What I Learned From The Chess Patriarch

GM Mikhail Botvinnik was the sixth World Chess Champion and is generally accepted as one of the best players of all time. Known as "the Patriarch," he worked with and trained many promising masters, grandmasters, national champions, and world champions including Anatoly Karpov, Garry Kasparov, Vladimir Kramnik, and myself. My acquaintance with the Patriarch took place at a very young age when I saw the following position:

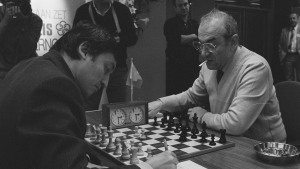

I met the Patriarch in person at the first session of the Botvinnik-Kasparov school in Pestovo, Moscow region in 1986. I do not know why, but I immediately developed a good relationship with the Patriarch. During dinner, we were often sitting at the same table and had many long talks.

I remember Botvinnik being especially impressed with my ability to play the endgame, which he considered the first sign of great chess talent. The patriarch believed that his games were classics, and that everyone should know them. During training sessions he would often say things like: “I played like that. Do you know who invented this? Flohr."

At the same time, I met Garry Kasparov who had recently become the world champion. Altogether, I attended five sessions of the school. I remember that I wanted to ask Botvinnik about his game against GM Igor Bondarevsky, but for some reason I never did:

I arrived to the second session of the school as the U-16 world champion. A television crew came and asked Mikhail Moiseevich the question of what he thought about the chess future of Vladimir Akopian. Kasparov describes this episode in his book My Great Predecessors part 2:

"I remember with a smile how Armenian television turned up at the first lesson and asked Botvinnik a question: 'What do you think, will Akopian become world champion?' Volodya Akopian, a pupil at the school was then 14, while I was 22. I had just won the title and was intending to play for a long time to come... As usual, after thinking for several seconds, Botvinnik slowly and forcibly stated: 'If he works well, he will become world champion!'...

I looked at Mikhail Moiseevich in astonishment: yes, Akopian would probably become a good grandmaster, but... world champion? But this was the directive of a wise teacher: you have to work! And on the other hand, he had a subtle and very distinctive sense of humor."

First of all, I have to say that memory clearly deceives Kasparov in this instance, since the television crew that “turned up” was not Armenian, but the Central Television station and those who conducted the interview were the famous Russian sports commentators Georgy Surkov and Nikolai Popov. Moreover, Mikhail Moiseevich chopped in: "If he works like Kasparov, to the chagrin of Kasparov, he will become the world champion."

If he works like Kasparov, to the chagrin of Kasparov, he will become the world champion.

— Botvinnik on Akopian

Apparently, this very phrase aroused the wrath of the newly-minted champion, although I had nothing to do with it. As for the work, I never worked on chess like Kasparov, because (in no way diminishing the merits of Garry) I always shared the opinion of great chess players like GM Boris Spassky, maintaining that the most important thing in chess still remains to play over the board and not a demonstration of home analysis.

But in general, I should proudly say that Botvinnik certainly distinguished me among other students of the school. Thus, he always wrote my homework (sessions were held twice a year, and at the end of each session every student received their home tasks for six months) by hand, although all the others received it in hard copy.

At school, the students would jog in the morning. It was cold, snowy, and besides getting up early in the morning was always a hell of a job for me. Igor Botvinnik ran with the guys, he was a relative of Botvinnik and the main organizer of the school. And I was tired after recently winning the U16 World Championship.

But Mikhail Moiseevich treated it like this: it is necessary, and that's it! One day I still did not go running, risking incurring the wrath of the Patriarch. Mikhail Moiseevich did not run himself, but he found out about everything. And later they told me about Botvinnik's reaction: "Let all the guys run, and let Akopian sleep!"

Let all the guys run, and let Akopian sleep!

— Botvinnik

In the intervals between sessions, he sent letters through Igor Botvinnik with very valuable advice and instructions. Traveling through Moscow, I visited his house and almost always called him. One day during a telephone conversation while we were talking about one of the students of the school, Botvinnik asked: "So she did not see my game with Lisitsin?" I replied, "I do not know, Mikhail Moiseevich, she probably did not," although I did not really recall such a game myself.

Before going to the U16 World Championship, Botvinnik had asked me to find time to visit him in Moscow. I went there and received important advice. He told me that he had no doubt that I would win the tournament but he also advised me not to lose a single game. He said draws are OK but losing a game would not only lose me a point but it could also affect my psychology. It would have been more difficult to play the rest of the games after a loss. In short, don't lose, make draws and you will win the number of games you need for first place. As simple as that!

I did exactly as he suggested. I started off well with 3.5/4 and then I made some draws with all of the strong title contenders. In this time, leaders were changing while I was always half-a-point behind. Towards the end, I won several games and by the penultimate round, I suddenly saw that I was leading by a full point. It was an 11-round tournament and I only needed a draw in the final round. I had the white pieces and it was easy to secure a draw and, with it, the World Under-16 title. In the tournament, I won six games and drew five. Botvinnik’s advice worked wonders for me.

Botvinnik wrote many interesting chess books on different topics. But what I liked most were his annotations to his own games. They were both simple and instructive. Here I would like to share with the readers the famous endgame from the decisive 23rd game of Botvinnik - Bronstein world championship (1951) match. The endgame was annotated by Kasparov in his aforementioned book and I elaborated on his analysis in my article for "64 chess review" in 2005.

Sometime around 2004, Igor Botvinnik asked me to write annotations for five games from the Botvinnik - Petrosian world championship (1963) match. While looking through the other games of the match, I found a very interesting omission in the 14th game which has never been published in chess literature. I would like to share this omission with my readers:

I must say that not all of his former students showed a respectful attitude towards the Patriarch during the last years of his life. In general, Botvinnik made the impression of a severe and offish person, but people who knew him well could confirm that at heart he was kind and did not shun joking.

And although many years have passed since Mikhail Moiseevich left us, I still remember our last meeting on a rainy Moscow day when walking along the Gogol Boulevard. I saw a familiar figure briskly pacing forward and asked:

"How is your health, Mikhail Moiseevich?"

"It's all right, only sight fails."