The Greatest Waiting Moves By Grandmasters

Waiting moves are among the hardest to spot in chess because, by definition, they don't seem to have any immediate purpose. They don't overtly change the position in any way and, further, they pass the move to the opponent. That's actually the point in every case: to force a commitment by the other player that you are ready to meet.

I have tried to target all levels of chess players with the examples in each category, logically starting with classic or known examples and ending with games played in recent years. I hope that even titled players can learn something here or use this as reference material. I have divided the expansive and somewhat elusive topic of "waiting moves" into the following categories:

- Zugzwang

- Prophylaxis

- Avoiding Concrete Opening Variations

- Provocation

- Preparing A Veiled Attack

- Walk The Walk: Winning Waiting Moves From My Own Games

One of the rare ways to win a game of chess is to achieve zugzwang. Of course, zugzwang is the magical moment when your waiting move causes the opponent to fall on their own sword. Any move loses for them, and, unless they resign, they are forced to chuck their pieces one by one or to wait for the inexorable end.

The most basic example of such a waiting move can be seen in king-and-pawn endgames. By employing waiting moves, the winning side gains the opposition or an entry into the opponent's position, thereby winning material or decisively supporting a passed pawn. There are certainly easy examples to choose from, but I decided to challenge our readers with an example from the late IM Mark Dvoretsky's renowned Dvoretsky's Endgame Manual.

Black to move and win.

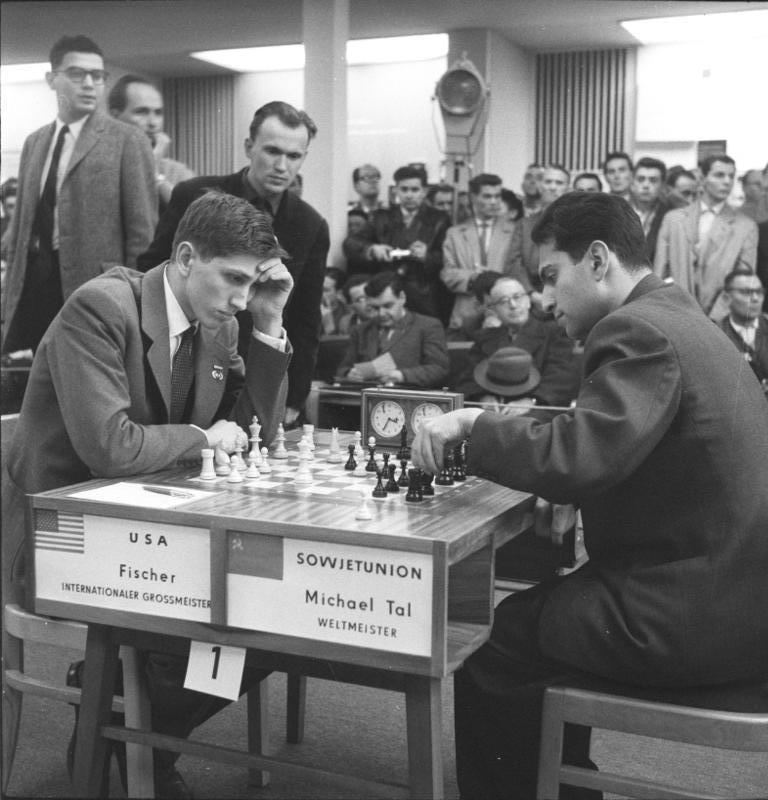

A more sophisticated example, in that it contains more pieces on the board than simply pawns and kings, is the game between GM Bobby Fischer and GM Mark Taimanov in the Candidates Quarterfinal in 1971. This is such a classic example, often the go-to game to teach the ability of the bishop to outmaneuver a knight using zugzwang. Pay attention to the white bishop's sly waiting moves, ultimately leading to zugzwang for the opponent and culminating in an unforgettable sacrifice.

