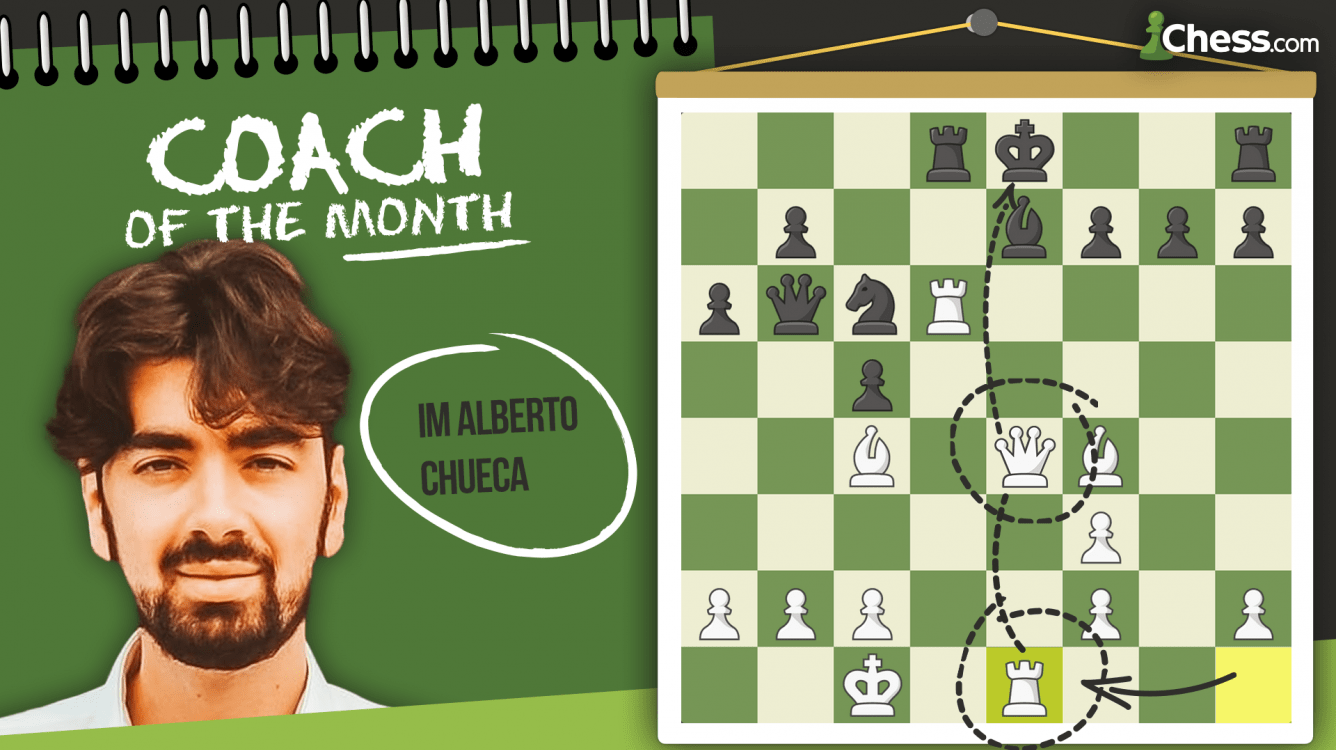

Coach Of The Month: Alberto Chueca Forcen

Chess.com's November Coach of the Month is IM Alberto Chueca Forcen! Chueca is a Spanish international master and the creator of the "Chueca Method."

Chueca is a FIDE trainer with years of coaching experience. With many success stories highlighted on his site, it's clear that Chueca's coaching sessions can help you reach your chess goals.

Readers seeking private instruction can contact Alberto Chueca via his Chess.com profile and can find other skilled coaches at Chess.com/coaches.

At what age were you introduced to chess, and who introduced you?

