Review: Lisa, Pump Up Your Rating, and other recent books

It’s not easy to find time to read chess books when there’s a World Championship match going on at the same time. Still, chess publishers around the globe managed to reach me over the last few months, and I felt compelled to read some of the most interesting books anyway. So below is an overview of some of the chess books I read recently.

Before looking at these, I want to mention two books I read which are not about chess, but made me think of chess all the time. The first one is Jared Diamond’s The World Until Yesterday, in which the author of the best-selling Guns, Germs and Steel looks at what we (meaning modern Westerners) can learn from traditional societies. Diamond argues that our hunter-gatherer ancestors possessed many useful skills that have now become rare (or even lost), such as speaking multiple languages, detailed knowledge of plants and seeds, and having a much more subtle sense of danger.

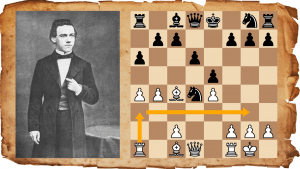

We chess fans can obviously still learn from classic games, but have modern chess players also lost knowledge and skills that the old masters still possessed? Now and then, modern grandmasters dig up some old and forgotten opening variation to try and surprise their opponent – Carlsen playing the Ponziani, Nakamura playing the Muzio Gambit – but what about other areas such as the middlegame or general combinatory vision?

There are examples where modern grandmasters failed to spot tactics that the old masters did manage to find in similar situations. This suggests that perhaps a certain type of ‘crazy’ complications, involving lots of intuitive sacrifices, was easier to play for players who lived more than a century ago than modern top players. An interesting subject to research more deeply, but ultimately I think most skills the old masters possessed have not been lost.

The other book I’d like to mention is Malcolm Gladwell’s new and already-controversial book David and Goliath, in which Gladwell explains how obvious underdogs might still end up on top. Here, too, many parallels with chess can be made - and the author sometimes does so explicitly. Although, like in his previous works, Gladwell writes many things in his new book that are at best questionable and at worst demonstrably wrong, I generally like his style and his trademark of making complicated things look easy, even if it’s sometimes at the cost of accuracy.

A good example is his chapter on a weak girl’s college basketball team which nevertheless became a force to reckon with by adopting an unusual kind of guerilla tactics – by defending full-court-press during the entire game, something that is rarely seen in basketball because it’s so exhaustive. This utterly confused and frustrated their much more experienced opponents who were at a loss how to respond to this high-risk strategy: David defeating Goliath.

I was reminded of another unorthodox (and high-risk) strategy for blind simuls that I discussed years ago with some chess friends. In those days, there was a yearly event in Amsterdam (“Schaken op het Spui”) where a world class player would play a blind simul against 5 players of the same team. We argued that the five players could try and confuse the simul player by adopting a strategy of moving bishops back and forth in a similar but slightly different ways (say, by going Bc8-b7-c8 and Bf8-e7-f8 in alternating order in all five games.)

A very unsual strategy indeed, and some might consider it insulting (a bit like playing full-court-press) but might it not, in fact, work? After move 7 or 8, would the poor simultaneous player still know where all Black’s bishops are, exactly? Would he not run away in despair to the nearest pub? Well, so our theory went, anyway. In chess, as in basketball, there are plenty of ways David can try to defeat Goliath!

In case you were starting to wonder: yes, it’s time to turn to real chess books now – or is it? Two recent novels having chess as their main subject can’t be left unmentioned here.

The first of these is by the Icelandic crime fiction writer Arnaldur Indridason, who’s very popular in The Netherlands but, it appears, a bit less so in English-speaking countries. If you’re a crime book lover, I can highly recommend his novels featuring the enigmatic detectives Marion Briem and Erlendur Sveinsson.

The first of these is by the Icelandic crime fiction writer Arnaldur Indridason, who’s very popular in The Netherlands but, it appears, a bit less so in English-speaking countries. If you’re a crime book lover, I can highly recommend his novels featuring the enigmatic detectives Marion Briem and Erlendur Sveinsson.

