How Often Is The World Champion The Best Player?

Few would question that, in an ideal world, the best chess player would be the world champion and vice versa. We can agree that GM Magnus Carlsen, who has been world number-one by rating since 2010 and world champion since 2013, is both. But at some point next year, he won't be.

How often is it the case that the best in the world is not the champion of the world? To some degree, the question is subjective. But while no single methodology will be perfect, there is still data to guide us. We use ChessMetrics.com through 2004, FIDE lists since 2005, and all-time Computer Aggregated Precision Scores (CAPS) to answer this question.

We considered only the classical line of champions. The months when there was an ongoing match that eventually changed the titleholder were considered to have no champion. (For example, the 1921 World Championship lasted from March 18 to April 28 and was won by the challenger, so March 1921 and April 1921 were left out of the calculations.)

- Initial Subjective Hypotheses

- The Rating Charts

- The Players: Steinitz | Lasker | Capablanca | Alekhine | Euwe | Botvinnik | Smyslov | Tal | Petrosian | Spassky | Fischer | Karpov | Kasparov | Kramnik | Anand | Carlsen

- The Other Way Around?

- Overall

- Conclusion

Initial Subjective Hypotheses

First, there is this tweet after Carlsen announced he was done:

I would estimate that for something like 30-40% of the history of the World Chess Championship, the official champion has not been the World's strongest player. And in the grand scheme of things it's really not a big deal...

— GM Nigel Davies (@GMNigelDavies) July 20, 2022

When first seeing 30-40 percent, I thought that the estimate was high. The first three champions were the best for most of their time, Jose Raul Capablanca may have stolen some from Alexander Alekhine but not his full time, maybe Alekhine was better than GM Max Euwe but it was only two years, GM Mikhail Botvinnik winning his rematches in 1958 and '61 gave him plenty of cover, GM Bobby Fischer was up there during GM Tigran Petrosian and GM Boris Spassky's time but not necessarily number one, and every one after Fischer retired was the best with some exceptions (GM Garry Kasparov during part of GM Vladimir Kramnik and Carlsen during part of GM Viswanathan Anand). In my brain we are talking about three years here, five years there, but not nearly 30 or 40 percent of the time.

But that's why we don't always trust our subjective minds.

The Rating Charts

Jeff Sonas's ChessMetrics.com system isn't above reproach, but it's very good for what we have historically and is very detailed in its methodology. It stops after 2004, however, at which point this chart uses the official FIDE ratings. The main difference between the two is Chess Metrics takes points away for inactivity, while FIDE ratings hold steady when a player isn't active.

Going monthly, comparing the top player in the rating systems to the world champion title holder looks like this:

| Champ | Flag | Champion | Months Champ | Months Also No. 1 | Percent | Cumulative% |

| 1 | Wilhelm Steinitz | 95 | 49 | 51.6% | 51.6% | |

| 2 | Emanuel Lasker | 321 | 211 | 65.7% | 62.5% | |

| 3 | Jose Capablanca | 76 | 38 | 50.0% | 60.6% | |

| 4 | Alexander Alekhine | 193 | 114 | 59.1% | 60.1% | |

| 5 | Max Euwe | 21 | 12 | 57.1% | 60.1% | |

| 6 | Mikhail Botvinnik | 149 | 35 | 23.5% | 53.7% | |

| 7 | Vasily Smyslov | 10 | 10 | 100.0% | 54.2% | |

| 8 | Mikhail Tal | 10 | 10 | 100.0% | 54.7% | |

| 9 | Tigran Petrosian | 70 | 8 | 11.4% | 51.5% | |

| 10 | Boris Spassky | 37 | 0 | 0.0% | 49.6% | |

| 11 | Bobby Fischer | 31 | 23 | 74.2% | 50.3% | |

| 12 | Anatoly Karpov | 125 | 92 | 73.6% | 52.9% | |

| 13 | Garry Kasparov | 179 | 179 | 100.0% | 59.3% | |

| 14 | Vladimir Kramnik | 82 | 0 | 0.0% | 55.8% | |

| 15 | Viswanathan Anand | 73 | 15 | 20.5% | 54.1% | |

| 16 | Magnus Carlsen | 106 | 106 | 100.0% | 57.2% | |

| - | - | TOTAL | 1578 | 902 | 57.2% | - |

The conclusion: 43 percent of the time the world champion is not the best player, which is outside even Davies' pessimistic range. Before Carlsen took the title, that result is an even higher 46 percent. Let's run through the champions one at a time to see how this has happened.

We will also be aided by CAPS score, which we have data for on a yearly basis instead of monthly. It's important to note that accuracy doesn't tell the complete story: A straightforward draw could see both players play at 95 percent while a complicated mess of a draw might see both players at 70 percent. The difference may be due to stylistic choices by the players rather than their true talent at winning chess games; put another way, playing the most accurate chess may not necessarily be every player's most effective path to victory. And if a player wins a lot anyway, who's to argue with how?

And perhaps to that point, the number in CAPS has been that year's world champion barely one-third of the time. Still, it gives us some extra information.

Steinitz

Wilhelm Steinitz was clearly the best player in the world at the start of his reign in 1886. However, Emanuel Lasker took over that distinction sometime before formally becoming world champion in 1894. Chess Metrics and CAPS both agree that Steinitz began to fall off around 1890. The first world champion was the world's best player for only about half of his time as champion.

Lasker

Lasker's first hiccup comes during 1904-06 when he played below his par at Cambridge Springs 1904 and skipped a lot of time pursuing his Ph.D. Chess Metrics ratings fall in that situation, allowing other players to catch up. Lasker was probably still the best player; he just wasn't proving it. When he began defending his title again, he regained number one for a while.

Akiba Rubinstein took number one during 1912-14, and Capablanca made his first appearance there in 1915 before taking over again in 1919. He was number one for the rest of Lasker's reign. In all, Lasker was the best player for about two-thirds of his title run.

CAPS, which is a huge fan of Capablanca, isn't as thrilled with Lasker. The Cuban star was the most accurate player during 1907-30, eating a shockingly significant chunk of Lasker's reign.

Capablanca

Lasker made a bit of a comeback in the mid-20s, overtaking Capablanca for number one for most of 1924-26. Capablanca got it back before his match with Alekhine but lost that status during their match. In all, exactly half of Capablanca's months as champion saw him at number one.

By accuracy, of course, he was always number one. More than possibly anyone, Capablanca's reputation is built on his accuracy, from even before the time that computers became strong enough to judge human play above reproach.

Whether his accuracy means that you can call him the best during any of those times when his historical rating did not agree is completely subjective.

Alekhine

In Alekhine's first reign, during 1927-35, he was almost always the number one except for a brief few months when Capablanca took it back in 1928. Alekhine's 1937-46 reign was a bit less dominant. Botvinnik hit number one in 1938, and GM Reuben Fine took a few months there as well.

During World War II, just having the opportunity to play was somewhat of an advantage, and Alekhine had that opportunity in Nazi-controlled Germany and France. However, those opportunities eventually declined and by August 1944, Botvinnik had taken Alekhine's spot for good. In all, Alekhine's 59 percent is just above the historical average.

In terms of accuracy, 1933 is Alekhine's only year in the first position. He usually beat you in a mess of complications, not straightforwardly. But he usually beat you.

Euwe

Euwe spent 21 months as champion. Despite often being considered the weakest world champion, he was number one for 12 of those months, exactly in line with the historical average. Euwe's accuracy also competed for the number-one spot during his brief tenure.

Surprisingly, in the other nine months of Euwe's tenure, Alekhine was never number one: Botvinnik for six months and Capablanca's last three months as number one happened instead.

Botvinnik

Botvinnik spent 149 months as world champion and 131 months as the world number one. However, only 35 of his months at number one actually came while he was the world champion. Part of this may be that Botvinnik didn't play a ton of non-title events during his reign. But that's not the whole story.

From June 1950 to December 1952, GMs David Bronstein, Vasily Smyslov, and Samuel Reshevsky traded the number-one spot. Botvinnik then spent just 10 more months as number one before losing his champion title to Smyslov. Botvinnik regained number one while regaining his title and then lost it again almost immediately after the match.

Then Mikhail Tal entered the scene, took number one from Smyslov, and stayed there through the 1960 championship. In fact, Botvinnik was so far behind that beating Tal in the 1961 rematch put Petrosian, not Botvinnik himself, at number one. That endured all the way until Petrosian took Botvinnik out of the world champion position for good in 1963.

Similarly, Botvinnik was the most accurate player during 1942-47 but actually lost that distinction to Smyslov the year he became champ. And by the time the Botvinnik championship era closed, Fischer was already coming in hot with his precision.

Smyslov

Smyslov was the first world champion to stay number one throughout his entire tenure—although his reign was "just" 10 months. The year he won the title, 1957, CAPS prefers the play of Botvinnik, however.

Tal

Tal, like Smyslov, spent 10 months as champion and was world number one for all 10. Unlike Smyslov, Tal is considered by CAPS the most accurate player the year he won the championship in 1960. It is pretty darn impressive that a player like Tal, with his wild sacrificial style, could play so accurately.

Petrosian

Petrosian began his reign as number one, but lost it in February 1964, and never gained it back. Fischer, Tal, GM Viktor Korchnoi, and Spassky traded the pole position instead.

Petrosian was the most accurate player of 1959 but never during his time as champion.

Spassky

Spassky was the first world champion to be number one for none of his reign. Fischer was number one when it started and when it ended, which is true both by rating and by accuracy. Spassky did reach number one for six months during Petrosian's reign, however.

While Spassky was the world champion, the number of months when the champ and the highest-rated player were the same reached a historical low of 49.6 percent. This number has recovered since, as the champions from Fischer through Carlsen have been number one about 70 percent of the time overall. Perhaps this era is what Davies was thinking of.

Fischer

Fischer was, of course, the best player in the world when he won the title on September 1, 1972. Then he didn't play for 20 years. Fischer was so far ahead of everyone else after winning the title that he remained number one until Karpov took it over in August 1974, eight months before becoming world champion on April 1, 1975.

Fischer was the most accurate player in 1972, of course, and then disappeared due to his retirement.

Karpov

Karpov stayed number one until Kasparov popped up in September 1982. Karpov briefly gained number one back when jumping out to a lead in the 1984 World Championship. But Kasparov took it back during the match before it was canceled. In all, though, Karpov was number one for about three-quarters of the time, a historically strong result.

As for accuracy, GM Lev Polugaevsky was surprisingly high and takes several of Karpov's years. One possible interpretation: Karpov's positional sense was so strong he didn't necessarily need to find every best move.

Kasparov

Kasparov was the third world champion to be ranked number one for his entire tenure. Unlike the one-year reigns of Smyslov and Tal, however, Kasparov ruled the chess world for 179 months. By the time Kramnik upset him in October 2000, the all-time identity of the champ and the number one had recovered to 59 percent synchronicity.

Interestingly, CAPS prefers Kramnik to Kasparov during 1998-2000. It's a bit surprising considering how dominant Kasparov was in 1999, especially winning huge tournaments at Wijk aan Zee (including one of the most celebrated games ever), Linares (by 2.5 points!), and Sarajevo.

Kramnik

Kramnik's 8.5-6.5 win over Kasparov in 2000 was not enough to leapfrog into number one. In fact, Kramnik joins Spassky as the only two players to be world number one for none of their championship reigns.

Chess Metrics stops during Kramnik's titleholding period. The last two months, November and December 2004, saw Anand take over number one from Kasparov. But Kasparov was number one on the January 2005 FIDE rating list and stayed there until March 2006, and then he fell off due to a year of inactivity.