I remember it vividly. I was six years old, it was a winter afternoon, and my father taught me how to play using some magnetic pieces that we found lying around our house. We had to draw the board on a sheet of paper, and my father barely remembered how to play the game. Later I found out that we hadn't even placed the king and queen properly—but we had a great time, anyway!

It wasn't long until I was taking chess lessons, and not long after that, I played in a tournament in the U-8 [under age eight] category, which I won. This victory motivated me to continue practicing. It wasn't long until I won the U-8 championship in my area and participated in the national championship.

What is your first vivid memory from chess?

My very first tournament will always be special to me. It was a city tournament that happened to be held at my school. It was a U-8 tournament and I was lucky to win it since it was the first tournament I ever played. I couldn't believe it! As a prize, I received a starter book by GM Anatoly Karpov. The experience was magical!

Which coaches were helpful to you in your chess career, and what was the most useful knowledge they imparted to you?

Participating in national championships on a regular basis and with more than 20 years of playing, I've had many coaches. There are around 15 coaches who have helped me, whether on a regular basis or only on a few occasions. Now, with online chess, it is easier to have more regularity. However, it wasn't always this easy to find regular coaches back in the day. Some of them had other jobs and only offered lessons sporadically or for specific periods of time.

Above all, the coach (and friend) who impacted me the most was Daniel Cabrera Moreno (@danekhine on Chess.com). He was key to my progress and helped me improve as a child from a basic level to where I am now. His coaching methodology was based on teaching various important concepts, and he explained them in a very entertaining way. He also knew very well how to interact with children.

The key to a good coach (apart from being a good player) is the ability to impart knowledge, and he excelled at this. Now, as a coach, I apply a similar strategy.

Apart from chess, Cabrera and I shared many hobbies. We have been to Star Wars premieres together from Star Wars I in 1999 to Star Wars IX in 2019. We have maintained a relationship even when I was no longer training. And we also shared games and music in my teens.

He helped me gain a lot of knowledge, develop a training methodology, and passed on to me the passion for playing chess. With all these ingredients it was easy to make progress.

Which game do you consider your "Magnus Opus?"

My favorite game was against a very tough opponent in the last round of a major international tournament. I like it a lot because it clearly shows many basic concepts that I usually explain in my lessons. Sometimes we try to come up with extravagant new plans when many of the "recipes for success" have already been invented and we just need to apply them.

How would you describe your approach to chess coaching?

I would describe it as methodical. Without a doubt, the key to progress in chess is a good methodology. One of the reasons behind the success of my Academy is that students learn concepts adapted to their level. This makes them build a solid foundation and I can say that the vast majority of my students are improving their level considerably.

In the tournaments I play, I can't stop talking to chess players who ask me for advice to train since they don't improve—and some even get worse after spending many hours studying chess. When I ask them what roadmap they have used for their training, many are not able to answer me—they have simply seen chess content. In many of these cases, they have wasted their time and ended up even more disoriented than they were before.

For this reason, after many years of teaching, I have developed a methodology that every chess player can follow, tailored to players depending on their level, which I call The Chueca Method. It explains to the student how much time they need to dedicate to each type of practice, how to best invest their time in each lesson, and what specific concepts they should learn depending on their level. It is a methodology built on many years of teaching experience, and that has helped students win Pan American tournaments, North American tournaments, and the World Youth Championships.

What do you consider your responsibility as a coach and which responsibilities fall on your student?

The success of a coach is measured by how much they can help their students improve. In the chess realm, it could be measured in the successes of the student. Depending on the student's level, it can be measured in rating points, championships won, or simply by their satisfaction and self-improvement. There is truly a multitude of different goals in chess.

The coach has the responsibility of giving the student the necessary tools so they can achieve their goals. Coaches do that by bringing an innovative methodology, motivation, and knowledge to the table.

The student must be clear about his goals and the reason behind investing in their chess. They must know what interests and motivates them to achieve their goals. They must also have the flexibility to know how to learn from their mistakes and from the coach.

