What Russia Taught The World About Chess

Written by Alexey Zakharov

In the last hundred or so years, Russia became almost synonymous with chess. The country in its many incarnations—Russian Empire, Soviet Union, and now “just” Russia—produced more grandmasters and world champions than any other, and its players enriched the ancient game immensely.

So, let’s now delve (shallowly, and then, of course, more and more deeply) into what Russia and its predecessor states brought to the world of chess.

- Long, Tongue-Twisting Names

- What Is "Russian" Anyway? On Ethnic Diversity

- Emigres And Ex-Soviets

- Opening And Endgame Theory

- State Support And "Chess To The Masses"

- Mass Education And Women’s Chess

- Systemic Dissemination Of Chess Information

- World Champions

Long, Tongue-Twisting Names

It’s more of a joke entry, of course, but GM Ian Nepomniachtchi, the new challenger to GM Magnus Carlsen, is only the latest in the long, distinguished line of Russian and Soviet players who look like an absolutely insurmountable wall of letters when written in English, such as Roman Dzindzichashvili, Zurab Azmaiparashvili, Elena Fatalibekova, Alexander Konstantinopolsky, Olga Semenova-Tyan-Shanskaya, Alexander Ilyin-Zhenevsky, and Fyodor Dus-Chotimirsky.

As a side note, Nepomniachtchi is now officially the player with the longest surname to be involved in a world championship match, surpassing Jose Raul Capablanca and even GM Rustam Kasimdzhanov. I recently translated an interview with the Russian super grandmaster for the Russian Chess Federation that can be found here.

Only recently, India emerged as Russia's main rival in the tongue-twisting department. GM Viswanathan Anand was first on the scene (I remember an old article in 64 humorously comparing his name with that of Alexey Vyzmanavin), but now, he's joined by many other GMs—Pentala Harikrishna, Sethuraman Panayappan Sethuraman, and Rameshbabu Praggnanandhaa come to mind.

What Is “Russian” Anyway? On Ethnic Diversity

I can already hear the protests: “But about half of the names on your list aren’t Russian! There are two Georgians, and Konstantinopolsky was from Ukraine.” So now let’s get very, very serious.

The Russian Empire, Soviet Union, and Russia (the latter somewhat less so, after former Soviet republics became independent states in 1991) were always large, ethnically diverse, and multicultural countries. The terms “Russian” and “Soviet,” similar to “American,” are umbrella terms that designate national rather than ethnic background. Just a few examples:

GM Akiba Rubinstein, a Jew born in the Kingdom of Poland (then an autonomous part of the Russian Empire, usually known as “Congress Poland” in English), was a “Russian” player until Poland declared its independence.

GM Mikhail Botvinnik, a Jew born in Grand Duchy of Finland (another autonomous part of the Russian Empire), was a “Soviet” and then a “Russian” player.

GM Efim Geller, a Jew born in Ukrainian SSR, represented Russia after the USSR dissolved and won the World Senior Championship as a “Russian.”

IM Rashid Nezhmetdinov, a Tatar, was born in Aktyubinsk (now Aktobe, Kazakhstan) and moved to Kazan only at the age of ten.

GM Tigran Petrosian, an Armenian, was born and educated in Tbilisi (now the capital of Georgia, then the capital of the entire Transcaucasian SFSR that included Georgian, Armenian, and Azerbaijan Soviet Republics), but then moved to Moscow and lived there until his untimely death.

Even GM Garry Kasparov—he’s half-Jewish and half-Armenian by descent—was born and raised in Azerbaijan. Then, like Petrosian, he moved to Moscow and went on to represent Russia after the USSR dissolved.

This list might go on and on. As you might see, the questions of ethnicity are a veritable can of worms in every sense of the word. So, for the sake of clarity, the terms “Russian” and “Soviet” will mean strictly “a person who was born in the Russian Empire/Soviet Union/Russia and/or represented the country as a chess player.”

Emigres And Ex-Soviets

Expanding on the previous theme: Do you know that the 1948 World Championship tournament was technically contested by GM Max Euwe and four "Russians?"

Yes, four, that’s no mistake. Botvinnik and GM Vasily Smyslov obviously represented the Soviet Union. GM Paul Keres also played for the Soviet Union, but he started his chess career as an Estonian (nevertheless, he was born in the Russian Empire—even in, should I say, “Russia proper,” since Narva in 1916 was a part of Petrograd Governorate, not the Governorate of Estonia).

But GM Samuel Reshevsky, the only U.S. representative after GM Reuben Fine withdrew, was also born in the Russian Empire! The Kingdom of Poland, as we remember from earlier, was a part of Russia until 1915, and little "Szmul Rzeszewski" was born there in 1911.

Reshevsky and his slightly older compatriot, Mojsze Mendel Najdorf, better known to everyone as GM Miguel Najdorf, of course, can’t really be considered “Russian" players in any sense of the word, since Poland was already independent when they started learning chess. But there are quite a few players who started their careers in Russia or the Soviet Union and then emigrated to the West for various reasons.