When a chess player thinks about Iceland, he immediately thinks about its capital, Reykjavik, and the famous World Championship match that took place there in 1972. Indridason’s most recently translated novel, Twilight Game, is precisely set against the background of this ‘Match of the Century’ between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer. A murder in a cinema theatre in the centre of Reykjavik is the start of a dark plot featuring not only chess and the Americans vs. the Soviets, but also the so-called ‘Cod Wars’, a series of confrontations between England and Iceland about fishing rights in the Atlantic ocean which coincided with the match.

Iceland as described by Indridason in his novels is invariably cold, bleak and full of elusive, taciturn characters. (When I visited the country a few months ago, I was actually struck by the liveliness and open-minded attitude of the people there, but that might have been different forty years ago.) The Fischer-Spassky match plays a prominent role in the plot and acquires some of this melancholy gloom, particularly the 13th match game, won by Fischer - arguably the best game of the match.

As a matter of fact, both Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky are actual characters in Twilight Game. Here’s Fischer’s first appearance:

The door to the men’s shower opened and a tall, meager man in swimming trunks walked out. He had thin arms and a gawky appearance. He said something to the men, who smiled and listened, and walked along the edge of the swimming pool. Then he stretched his arms forward, bent through his knees and plunged in the water.

I’ve tried to search for factual errors in the book, but I couldn’t find them – Indridason clearly did his research well, getting even Fischer’s hotel room number (470) right. After reading Twilight Game, I truly felt a little bit closer to that magical match, which took place a year before I was born. In my opinion it’s a very interesting addition to the existing literature on Fischer-Spassky and therefore highly recommended.

The second novel I want to discuss is GM Jesse Kraai’s debut, called Lisa, A Chess Novel, published last month by Zugzwang [sic] Press. The book is centered around Lisa, a teenage girl from California who is drawn into the world of chess by various characters, notably ‘Grandmaster Ivanov’, a giant eccentric who “talks to his pieces” and speaks English with a Russian accent.

The second novel I want to discuss is GM Jesse Kraai’s debut, called Lisa, A Chess Novel, published last month by Zugzwang [sic] Press. The book is centered around Lisa, a teenage girl from California who is drawn into the world of chess by various characters, notably ‘Grandmaster Ivanov’, a giant eccentric who “talks to his pieces” and speaks English with a Russian accent.

Unlike Indridason’s novel, let alone Nabokov’s The Defense or other novels in which chess plays a major role, Lisa, A Chess Novel is a real chess novel, not so much because it is written by a real Grandmaster, but in the sense that it is about real chess – chess as we chess players know it, not some dream or otherwise ‘unrealistic’ version of it – and as such also features actual players, moves and even diagrams.

At times, I found this a bit confusing to be perfectly honest. Was I reading a work of fiction in the traditional sense here, like Anna Karenina or The Goldfinch, or rather a semi-fictional story with moves and diagrams which happened to be fictional? Was it a comical book, a parody, a roman à clef? Did it even matter?

(…) Igor was a legend. For he had escaped. The Soviet authorities allowed him to play in the prestigious Capablanca Memorial in Havana after he beat World Champion Anatoly Karpov in 1979. On the way back, the big Soviet plane had to make an emergency refueling stop in Gander, Newfoundland. And Igor simply walked off.

This, as many readers will recognize, is actually the true story of Igor Vasilyevich Ivanov (1947-2005), who really did beat Karpov in the Soviet Spartakiad, 1979, and really did defect to Canada in 1980 in exactly the way described in Lisa, A Chess Novel. Later, Ivanov moved to the United States and become a chess coach there, until he died of cancer in 2005.