A modern example is a nice game by World Champion Magnus Carlsen in the FIDE World Cup in 2021 where his opponent, GM Vladimir Fedoseev, found himself with absolutely no moves despite having many pieces, including queens, in a middlegame on the board:

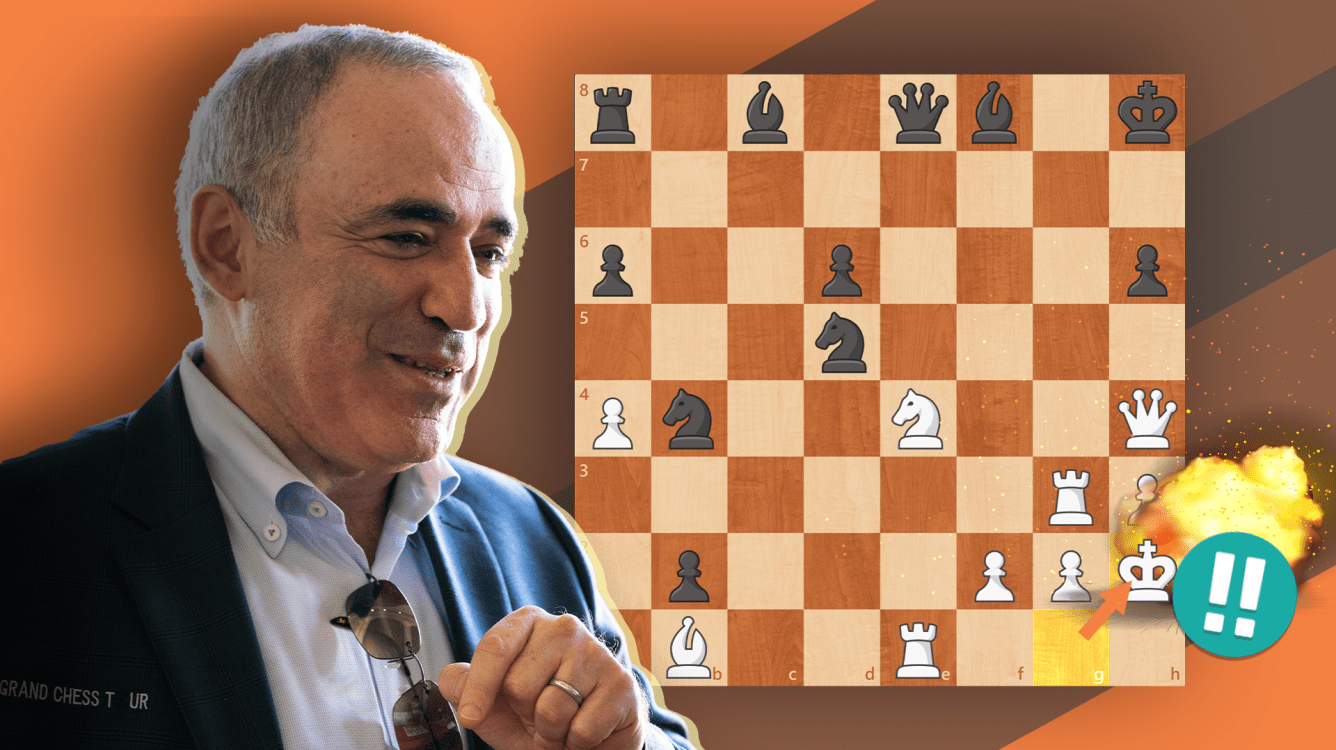

Prophylaxis (think: prophet) refers to moves that safeguard one's own position before any immediate and offensive action. Often, from the side of positional superiority, some waiting moves have to be made to maintain our own king's safety before unleashing damage to the other. The following game is widely known, but an oldie is still a goodie. GM Garry Kasparov's prophylactic king move, exemplifying his acute sense of king safety, takes care of his own before unleashing a tsunami on his opponent's king.

The following, more modern game between GM Nodirbek Abdusattorov and GM Grigoriy Oparin, includes the same prophylactic Kh2. Yes, this is the only blitz game included in the article, but the following moment is instructive and shows how playing a preemptive Kh2 can prepare a deadly attack.

Avoiding Concrete Opening Variations

With the advent of computers, the adventures of the '70s and '80s seem to be over in one respect. There is the impression that the opening has little mystery left as the world's top chess players seem to sit at the computer all day long memorizing all the variations.

However, even this point is proven wrong time and again—a recent example is the game GM Sam Shankland vs. GM Sergey Karjakin in Tata Steel Chess Masters 2022, where the Russian stumbled in a "well-known" line and had to resign on move 26. So much for all that memorization, huh?