Vera Menchik (1906-1944)

The first women's world champion was Russian-born. Menchik's father was Czech, and her mother was an English woman; she was born and went to school in Moscow, even winning a youth tournament there. Her family emigrated from Soviet Russia in 1921 and settled in England. She won the 1927 Women's World Championship and held the title until her untimely death in 1944.

Menchik was the first woman to play regularly in high-level men's tournaments and occasionally even beat grandmasters such as Euwe! She was a true role model for chess-playing women all around the world.

Alexander Alekhine (1892-1946)

Alekhine also won the world title in 1927, already being a naturalized French citizen. His relationship with the USSR soured soon, after he gave an anti-Bolshevik speech at a celebration in Paris and was quickly declared a "renegade." Still, he was born in the Russian Empire, learned chess there, and even won the All-Russian Chess Olympiad in 1920 (later recognized as the first USSR championship) before marrying a Swiss woman and emigrating to the West.

After Alekhine's death, he was posthumously welcomed "back to the fold" and praised as a direct link before the old Russian school of Chigorin and the new Soviet school.

Efim Bogoljubov (1889-1952)

Bogoljubov was another early Soviet champion who was later declared a "renegade." Born in the southwestern part of the Russian Empire in what is now Ukraine, Bogoljubov got his chess education in Kiev. In 1914, he was interned in Mannheim (together with Alekhine and several other Russian players) and ultimately settled in Germany.

Ten years later, he briefly returned to the Soviet Union, and arguably had his career peak, winning the 1924 and 1925 Soviet championships and the famous 1925 Moscow International. Unfortunately, Bogoljubov was barred from entry into several countries because of his Soviet passport and decided to renounce his citizenship so that he could have a wider choice of tournaments to play. The Soviet officials, unsurprisingly, took major offense, and Bogoljubov became essentially a non-person in the USSR until his death.

He played two world championship matches with Alekhine, losing both.

Viktor Korchnoi (1931-2016)

The man. The myth. The legend. Viktor the Terrible, "the villain," "the candidate" (during the first Karpov-Korchnoi match in 1978, the Soviet newspapers avoided his name like the plague, only calling him "the candidate" in the match reports), the ultimate heel player, if you excuse me for a bit for the use of pro wrestling terminology.

Korchnoi won four Soviet championships (only Botvinnik and GM Mikhail Tal have more Soviet championship wins, tied with six) and had a very distinguished record playing for the USSR team. He was very disgruntled when chess officials openly preferred Karpov over him in the 1974 Candidates' cycle (ostensibly because Korchnoi, unlike Karpov, was a "defeatist" who said there was no way to beat GM Bobby Fischer) and made some very unfavorable remarks in the press. The powers that be made his life hell.

After defecting in 1976, Korchnoi had an equally long and distinguished career in the West. His longevity was incredible—who else but Korchnoi could beat both Carlsen and GM Fabiano Caruana and still make FIDE top 100 in his 70s?

David Janowsky (1868-1927)

The first Russian-born emigre player to take part in a world championship match (the first Russian one was Mikhail Chigorin), Janowsky was utterly crushed by Emanuel Lasker, but, as they say, it's the thought that counts. Despite living outside of the Russian Empire for most of his life, he did take part in the 1902 Russian championship, finishing behind Chigorin and Schiffers.

In some aspects, Janowsky was a predecessor of two very dissimilar players: Tal (highly inventive, attacking, not-always-sound play) and Korchnoi (he had an even worse heel attitude, calling most of his opponents "patzers whom he could easily give knight odds"). I think that had Janowsky lived today, he would've been a very entertaining streamer.

Akiba Rubinstein (1880-1961)

The candidate for a world championship match that was not to be, Rubinstein was one of the strongest chess players in the early 1910s, showing very impressive results, but unexpectedly faltered in St. Petersburg 1914, not even making the top five. Nevertheless, a world championship match between him and Lasker was arranged for the later part of 1914 but never took place because of the war.

Even though Rubinstein never got to challenge for the title, he still won many tournaments and advanced chess immensely with his contribution both to opening and endgame theory. Sadly, mental illness made his playing more and more inconsistent and forced him to ultimately retire in the early 1930s.

Aron Nimzowitsch (1886-1935)

My System. Need we say more?

One of the most prominent chess theoreticians of all time, Nimzowitsch, like Rubinstein and Janowsky, was a Russian Empire-born Jewish player. He competed in just two internal Russian events, the 1912 and 1914 editions of the All-Russian Masters' Tournaments. The latter was tied with Alekhine, and after drawing a playoff match, they were both admitted to the 1914 St. Petersburg international tournament.

After escaping the crumbling Russian Empire in 1917, Nimzowitsch ultimately settled in Denmark. There he wrote his magnum opus, My System, and Chess Praxis, which basically became the chess player's bible for the next half century. His career peaked in the late 1920s, but, again like Rubinstein, Nimzowitsch didn't get to challenge for the world championship because (unlike Bogoljubov) he couldn't secure funding that satisfied Alekhine.