At that point, number one went to GM Veselin Topalov, not Kramnik. Anand jumped to number one before winning the title in September 2007. And only then in the following January did Kramnik finally hit number one where he stayed for three months.

Computers like Kramnik more but not so much in sync with his championship period. He had the best CAPS during 2006-09 and, perhaps more impressively, 2017.

Anand

Anand was the best player when he won the title in 2007. He got three title defenses and six years as champion before finally encountering Carlsen who first hit number one in January 2010. He fought with Anand for the spot for about a year before taking number one over for good in June 2011.

By the time Carlsen finally beat Anand for the title, Anand had been number one for only 15 of his 73 months as champion. Carlsen's upcoming post-championship era is getting a lot of attention for obvious reasons, but he probably could have tacked on some time as champion at the beginning as well. Instead, he decided not to play the 2011 Candidates.

2010 is Anand's only year as champion that the computer likes him best.

Carlsen

Like Kasparov, Carlsen has been number one for his entire reign, of which September 2022 is his 106th month. Carlsen would have needed to stay champion and number one for an additional six years before matching Kasparov's total of 179. Instead, Carlsen will settle below 115 before giving his title to the 17th classical world champion.

Carlsen's accuracy apparently dropped somewhat in the 2016-18 period, but that really only drives home the point that it's not necessarily a top indicator of playing strength at the human level, seeing as no one has really argued for anyone else as the best active player for the last decade or so.

The Other Way Around?

What about players who reached number one in Chess Metrics or the FIDE list but never became classical world champions? Spots two through seven might not shock you, but number one probably will. He was helped by peaking during Lasker's first long break.

| Rk | Player | Months | Champ(s) |

| 1 | GM Geza Maroczy | 30 | Lasker |

| 2 | GM Veselin Topalov | 27 | Kramnik/Anand |

| 3 | GM Akiba Rubinstein | 25 | Lasker |

| 4 | GM David Bronstein | 19 | Botvinnik |

| 5 | Harry Pillsbury | 16 | Lasker |

| 6 | GM Samuel Reshevsky | 14 | Alekhine/Botvinnik |

| 7 | GM Reuben Fine | 6 | Alekhine |

| 8 | David Janowsky | 5 | Lasker |

| 9 | GM Viktor Korchnoi | 4 | Petrosian |

| 10 | GM Efim Bogoljubow | 2 | Capablanca |

| 11 | Johannes Zukertort | 1 | n/a |

| 11 | Isidor Gunsberg | 1 | Steinitz |

The number of players who were never world champions but spent at least a year as the most accurate is also 11: Siegbert Tarrasch, Pillsbury, Isaac Kashdan, Reshevsky, Fine, GM Miguel Najdorf, GM Paul Keres, GM Efim Geller, Polugaevsky, and GM Wesley So.

Overall

Overall, there have been 1,578 months with an official world champion (again, excluding those with an ongoing match that moved the title). Of those, the champ has been number one in 902 months, or 57 percent of them. By that count, Davies' estimate is actually low.

And that's with Carlsen going 106-for-106, Kasparov going 179-for-179, and Karpov going 92-for-125. Combined, they were 92 percent compared to 45 percent for every other champion. Going in the other direction isn't as drastic. Petrosian, Spassky, and Kramnik went 8-for-189, just 4 percent, leaving everyone else at 64 percent.

Why would this be? One culprit is lag: The world champion keeps the title throughout the multiyear championship cycle. The next champion may catch up before the match happens (especially as, at least since World War II, you have to play well against strong opponents to get the match in the first place while the champion can wait). This happened to varying degrees in several transitions: Steinitz-Lasker, Lasker-Capablanca, Botvinnik-Tal, Botvinnik-Petrosian, Karpov-Kasparov, and Anand-Carlsen.

