Clash of Champions: Karpov vs. Korchnoi

After Bobby Fischer won the world championship in 1972, he was a hero -- not just in the U.S., but for chess players everywhere. But being a hero is not for everyone.

Always hard-working and ambitious, Fischer had fought more against himself than against others, pushing himself to be even better.

But having achieved the highest success possible in chess, he proved that his battle had been absolutely pure and true: it was not the trappings of success he had wanted (as is the case of so many) -- money, fame, respect. He rejected all those things. It was the victory itself.

The problem was, having nothing more to strive for, Fischer could not settle down and enjoy those "trappings" which he never cared about. And this crashed his life.

Since the last game of the match with Spassky, Fischer did not play a single competitive game. Meanwhile, Anatoly Karpov emerged as his challenger.

Karpov was born in 1951 in Zlatoust, a town in the Ural Mountains in the former Soviet Union. Karpov had a very smooth and fast development as a chess player, with a brilliant and balanced style, great mental composure, and high ambitions.

In a way, you can see in Karpov the model of young chess professionals today -- without the computers, of course. Although Fischer had approached chess with a professionalism that had not been seen before -- including physical training and a great emphasis on opening work -- he did so alone and eccentrically in his lonely Brooklyn apartment.

Karpov worked with professional trainers and attended Botvinnik's prestigious chess school. It shouldn't take anything away from his achievements as one of the greatest players ever -- but Karpov was clearly groomed for his work.

In the early 1970s, the young Karpov rapidly went from a strong grandmaster to one of the top players in the world. Unlike Boris Spassky's and Fischer's meandering paths to the world championship, Karpov immediately qualified to the candidates matches for the 1975 world championship cycle by tying with Viktor Korchnoi for first in the Leningrad Interzonal.

Karpov then won matches against Lev Polugaevsky, Boris Spassky and Korchnoi to challenge Fischer.

Fischer made several demands for the 1975 match -- and players and commentators have varied in their opinions on whether these demands were reasonable. He asked that the match be to the first to win ten games, which was unanimously accepted.

But he also asked that he should retain the title in the event of a 9-9 tie -- which meant that Karpov would have to win 10-8. Many people considered this rule to be unfair, and ultimately this demand was what doomed the match.

It is easy to forget that, despite the public's superhero-like image of Fischer, he was a human being with human vulnerabilities and worries. Having won the title, Fischer could no longer gain anything -- he could only lose. The aura of his greatness was in danger. And he was faced by a real chess assassin in Karpov. Fischer knew that few world champions in the history of chess have managed to defend their title against the best challengers.

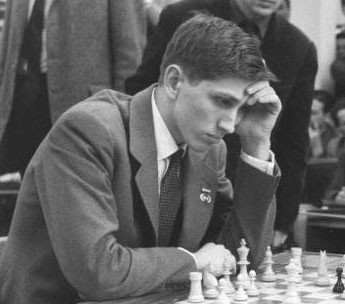

Fischer via wikipedia

Botvinnik did it only with the help of tied matches and automatic rematches. None of his vanquishers had managed to keep their titles. In the earlier years, the champions kept their position by avoiding their top competitors. The sitting champion had a big psychological disadvantage.

It was not so much fear and weakness as a rational calculation that led Fischer to abdicate the throne. First of all, he could no longer gain -- he could only lose. This changed the arithmetic of his match with Karpov. When you add that, for Fischer, his legacy and his position as a mythical figure was more important than any kind of financial considerations or his quality of life, you would come to the same decision as he did.

By refusing to defend the title and disappearing, he defused the pressure on him -- pressure he no saw a reason to deal with, since he had already battled so much, and achieved what he sought.

So Fischer resigned his title and began to live anonymously, in shabby motels and rented rooms in California. It was 20 years until he would play chess again publicly, when he played a rematch against Spassky in Sveti Stefan, Yugoslavia.

Karpov became the champion by default, which meant that his candidates final match with Korchnoi became, in effect, the world championship match. The late '70s and early '80s were dominated by a rivalry between Karpov and Korchnoi. In total they played three matches, with Karpov winning all of them.

via chess.com

Like the match between Fischer and Spassky, the second two Karpov-Korchnoi matches had political overtones.

Korchnoi had defected from the Soviet Union shortly after their candidates match, and even before he defected, there had been friction with chess authorities in the USSR.

The rivalry between Karpov and Korchnoi had an unusual dynamic. Despite Karpov's consistent victories, we can see a revival of the idea of two opposite protagonists. In this case, we have Karpov's pragmatism and composure against Korchnoi's impracticality, creativity and fighting spirit.

Not surprisingly, pragmatism won out. However, a weakness in Karpov's match style came out, and this proved to be decisive when he later faced Garry Kasparov in 1984.

Each of the first two matches with Korchnoi followed exactly the same pattern -- Karpov took a seemingly decisive lead, after which Korchnoi fought back against all expectations, but then Karpov pulled out a victory at the last moment.

This would be seen again when, in 1984, Karpov was ahead 5-0 against Kasparov, but could not win one more game to end the match.

Thus in 1974, Karpov was ahead by three games in the best-of-24 match, but then lost two games before limping to the finish by holding three draws, thus winning by one point.

In their 1978 match, Karpov was ahead 5-2 (this time the match was played until someone won six games, draws not counting) when Korchnoi staged a great comeback, winning three games to tie the match at five apiece. But then Karpov won the last game to win the match.

In 1981, by comparison, Karpov won in very decisive fashion

Throughout their three matches, Karpov and Korchnoi played quite a few tough endgames. First of all, let us see a famous instance where Korchnoi's time pressure problems caused his downfall:

Korchnoi, in typical uncompromising fashion, had grabbed a pawn in the opening and stood better throughout a tough and complicated fight. But now, nearing the end of the first time control, the black pieces had become dangerously active. After 39.g3 (making room for the king) Black can draw in a few ways, such as 39...Nf3+ 40.Kg2 Ne1+ 41.Kh1 Rf6, when 42.h4 Rf1+ 43.Kh2 Nf3+ 44.Rxf3 Rxf3 should be drawn.

But Korchnoi instead played 39.Ra1??, defending the back rank and apparently keeping control of the position without opening the f3-square for the black knight. But now came 39...Nf3+!!, after which he had to resign, since 40.Kh1 Nf2# was mate, as was 40.gxf3 Rg6+ 41.Kh1 Nf2#.

Let us now see the final game from the 1981 match, which was held in Merano, Italy. The basis of Karpov's win in this complex endgame was his advantage in space --here we can see clearly depicted what an advantage it can be to control more of the board.

By winning this game, Karpov won the match and retained the title of world champion. Down 5-2 at this point, Korchnoi was doubtless very dispirited and did not play up to his usual standard.

With this game, his challenge for the world championship ended, but he remains -- along with Paul Keres and Akiba Rubinstein -- one of the greatest players never to win the championship.

RELATED STUDY MATERIAL

- Read the previous article in this series, Clash of Champions: Fischer vs. Spassky.

- Watch GM Roman Dzindzichashvili's Greatest Chess Minds video on Karpov.

- Play the Karpov-Korchnoi match in the Chess Mentor.

- Practice your world-championship-level combinations in the Tactics Trainer.

- Looking for articles with deeper analysis? Try our magazine: The Master's Bulletin.