The most common mistake I see coaches make is displaying a lack of professionalism (working without passion or exclusively for financial reasons). Many coaches also fail because they teach without a clear plan, improvising as the lessons go.

The most common mistakes students make involve having no real goal or interest in getting better. I've seen many students taking lessons in schools who were just there because they were forced by their parents, something that never proves to be effective.

Students also fail because of a lack of self-criticism. They don't like to admit their mistakes and are not ready to accept what the coach tells them.

What is a piece of advice that you give your students that you think more chess players could benefit from?

To improve as quickly as possible you should study tactics, the middlegame, and endgame technique until you reach an 1800 rating. Invest all your time in it.

Do you know all the ideas behind a knight vs. bishop battle? Do you know all the pawn structures? Can you play with and against hanging pawns? Would you know how to play the Lucena or the Philidor endgame in time pressure without making a mistake?

Only after you can confidently answer all these questions with "yes," should you seriously study openings.

What is your favorite teaching game that users might not have seen?

I like to show this game to my students. The game is not perfect and was not played by top players. However, it demonstrates the importance of following a clear learning methodology. This game demonstrates how a player can benefit from understanding key concepts, like the typical plans of the Isolated Queen's Pawn (IQP):

Here are some of the typical ideas that White could employ:

- Playing moves such as Bd3-c2 and Qd3

- Placing the rooks in the center

- Playing h4-h5 to create tactical threats against e6, g6, and f7

- Playing the thematic sacrifice with Rxe6 (White has many victories in the database winning in 22-26 moves with this sacrifice in similar positions)

What is the puzzle you give students that tells you the most about how they think?

I love endgame technique. So...

What's the result of this endgame?

In the beginning, many students tell me that they know the concept of the opposition as well as its different versions (diagonal or distant opposition). However, when I ask them to play this endgame, they don't know how to proceed.

I have heard many times that Black is winning because he has too many pawns and can deflect the white king. Others think a bit deeper and answer that White is winning because they can capture Black's pawns and Black cannot capture the b3 pawn since the a-pawn would promote.

However, few are able to answer properly. It's a draw because White can capture the kingside pawns but cannot win the two-versus-one endgame since Black is inside of the "box" and can apply the concepts of opposition and distant opposition.

These are basic concepts applied in a complicated position. I know that many students know the meaning of many chess concepts. The way to improve is to gradually increase the complexity of the positions containing these basic concepts. This is how I work with my students.

Do you prefer to teach online or offline? What do you think is different about teaching online?

Definitely online. It has many advantages. Travel is avoided, which, by eliminating many hours in transport, gives a lot of flexibility to both the coach and the student. It is much more comfortable. It is also faster to load problems and check positions with the engine online. This allows the student to learn more concepts in less time.

What do you consider the most valuable training tool that the internet provides?

The ability to load many positions or games in a matter of seconds, making their training session more complete and giving the student more bang for their buck.

Training over the board would cost students a lot more. I remember when I was training (there were no online lessons back then) and we hardly went over certain games or positions. We couldn't set up 30 quick tactic puzzles on the board as it would be very laborious and time-consuming. It would take us longer to set up the positions than to solve the puzzles.

Today you can see more positions or games per hour by instantly loading everything you need with one click.

Which under-appreciated chess book should every chess player read?

To make this answer more fruitful for the readers, I will point out some authors and the areas in which they are specialists:

For beginners, tactics are very important. I would recommend Antonio Gude. I started with his books in 2004 and they have served me well. His books are really instructive and practical. One example is Fundamental Chess Tactics.

To study middlegames, I think GM Jacob Aagaard's books are very entertaining. His books are better suited for slightly more advanced players. Examples include Excelling at Chess or Excelling at Positional Chess.

For endgames, I recommend Dvoretsky's Endgame Manual (as well as any of IM Mark Dvoretsky's book) and 100 Endgames You Must Know: Vital Lessons for Every Chess Player by GM Jesus De La Villa.

Prior Coaches of the Month: