Why The Match Of The Century Almost Didn't Happen

Today 50 years ago, on July 1, 1972, the opening ceremony of the world chess championship match between reigning world champion Boris Spassky and his challenger GM Bobby Fischer took place in Reykjavik, Iceland.

Fischer, however, wasn't there, and the first game, scheduled for the next day, was only played 10 days later. The Match of the Century, which captivated the minds of millions of chess fans and which caused a peak in popularity of the game against the backdrop of the Cold War, had a most turbulent run-up.

Fischer was already a star in the chess world, but his resounding victories against GMs Mark Taimanov (6-0), Bent Larsen (6-0), and Tigran Petrosian (6.5-2.5) in the 1971 Candidates matches had made him famous among the non-chess-playing public. Mainstream media were writing regularly about him, and even President Nixon wrote him a letter saying that the country was behind him.

By the end of 1971, a record amount of 15 bids had come in to host the match: from Amsterdam, Athens, Belgrade, Bled, Bogota, Buenos Aires, Chicago, Dortmund, Montreal, Paris, Reykjavik, Rio de Janeiro, Sarajevo, Zagreb, and Zurich. According to GM Max Euwe, the former world champion who was the FIDE President at the time, the highest bids were Belgrade ($152,000 prize fund), Reykjavik ($125,000), and Sarajevo ($120,000), all about 10 times any previous purse for a world title match.

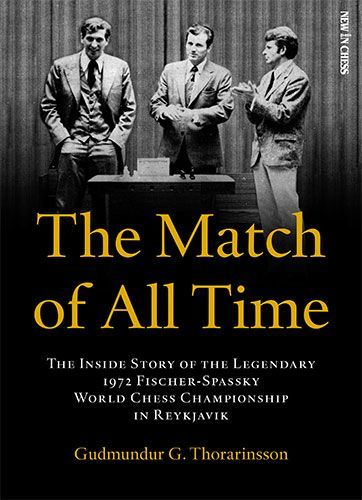

In The Match Of All Time, which was recently translated into English, Gudmundur Thorarinsson, the Icelandic Chess Federation President at the time, wrote that he didn't have much faith in the match coming to Iceland:

"As an example of how little interest I had in the matter, believing our work on the bid to be a total waste of time, I failed to mail the bid to the offices of FIDE on time. I called Freysteinn Thorbergsson and asked him to go to Amsterdam to deliver our bid in person at the FIDE headquarters where the bids would be opened. This he did very competently."

According to Life reporter Brad Darrach, who collected his articles into the brilliant book Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World, Thorarinsson had initially planned on a $25,000 prize fund, but a week before the bidding closed he read a false report in a German chess magazine that Iceland had made a bid of $100,000. Assuming other bidders would try to beat that, he set the offer at $125,000. Thorarinsson makes no mention of this in his own book.

Furthermore, the Reykjavik bid also mentioned that on top of the prize fund, the players would receive 30 percent of the revenue from TV/film rights. Finding himself in fresh territory, 70-year-old Euwe suggested dividing the revenue equally among players, the organizing federations, and FIDE, and sent a telegram to all bidding federations about this. Belgrade was not happy and declared that their bid was now uncertain. Euwe traveled to Belgrade on January 15, 1972, and offered $7,000 to accept their terms if they were to win the bid.

Meanwhile, he had asked both Fischer and Spassky to submit their host city preferences by January 31, 1972. Spassky nominated Reykjavik, Amsterdam, Dortmund, and Paris while Fischer nominated Belgrade, Sarajevo, Buenos Aires, and Montreal.

Given no overlap on the players’ nominations, FIDE gave the players until February 10 to agree on a host city, otherwise Euwe would make the decision himself. Ed Edmondson, the President of the U.S. Chess Federation and long-time manager of Fischer, had traveled to Moscow and had agreed on Reykjavik, under the condition that Fischer would agree.

Euwe was relieved to receive a telegram from Moscow saying the parties had agreed on Reykjavik. However, soon came a telegram from New York: Fischer did not agree! He called Reykjavik too small and primitive, and "a stupid place for the match," a remark that required some band-aid at diplomatic levels. Meanwhile, all this had angered the Russian chess officials, who accused the FIDE President of breaching the regulations—which wouldn't be the last time.

He Sawed The Baby In Half

The highly pragmatic Euwe then came up with a remarkable idea: he asked the two highest bidders to split the match. Belgrade accepted on the condition that they would get the first half, while Reykjavik wanted to secure a reduction of the costs in case the match wouldn't last the full 24 games.