Nevertheless, a popular approach at the top level has been using waiting moves to sidestep well-known theory. Through "little moves," as you see below, they introduce subtle differences to already known lines, but these little moves certainly have venom.

The first example is borrowed from GM Alex Yermolinsky's book, The Road to Chess Improvement: 11.h3!? in a Carlsbad structure, arising from the Queen's Gambit Declined. In short, this little waiting move waits for Black's response and helps White determine the optimal setup accordingly.

Two decades later, it's still played—here's a game GM Nodirbek Abdusattorov played just the other week. The following example is chosen because it introduces an idea not mentioned in Yermolinsky's book, published in 1999 (the idea: 14.g4). In addition, although it is not the earliest example in this 14.g4 line, GM Peter Leko is the strongest player to use it against the much younger GM Alexey Sarana.

Another nice example of a waiting move in the opening is 12.Kh1 in the Graf Variation of the Ruy Lopez. While several other moves have been tried with varying success, this tiny side-step is the highest scoring, although it does not have as many games as the other moves. The point, as in the previous example, is that White waits to see what Black's setup will be before committing to action in the center; namely, he waits to see what Black will do with the bishop on c8 and the knight on d7. Although the following game is a draw, former World Champion Vladimir Kramnik's play put former FIDE World Champion GM Ruslan Ponomariov under the gun and demonstrated the danger of this deceptively unsuspecting king move.

Waiting with the purpose of provoking an opponent into overreaching has much less to do with objective evaluation and more to do with psychology. The following examples show how simply waiting can provoke the other side into committing a gruesome mistake.

Now, who could be a stronger provocateur than English GM Tony Miles, who infamously defeated then-reigning World Champion GM Anatoly Karpov in 1980 with the stunning 1...a6.

Okay, now that we've introduced Miles with that little move, let's show an even nicer, more complex move he played in 1989, the mysterious 18...Rac8!?. I had a hard time understanding this on my own and used this article by FM Niranjan Navalgund to comprehend this dumbfounding rook move and to write the annotations.

At the time of writing this article, it is hard to avoid including this recent example by GM Richard Rapport against GM Dmitry Andreikin at the final of the 2022 FIDE Grand Prix in Belgrade. With two minutes on the clock against eight, Rapport declines a threefold repetition simply to keep the game going 30.Qe5!!, which in itself doesn't change the position objectively, and provokes his opponent, who probably expected a draw, into making a mistake almost immediately.

This extraordinary waiting move rewarded Rapport with a tournament victory and, with that, a spot in the Candidates Tournament. FM Carsten Hansen has already provided superb annotations to the game, so I include them below, taken from this article:

Sometimes the purpose of a waiting move is to prepare an unexpected attack, to hide one's intentions. While this next example is perhaps controversial because Fischer's 14...Kh8 has the very concrete idea of clearing the g8-square for the rook, I still include it to expose students of the game to such an original and, when you see it for the first time, shocking plan. I select this game in particular because it is less known than Fischer's win against GM Anderssen with the same plan:

The following game is a much more sophisticated example of the same concept. This one is a truer waiting move, however, as 12.Kh1 does not only prepare the idea of g4. It is more flexible; it takes him a while as he improves his position in the center before committing to the same idea as Fischer with 16.g4.

Winning Waiting Moves From My Own Games

I've included this section to show how these ideas can be applied to chess games at the club level. While they are obviously not as impressive as anything by world-class grandmasters, I think the following examples, played before I even reached the national-master level in the U.S., show that ordinary human beings are also capable of waiting for their way to victory.

In the following example, from a position of absolute domination, my waiting move left White helpless with no moves.

The following game was an important one for me. After butchering an advantage in the middlegame, I desperately squeezed an equal rook endgame up an extra pawn, but my opponent defended well and reached this theoretically drawn endgame. I didn't give up and, ultimately, waiting with f3 before pushing f4 was the idea that won me the game; and with a win in the following game, I won a cash prize in the tournament.

I'd like to thank several people from Chess.com and beyond for helping me find and explain many of the examples you enjoyed above: GM Robert Hess, IM Erik Kislik, FM Niranjan Navalgund, Dylan Rittman, and others. I hope this article helps you expand your arsenal of positional ideas and that you can't wait to use these ideas in your future games!