Now, what are we to make of this? Lisa, A Chess Novel seems, in many ways, a tribute to the real Ivanov and the way he regarded chess, and life in general. However, the time in the novel is set after 2005 – i.e. after the real Ivanov had already died. In the end though, all this shouldn’t matter –fiction is fiction and the only things that matters in fiction are the story and its meaning, and how convincing it is in and of itself. My opinion? Some parts of the novel are great – interestingly enough, especially the non-chess related bits:

Every night, Lisa expected the rain’s chanting patter to allow her past the barriers that made the daylight so insensitive and cruel. And she did drop, as if into a well, briefly caressing leathery patches, sandy ridges and sections of lace as she fell. But she wasn’t able to return from these pilgrimages of her soul with anything tangible that she could be proud of. She only found dinky trinkets, false souvenirs of herself. Like the kind of thing she saw on bumper stickers, or tattooed on the unfortunate arm of a young girl. They could hold a sentiment, but never her. And they certainly never encompassed her with the shrouding intimacy of the cold and dark rain.

On the other hand, I found Igor’s Russian ‘accent’ often far from convincing (“Chessplayer need for learn big suffering of insult without mind losing board” sounds funny but is far from how a Russian native speaker would actually phrase this) and I’m still not sure how I feel about the diagrams and the parts where game fragments are described. Judge for yourself:

Igor read from Tal’s notes: ‘11. Kd1? Twenty years ago, a chess commentator would cringe in horror at such a move. At the very beginning of the game, the white king starts out on a journey! . . . White prefers to mask his development plans for the white knight for the moment, keeping the possibility of either going to e2 or f3, and leaving the f1–a6 diagonal open. Losing the right to castle essentially had no meaning since, first of all, his opponent has not developed his pieces sufficiently and, second of all, black’s own king was uncomfortable on e8.

How interesting are such fragments to you? Yes, we chess players can understand what’s going on, and it’s certainly interesting to read about the ideas in Mikhail Tal’s games, but in a novel? Isn’t it terribly distracting from the real story as well? Hmm.

At the end of the day, though, I managed to forget about such internal doubts and simply enjoyed Lisa, A Chess Novel as a vivid, well-written and often very funny description of one chess pilgrim’s progress. I am definitely looking forward to Jesse Kraai’s first non-chess related novel!

Before we come to the end of this already quite lengthy review, I will also discuss two ‘real’ chess books I both enjoyed reading for different reasons.

Firstly, A Cunning Chess Opening Repertoire for White by Graham Burgess, published by Gambit Publications. It’s a classic opening repertoire book, centered around 1.d4 followed by 2.Nf3, but with a couple of good things. First of all, main lines are not avoided at any cost as is the case in many other similar volumes. For example, the Steinitz Variation of the Queen’s Gambit Declined (5.Bf4) is included and analyzed at length. Some choices are very sensible and healthy, such as the Fianchetto (g3) lines against the King’s Indian and Grünfeld Defenses, or the somewhat rare but very sensible delaying of Nb1-c3 in the Tarrasch Defense.

Firstly, A Cunning Chess Opening Repertoire for White by Graham Burgess, published by Gambit Publications. It’s a classic opening repertoire book, centered around 1.d4 followed by 2.Nf3, but with a couple of good things. First of all, main lines are not avoided at any cost as is the case in many other similar volumes. For example, the Steinitz Variation of the Queen’s Gambit Declined (5.Bf4) is included and analyzed at length. Some choices are very sensible and healthy, such as the Fianchetto (g3) lines against the King’s Indian and Grünfeld Defenses, or the somewhat rare but very sensible delaying of Nb1-c3 in the Tarrasch Defense.

I’m less enthusiastic about Burgess’ recommendation of the Torre Attack (3.Bg5) against 1.d4 Nf6 2.Nf3 e6, to avoid anything that looks like a Nimzo, Benoni or Queen’s Indian. The author defends this choice in the Introduction by promising that

[W]e’ll be developing healthily and seeking ways to take the initiative” and then goes on to say that “we’ll follow up with c4 as soon as there is positive reason (generally that means Black playing …d5), and avoid pre-programmed ‘system’ development (…).