Conclusion

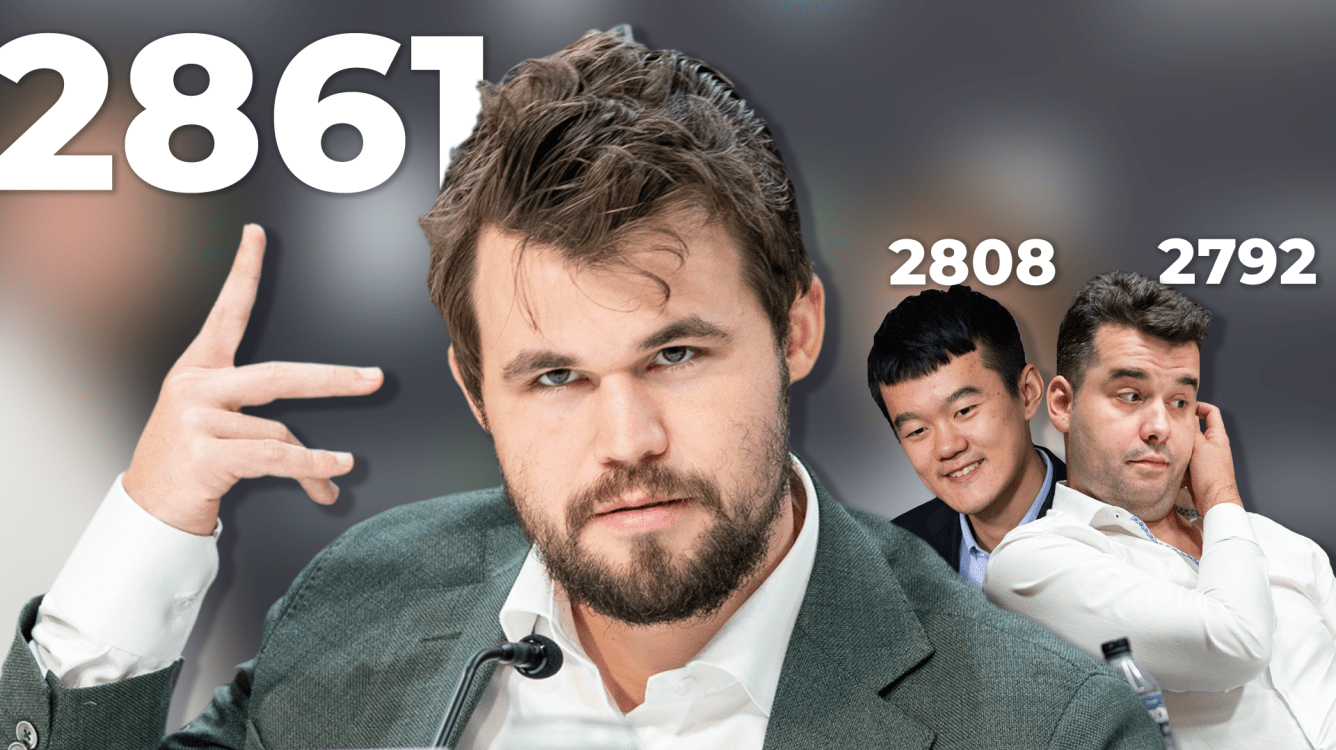

The exact dates of the 2023 World Championship have not yet been set. But as of the September 2022 official FIDE rating list, GM Ding Liren ranks second at 2808 and GM Ian Nepomniachtchi third at 2792. Carlsen, meanwhile, sits at 2861. He is unlikely to be caught in a matter of months, but stranger things have happened. Fortunately, at least the next two best players (as of now) are in line to fight for the championship.

At some point, Carlsen will be neither champion nor at the top of the rating list. Once he officially loses the championship title, it may be years before the number one player and the world champion are the same.

Who will be the next world champion to also have the highest rating? How important are rating and accuracy for you when comparing player strengths? Let us know in the comments!