Fischer agreed, and Edmondson said: "Euwe made a Solomonic decision. He sawed the baby in half."

Not everyone liked Euwe's decision. FIDE Secretary H.J. Slavekoorde, who was also the chairman of the FIDE rules committee, resigned from his post in protest. The Russian Chess Federation also protested, noting that Belgrade has a very warm climate in the summer—quite different from what their player was used to—and again accused the FIDE President of breaching regulations. Euwe explained his decisions at an already planned FIDE Bureau meeting on March 2-3 in Moscow. The Russian federation got little support and reluctantly withdrew their protest.

After a 40-hour meeting that started on March 18 in Amsterdam, in which FIDE and the Icelandic and Yugoslav delegations were present, the split-city variant was agreed upon. The new prize fund would be $138,000 (the average of both bids) and a scheme of payments was created for the different amount of games the match could last so that Belgrade would carry the bigger burden in case the match lasted for fewer than 24 games.

Euwe himself could not attend due to a goodwill trip to Australia and East Asia. He learned on March 20 in Sydney that the parties had agreed and a contract was signed by GM Efim Geller on behalf of Spassky and by Edmondson on behalf of Fischer.

Two days later, Fischer once again did not accept Edmondson's signature and demanded from both Belgrade and Reykjavik a change in the conditions, whereby the players should be financially profiting from a potential revenue, and emphasized that otherwise, he wouldn't play. As it turned out, Edmondson did not have the mandate to speak on Fischer's behalf anymore, and the two would soon stop working together.

This time, Euwe stood firm and gave the U.S. Chess Federation a deadline of April 4 to accept the terms of the match. Soon, a telegram came back saying Fischer accepted, and everything seemed in order.

However, by then Belgrade, backed by a Yugoslav bank, had lost its patience and demanded a $35,000 deposit from both the U.S. and Russian chess federations. When the Americans declined, Belgrade pulled out on April 11.

Full Match In Iceland

The Icelandic Chess Federation then offered to host the full match, under the condition that the day of the first game would be postponed from June 22 to July 2, which was accepted. In a match book co-written by GM Jan Timman, Euwe acknowledged that he breached the regulations a little there, which stipulated that the match could not start later than July 1. He felt he had good reasons: Fischer couldn't play on a Saturday anyway due to his religious beliefs, and FIDE had already decided that this July 1 date should probably be removed altogether because it would rule out a lot of cities with a warm climate.

Moscow agreed to a whole match in Reykjavik, the U.S. initially not, but in a second telegram on May 6, it was stated that "Fischer agrees but under protest." Euwe writes that, after the match, he knew what "under protest" meant: "I will play but I will use every opportunity to protest against whom and whatever."

Thorarinsson, in The Match of All Time:

"[That] the World Chess Championship match put Iceland on the map is a generally held view. I firmly believe it was Spassky who put Iceland on the map, as Iceland was his first choice, without his preference we would never have been considered at all."

Fischer's biographer Frank Brady suggested that it was Fischer's Icelandic acquaintance Freysteinn Thorbergsson who convinced him to play in Iceland by pointing out the political significance. A rabid anti-Communist, Thorbergsson had visited Fischer in the U.S. and later wrote in an essay that a Fischer victory would "strike at the uplifted propaganda fists of the Communists."

Those were the days of the Cold War, with the West and the Communists as two separate, dominating ideologies. A chess match with representatives from both sides, being held exactly in the middle of America and Russia couldn't be more symbolic, a point that wasn't missed by the media.

Fischer Makes More Demands

The location of the match was finally decided, but the complications didn't end there. In the last three months before the start, Fischer caused more stir, mostly about the financial arrangements. The prize fund was $125,000 (about $800,000 in today's value) with 62.5 percent going to the winner and 37.5 percent to the loser, besides the aforementioned 30 percent of all television and film rights.

On top of this, Fischer now demanded 30 percent of the sold tickets as well, and said Spassky should also receive part of it. The organizers did not accept this new demand.

We have reached early June 1972, when Fischer was spending time in Santa Monica, California. To get to Iceland, he first needed to get to New York.

On Sunday, June 25, the day Fischer was originally scheduled to arrive in Reykjavik, his good friend IM Anthony Saidy called him and said that he would be flying east on Tuesday to see his father, and he asked if Bobby would like to come along. Fischer agreed, and Saidy would later say that he had a strange feeling that if he hadn't called, Fischer would still be there.

