was permanently banned by Bulgaria's chess federation.

Conclusion

The Ivanov incident was already almost 10 years ago. As technology improves, as computers get better at chess, and electronic devices get smaller, concerns over unfair play will continue to grow.

However, cheating at chess goes back decades, so while the fight against it may be getting harder, it's not a new fight.

What do you think are the most egregious examples of chess cheating in history? Let us know in the comments!