Well, I could be wrong but if there’s one opening I’ve always associated with ‘pre-programmed system development’, it’s the Torre Attack where White usually bashes out his moves without looking at what Black does! Burgess’ main line seems to be based on the ‘Poisoned Pawn’ variation 3…c5 4.e3 Qb6 5.Nbd2 which, however, is not at all thoroughly analyzed. After 5…Qxb2 6.Bd3 d5 7.c4 Qc3 8.Bc2 all lines he gives are very short indeed.

For instance, of 8…cxd4 he writes that it’s “untried, but seems logical (compared to the exchange on move 5) since Black has extracted some benefit from the delay” and then doesn’t give any lines at all! For a repertoire that falls or stands with this line, the very least the author could have done is mention White’s best move here – 9.Rc1! – and given some sample lines. Now it’s just ‘good luck, dear reader’. Rather strange if you ask me.

And finally, there’s Axel Smith’s Pump Up Your Rating, published by Quality Chess. Despite its, well, silly title, it’s actually an extremely interesting and thoughtful treatise by the Swedish coach and International Master, who, according to the back cover, “in just two years boosted his rating from 2093 to 2458.”

And finally, there’s Axel Smith’s Pump Up Your Rating, published by Quality Chess. Despite its, well, silly title, it’s actually an extremely interesting and thoughtful treatise by the Swedish coach and International Master, who, according to the back cover, “in just two years boosted his rating from 2093 to 2458.”

Smith begins his book by taking a look at Willy Hendriks’ provoking and much-debated Move First, Think Later (2012), in which Hendriks argues that “there’s nothing but concrete moves; Alexander Kotov’s mechanical variation trees, and other thinking techniques are oversimplifying and of no use at the board. (…) Hendriks uses ‘the best reaction to an attack on the wing is a counterattack in the centre’ as an example of a rule of thumb. (…) A small statistical research is done to prove his opinion: only in 2 of 34 games was the best reaction to 17.g4 a pawn move in the centre (…)”. Smith admits that

I agree with much of his writing, but I think [Hendriks] takes it too far. The rule to ‘open the centre when the opponent attacks on the wing’ is a part of the inner logic of chess. What he doesn’t mention in his statistical research is that the players with White also know this rule! White played 17.g4 only when seeing that it doesn’t allow action in the centre.

Though casually mentioned in the Introduction of his book, Smith’s point is in fact absolutely crucial to the entire debate. He seems to be a very precise thinker and gives very clear examples throughout his book. Each of the book’s chapters features a theme (for example on exchanging, calculation, and how to analyze your own games) and a ‘model player’ (Ulf Andersson for exchanges, Hans Tikkanen for calculation). By showing concrete examples, Smith mostly offers his student ‘tools’, or ‘thinking techniques’ to improve their skills.

For example, here’s what he writes in the chapter on ‘Calculation’:

Many years ago I had a friend who enthusiastically said that he had discovered the secret to playing well. He said that moves simply came to him when he looked at the board. I didn’t give much for his insight, and rather saw it as a sign of his usual laziness, chatting as much as thinking. Many years later I appreciate what he said. Moves are automatically popping up when looking at the position. I have not yet met a chess player who has managed to stop moves popping into his head, and it only would be harmful if we did stop them.

The importance of the initial thoughts should not be underestimated. In some way the moves that just ‘pop up’ are random, but at the same time they are probably some of the most forcing moves. They give a feeling for the position, what you should strive for, and probably hints about how much time needs to be spent. Only then is it time to start being a bit more structured.

Many of these ‘thinking tools’ Smith offers are just like that: misleadingly simple, yet profound and useful at the same time. It reminded me of a quote I read in Daniel Dennett’s most recent book, on a similar subject, which stresses the needs for such tools: Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking. (Maybe Smith’s title isn’t so bad after all!) The book's motto is a quote from Bo Dahlbom:

You can't do much carpentry with your bare hands and you can't do much thinking with your bare brain.

I hope the books mentioned in this review will stimulate your brain for many days to come!