Missing Flights

A few days later, on June 29, Fischer intended to board a flight at John F. Kennedy Airport, and his luggage was already loaded but, as witnessed by hundreds of members of the press who awaited him, he fled the terminal and missed the flight. He would return and spend the next few days at Saidy's parents' house in Douglaston, Queens, chased by reporters there as well.

In Reykjavik, where Spassky had arrived with his entourage on June 21, some two hundred journalists from at least 30 countries were starting to wonder if they had come for nothing. Many of them were "red-eyed from rolling out of bed to meet the 5 a.m. plane from New York" each morning, wrote Darrach. "Not seeing Bobby walk off that DC-8 was getting to be an unpleasant habit."

Around that point, the New York filmmaker Chester Fox, who had the filming rights and was going to make a documentary, was asked by a reporter if he was concerned about the outcome of his investment. Fox replied: "I haven't noticed if I'm concerned. I've been trying too hard not to [soil] my pants."

Euwe himself arrived in Iceland on Saturday, July 1, the day of the opening ceremony. In the morning, Spassky could be seen playing tennis with one of his seconds, IM Iivo Nei, on a court close to the Saga Hotel. When a reporter asked the world champion if he thought his opponent would come, Spassky replied: "No, I don't think Robert James will come."

Meanwhile, in Douglaston, attempts to convince Fischer of playing were made by Edmondson, Saidy, and GM William Lombardy, a talented grandmaster-turned-priest and friend of Fischer's, who would end up joining as Fischer's second.

Opening Ceremony

The opening ceremony was held according to schedule on the evening of July 1 in the 500-seat Icelandic National Theater. Present were the Icelandic President and his wife, ambassadors, FIDE officials, reporters, and other guests. One seat in the front row, however, remained empty.

With Fischer not being present, the chief arbiter of the match GM Lothar Schmid suggested postponing the drawing of colors to the next day. After all, the challenger could be on the overnight flight to arrive for the first game in time...

However, the next day a telegram from Saidy arrived, saying that Fischer couldn't play due to illness. It's important to note that the match regulations allowed for a postponement of up to six days only in case of illness, but a medical examination had to be delivered.

What to do? Await for a copy of the medical examination via telegram? But shouldn't the document come from the match doctor in Iceland, now that the match was underway? But... was it already underway?

These questions were addressed in a meeting with all parties, which Euwe had called for. The arbiter and the Russians argued that a match was underway when it has been opened at the opening ceremony, but Euwe wondered if "speeches and a violin" were enough. The Americans claimed that a match is only underway after a drawing of colors has been performed.

Meanwhile, Fischer himself told the New York Daily News on July 3: "I am not ill. I want my financial demands to be met, otherwise I don't play."

Two-Day Postponement

In another moment of pragmatism, Euwe then suggested a compromise: to postpone the match by two days. The Russians asked for time to deliberate and after lunch they said they weren't enthusiastic but wouldn't protest it. Euwe later wrote: "I did not leave any doubt that in case the Russians wished so, I would disqualify Fischer instantly, but they refused to go into history as The Destroyers of the Match of the Century."

Meanwhile, the Russian press agency TASS attacked the FIDE President, writing: "Euwe is pretending to play a game of chess. Instead of making the decision himself to disqualify Fischer, as the regulations stipulate, he tries to pass the matter onto the shoulders of the world champion."

Euwe is pretending to play a game of chess.

— TASS, Russian Press Agency

Euwe had more talks with all FIDE officials present in Reykjavik and then made the decision official: a postponement for two days, with the drawing of colors now scheduled for July 4 at 11:45 a.m. and the game starting at 5 p.m. The Soviets were furious and filed an official protest after all, and Euwe acknowledged that they were in their right to do so.

Two Important Phone Calls

On July 3, Fischer's solicitor Paul Marshall received a phone call that changed everything.

James Derrick Slater was a successful British investment banker and chess lover who had developed the habit of giving away anonymous prizes to chess events and talented players. After reading about Fischer's financial demands in the newspaper and the match being in danger of collapsing, Slater called Leonard Barden—back then the chess correspondent for the Evening Standard, these days, at 92, still writing for The Guardian— and told him that he wanted to donate $125,000, thus doubling the prize fund to $250,000.

Together with a BBC producer, Barden called Marshall to tell the news, whereupon Marshall wanted to hear it from Slater himself. About 10 minutes later, Slater called to confirm, and agreed with Marshall to deliver the message to Fischer: "Now come out and play, chicken!" Fischer was obviously thrilled when he heard the news.

Whether it was decisive or not is unclear, but there was another famous phone call, on the same day. It was none other than Henry Kissinger, Nixon's national security advisor and future secretary of state, on the line.

