Kasparov, Nakamura, and Mark Zuckerberg's hoodie

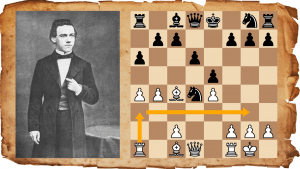

When, in 1995, Garry Kasparov employed the ancient Evans Gambit, I was thrilled - in part because I was a live witness to it, in his game against Jeroen Piket, at the Euwe Memorial tournament. But I was also a tiny bit annoyed, because I realized it was only now that many people would start taking this fascinating gambit seriously.

In fact, I had been playing the Evans Gambit ever since I started to frequent my local chess club (in 1987), and my fellow junior chess mates never tired of making fun of it. “Why don’t you start playing real openings?” “You will never improve if you always play second-rate gambits.” But now, with the World Champion playing it in serious tournament games, I finally had my revenge. Or did I?

Even after Kasparov had scored two crushing victories with it and a couple of quick books on the Evans Gambit had been published, I felt that its popularity wasn’t so much triggered because people really believed in the gambit itself, but simply because the greatest player of all time had played it. Indeed, after Kasparov stopped playing it, the gambit’s popularity also quickly declined again, despite other strong players picking it up for some time and scoring decent results with it. It seemed Kasparov could get away with something most others couldn’t. Kasparov was special – and so he made the Evans Gambit special. But the rest of us was not.

I was reminded of this brief episode in chess history when I recently read an article on the website of The New Yorker about Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO of Facebook, and fact that he often wears rather casual clothes instead of tailor-made suits in public appearances.

The author of the article, Matthew Hutson, writes that this kind of nonconformity – Mark Zuckerberg wearing a ‘hoodie’, Steve Jobs wearing running sneakers – is viewed ‘as a sign of status’ and mentions several scientific experiments to back up this theory. There is even a name for this phenomenon: the ‘red sneakers effect’, after a study on the link between accomplishment and informality.

“The red-sneaker effect fits in with a wider body of research on the idea that certain observable traits or behaviors signal hidden qualities by virtue of their ‘costliness.’ For instance, a peacock’s colorful tail feathers make it easy prey for predators, but they tell a peahen that he’s fit enough to sustain the risk. The more one has of the trait to be touted (fitness, say), the less costly the signal (feathers), making the display of the signal a reliable proxy for the trait. This is how conspicuous consumption works: jewelry is costly, unless you’re rich and won’t miss the cash. Similarly, deliberate nonconformity shows that you can handle some ridicule because you’ve got social capital to burn.”

Of course, I don’t want to suggest that Kasparov (who, by the way, never dressed casually, unlike many of his contemporaries and predecessors) played the Evans Gambit to ‘show that he could handle some ridicule’- but I do think that he was one of the very few people who could get away with such a display of nonconformity. That’s why everybody laughed when I played 4.b4, and everybody cheered when Kasparov did.

Or maybe not. After all, playing the Evans Gambit - an opening that’s been played and analyzed for over 150 years by some of the greatest players in the world, including Bobby Fischer - may not be be such a big display of nonconformity after all – it’s not unlike wearing a hoodie, actually.

Let's not forget the hoodie is probably the number one piece of hipster clothing at the moment – and that's a subculture that I’m sure Mark Zuckerberg doesn’t mind being associated with at all. In fact, it seems to me that dressing like a hipster is a rather uninspired way of showing how nonconformist you are. (A fashionable hoodie can easily cost 500 euros.) Come to think of it, it’s not a sign of nonconformity at all.

So perhaps for some real nonconformity in chess, we need some more extreme examples.

Here’s one that intrigued me at the time:

Morozevich-McShane

Biel, 2004

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.h3

Not good enough? OK, this is what our current World Champion did to Michael Adams a few years ago.

Adams-Carlsen

Khanty Mansiysk, 2010

1.e4 g6 2.d4 Nf6 3.e5 Nh5

At this point, a very strong grandmaster watching the game with me remarked: “This is bullshit, he’s just showing off.” Indeed, despite its originality, it’s hard to believe Carlsen actually liked his position at this point.

If you’re still not convinced, I’m sure the following example will:

Namakura-Volokitin

Lausanne, 2005

1.e4 c5 2.Qh5

Don't forget, Nakamura was already a world class player at the time. Why else would he play this move if not to make a statement of how untouchable he really felt? (He lost that game, but has won with 1.e4 e5 2.Qh5.)

“In the right situation,” Hutson writes, “breaking the rules a little can be a great way to show off—assuming you can back it up.”

Well, forget about breaking the rules ‘a little’. That day, Nakamura wasn’t just wearing a hoodie – he was wearing an old Morbid Angel death metal t-shirt with a dog collar around his neck. Eat that, Mr. Zuckerberg!