How To Find The Best Chess Move

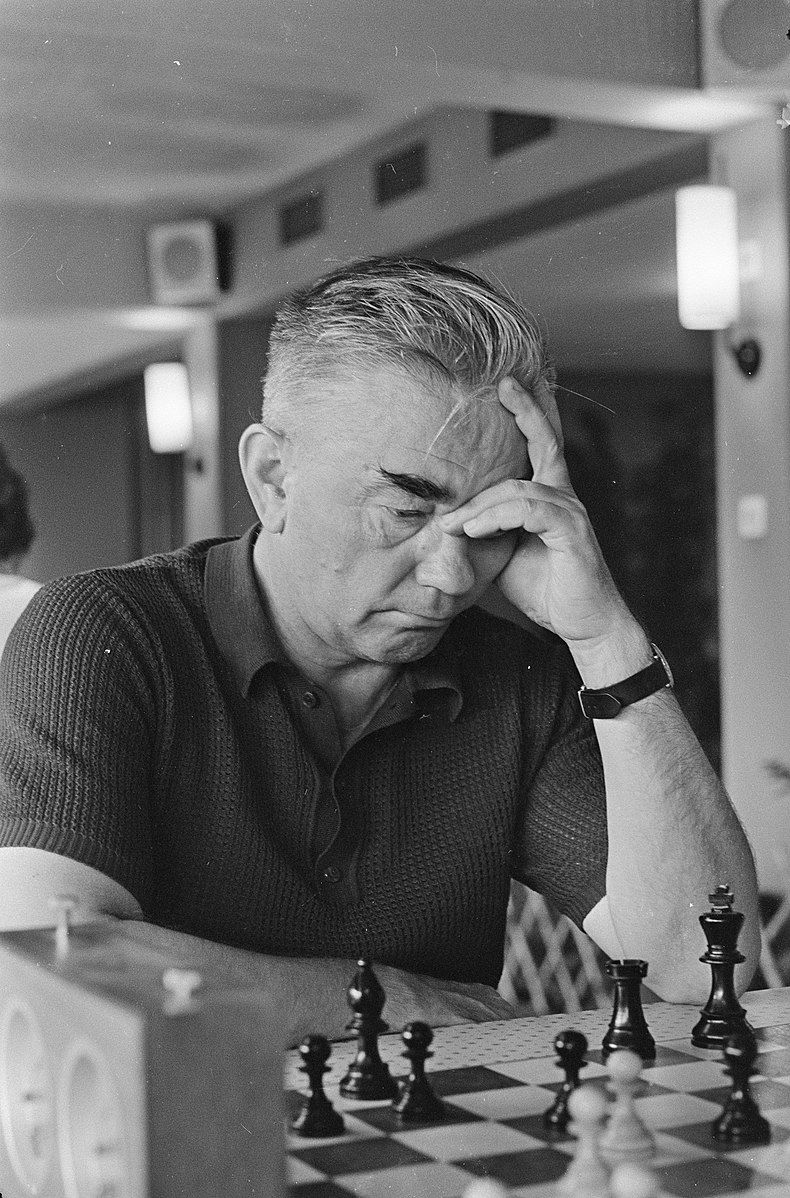

GM Alexander Kotov is one of the most underappreciated figures in chess history. Ask average club players what they know about Kotov and at best they will recall his most famous game versus GM Averbakh.

Personally, I don't think that it was such a great game since in the middlegame Black had a strategically difficult position, and the combination after White's blunder was quite simple and obvious. The fame of this game clearly stems from the famous book about this tournament written by David Bronstein.

Do yourself a favor and get a book of selected games of Kotov. You'll see dozens of truly great games of this talented player.

While there were many players in the history of our game who had similar or even better chess results, it is difficult to find anyone who could compete with Kotov's impact on chess popularity. Thanks to Alexander Kotov, millions of people got interested in chess. The kids of my generation who studied chess seriously would never miss the weekly TV chess school hosted by Kotov. Even the people who didn't play chess at all enjoyed Kotov's book White And Black as well as the movie The White Snow Of Russia, which is based on the book.