His opening sentence is usually cited as "This is the worst chess player in the world calling the best chess player in the world," although Darrach has it starting as "This is one of the two worst chess players..." Kissinger made the point that the match was important for the prestige of the United States and that Fischer should go and play.

That evening, Fischer finally boarded a plane to Reykjavik.

AP footage of Fischer's arrival.

Spassky Snaps

Arriving at 7 a.m. on the morning of July 4 at Keflavik airport, Fischer got a police escort to the Icelandic capital. Upon arrival, he decided that sleep was more important than attending the drawing of colors. He signed a letter that Lombardy would represent him, and closed his bedroom door.

When Lombardy stated that Fischer was too tired to attend the drawing, Spassky snapped. Before, it had been the Russian Chess Federation officials who had protested about all the wrong-doings, but now, finally, the world champion himself had enough. He quickly left the Hotel Esja, but told a reporter: "I still want to play, but I will decide when!"

Soon came an official statement from Spassky (or was it from Moscow?), in which he wrote: "If there now is to be any hope for conducting the match, Fischer must be subjected to just penalty. Only after that I can return to the question of whether it is possible to conduct the match."

If there now is to be any hope for conducting the match, Fischer must be subjected to just penalty.

— Spassky

As it turned out, the "penalty" the Soviets requested was Fischer forfeiting the first game, as Geller told a member of the press, somewhat mysteriously adding that Spassky "wouldn't accept that forfeit." (Little did they know, that a forfeit would happen in this match after all...)

In a meeting with all the parties, the Soviets made three further demands: that Fischer would apologize, that Euwe would condemn the behavior of the challenger, and that Euwe would acknowledge that the two-day postponement violated FIDE regulations.

An emotional Euwe instantly got a piece of paper on which he condemned Fischer's behavior, and admitted that he had violated FIDE regulations and that FIDE regulations and match agreements would be strictly observed in the future. FIDE later telegrammed the Russian Chess Federation that the demand for a forfeit would not be granted.

Greed?

Asking Fischer to apologize was quite something, but he did. He wrote an apology, initially ending with the proposal that the players would give up all prize money and play the match for the sake of chess alone. He wanted to let everyone know he wasn't greedy. In the final version of the letter, that phrase was left out.

While the mainstream media accused Fischer of greed, there were probably other reasons for him to make life so difficult for FIDE, Spassky, and the organizers. One of these reasons might sound strange: fear.

GM Nikolai Krogius, who had written a book about psychology in chess and who was part of Spassky's delegation, wrote: "It is a fact that when you see Fischer at the chessboard, all talk about uncertainty or lack of confidence seems absurd. But before an important contest he appears to be a prey to doubts and vacillation."

GM Larry Evans had a similar view: "Since Bobby has become closer to the top in chess, in his heart a previously uncharacteristic fear of defeat has taken root. In Reykjavik he was able to overcome his fear, only after he sensed that he had upset Spassky's emotional equilibrium."

Another reason was more a principled one. Fischer simply didn't like the idea that others, especially the Icelandic organizers, would make more money on the match than him. He was the star, he was the Muhammad Ali of this match, and he knew it.

Fischer's Apology

In a letter that was delivered to Spassky's hotel room, Fischer apologized for his "disrespectful behavior" of not attending the opening ceremony. "I simply got carried away by my petty dispute over money with the Icelandic chess organizers," he wrote, and also apologized to Euwe and "the thousands of chess fans around the world." Fischer then urged Spassky to not continue demanding the forfeit of the first game.

I simply got carried away by my petty dispute over money with the Icelandic chess organizers.

— Fischer

On the same day, Spassky was called by a high-ranked Soviet official named Sergei Pavlov, who said it was now better for the Russian team to come back to Russia. Spassky, who had consistently refused to join the Communist Party, politely refused.

Spassky appreciated Fischer's letter and said that he couldn't play until Tuesday (July 11) but was eager for the drawing of lots. That drawing of colors eventually took place on Friday evening, July 6, at Laugardalsholl, the playing hall. Fischer arrived 22 minutes late, but it was a relief to anyone present that the American finally showed himself.

Spassky jokingly squeezed Fischer's left bicep, as if they were to play a boxing match, and the result of the drawing was that the world champion would start with the white pieces. While discussing the match regulations, Spassky dropped the demand for the forfeit, and Fischer accepted the request to postpone the first game for a few more days.

Five days later, the match would finally begin. The run-up to the most famous chess battle in history had been a hard-fought battle in itself.