As a prolific writer, Kotov wrote many books that became bestsellers. For instance, his two-volume book on Alekhine was sold out almost instantly despite 100,000 copies published. As I mentioned in this article, you would have to pay a hefty premium to get a good chess book in the Soviet Union.

Personally, I used a little trick to read Kotov's books. There was a chain of bookstores called "Friendship" all around the Soviet Union. These shops were selling books printed in the countries of the Eastern Bloc. There I found a bunch of books written by Soviet grandmasters but printed in East Germany. Since I don't speak German, it was challenging at first, but pretty soon I learned the German chess notation as well as some basic phrases like "Schwarz gewinnt." It is funny, but when I just started playing chess, I had more books in German than in Russian!

You are probably wondering why such an extraordinary person as Kotov is not a household name. Well, first of all, he was a household name some 40-50 years ago, but slowly his fame faded away. It might have happened due to the persistent rumors about his collaboration with KGB. Another reason is that the books he wrote about Alekhine were part of the huge Soviet propaganda machine. In order to prove that Alekhine wasn't a nazi and didn't write his notorious articles for Pariser Zeitung, Kotov had to bend some facts.

Nevertheless, we should see the forest for the trees: most of Alexander Kotov's books were very instructive and extremely useful for aspiring chess players.

In my personal opinion, the most important book of his is The Mysteries Of Chess Player's Thinking published in 1970 and one year later translated into English as Think Like A Grandmaster. In this groundbreaking work, Kotov discussed the way chess players search for the best move and how they make their decisions.

Many chess terms that we use today on a regular basis, like "candidate moves" or "the tree of variations" stem from this book. Wikipedia even mentions the so-called "Kotov Syndrome" as "a situation where a player thinks very hard for a long time in a complicated position but does not find a clear path, then, running low on time, quickly makes a poor move, often a blunder".

Let's talk about "Kotov Syndrome" since it is the very first topic covered by the above-mentioned book.

Kotov provides the following position:

He proceeds to describe the thoughts of the master who played White:

"White's attack on the Kingside looks very threatening. [...] "I have to sacrifice," the master told himself, "but which piece?"

Kotov analyzes three promising-looking sacrifices:

Kotov continues: "How many times he jumped from one variation to the other, how often he thought about this and that attempt to win only he can tell. But now time trouble came creeping up and the master decided to "play a safe move" which didn't demand any real analysis: 26. Bc3. Alas, this was almost the worst move he could have played."

Here is how Kotov concludes this story:

"Note in passing that White was wrong to reject 26. Ng4:"

I was very fascinated when I read this compelling story the first time. Still, as an 11-year-old kid I couldn't understand why White decided to resign after he played 26.Bc3. Yes, the position after 28...h4 didn't look too good for White, but it was definitively not the one where you would resign!

Only many years later I learned what really happened in the actual game. Remember I mentioned that sometimes Kotov preferred to bend the facts to make his point? This is exactly the case. Actually, "bending the facts" might be an understatement. It is more like an old Russian joke:

Two friends talk over the phone.

-- Have you heard that Alexey Ivanov won a million dollars in a poker tournament?

-- Well, first of all, it was Nikolay Petrov, not Alexey Ivanov, and he played backgammon, not poker and it was just one hundred, not a million, and it was rubles, not dollars, and he actually lost, not won!

In both Russian and English editions of his book Kotov conveniently omits the names of the players, so here is the actual game for you:

As you can see, White didn't play the moves mentioned by Kotov. Moreover, White didn't lose the game: it was a draw!

By the way, GM Kotov didn't mention a very strong move candidate that White had to consider. In fact, this move essentially wins the game on the spot. I showed this position to my students and all of them rated above USCF 1800 easily found the win. Can you?

Despite the obvious drawbacks, Kotov's book helps you to systematize your thinking. As he explains, first you need to find all the move candidates and only then start analyzing each of them, trying to figure out which one is the best. It is ironic that in the above-mentioned position Kotov didn't follow his own advice and missed the move candidate that would win the game on the spot.

I hope I have managed to whet your appetite, so you'll read this excellent book of GM Kotov.