Savielly Tartakower (1887-1956)

Another hugely influential theoretician of the 1920s, the author of The Hypermodern Chess Game, almost as legendary as My System. While born and receiving primary education in the Russian Empire, Tartakower was never a Russian citizen and even fought for the Austrian army at the Russian front in World War I. Nevertheless, he knew the language well enough to translate Russian poets into various European languages and even write some poetry himself.

In addition to his contributions to chess theory (the popular Catalan Opening was his invention), Tartakower was known for his wry humor. His "Tartakowerisms," such as "The winner of the game is the player who makes the next-to-last mistake," are still fondly remembered in the chess world.

Ossip Bernstein (1882-1962)

At the age of 72, a Russian-born emigre grandmaster played first board at a Chess Olympiad. Are we talking about Viktor Korchnoi, or...?

Unlike Rubinstein, Nimzowitsch, and Tartakower, Ossip Bernstein was never in the world championship picture and didn't contribute to chess theory as much as them. Still, like Rubinstein and Tartakower, Bernstein is a member of the exclusive Chigorin Club—he defeated a reigning world champion in a classical tournament game.

Fedir Bohatyrchuk (1892-1984)

Another "non-person" of Soviet chess, Bohatyrchuk's name was struck out of almost every chess reference book, only appearing in tournament crosstables. The reason for this was simple enough for the Soviet authorities: during World War II, Bohatyrchuk worked as a radiologist under the Nazi occupation of Ukraine, later signed the Prague Manifesto, and joined Vlasov's Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia, which was, for them, tantamount to treason.

Bohatyrchuk was a part of the group of Russian chess players interned in Germany in 1914, together with Alekhine, Bogoljubov, and Romanovsky. With the latter, he won the 1927 USSR Championship; much later, in the 1950s, this fact precluded Romanovsky from being awarded the international grandmaster title: part of the Soviet federation's claim was Romanovsky's 1927 title, but when FIDE reminded them that Bohatyrchuk would also receive the grandmaster title on the same grounds, the USSR withdrew their claim.

Bohatyrchuk was a true nemesis for the young Botvinnik—the future world champion never managed to defeat the Ukrainian doctor, and his overall score against Bohatyrchuk was +0-3=2.

Bohatyrchuk's third and final win against Botvinnik, which apparently caused him some trouble with the authorities.

Curiously, Bohatyrchuk played in the same 1954 Chess Olympiad as Bernstein, taking fourth board for Canada.

Quite a few ex-Soviet players settled in the United States after emigration. The following four, two men and two women, are arguably the most famous of them.

Boris Gulko (b. 1947) and Anna Akhsharumova (b. 1957)

This unique chess-playing couple holds the distinction of being the only two people who won both the USSR and U.S. chess championships. Gulko won one Soviet championship (in 1977, together with Dorfman) and two U.S. ones (1994 and 1999), and Akhsharumova won two Soviet women's championships (in 1976 and 1984) and one in the U.S. (1987, with a perfect 9/9 score).

Their troubles in the Soviet Union began after they refused to sign a letter condemning Korchnoi in 1977, and this was only exacerbated when they tried to leave the country altogether and settle in Israel in 1979. Both Gulko and Akhsharumova were fully banned from chess for two years and then barred from competing abroad until 1986 when they were finally allowed to emigrate.

Like Bohatyrchuk for Botvinnik, Gulko was an "older nemesis" for Kasparov himself. He was also on a 3-0 score against Garry until finally losing to him in 1995.

Here, Kasparov crumbled in just 24 moves with the white pieces:

Elena Donaldson-Akhmilovskaya (1957-2012)

Elena Akhmilovskaya was one of the successful Soviet women chess players, becoming the first WGM on the Asian continent (she lived in Krasnoyarsk) and even playing a Women's World Championship match in 1986, losing to GM Maia Chiburdanidze. Then she abruptly left the country in 1988.

This story almost looks like something out of a James Bond movie or Chess-like musical: a Russian woman secretly marries an American man during the Chess Olympiad and then escapes with him. Akhmilovskaya herself insisted that she married IM John Donaldson purely out of love and decided to elope because the story was going to be publicized by the Greek press: Akhmilovskaya still hadn't divorced her husband in the Soviet Union, so she feared that she wouldn't be allowed to leave the country if she returned.

Gata Kamsky (b. 1974)

One of the last wunderkinds of Soviet chess, he won the USSR youth championship at the age of 12. A couple of years later, at his father's insistence, the Kamskys moved to the United States.

Kamsky's rise through the ranks of the early 1990s chess was meteoric. After the chess world was split between FIDE and PCA, he took part in both Candidates' cycles, reaching the finals in both cases. Vishy Anand defeated Kamsky in the PCA final and went on to challenge Kasparov, and in the FIDE world championship match, Kamsky lost to Karpov and then gave up chess for almost 10 years.

Kamsky still performed at a high level after his return, winning four U.S. championships and a number of international tournaments, but never managed to challenge for the world title again.

A curious pinnacle of Soviet chess might have occurred shortly before the country ceased to exist. In the January 1991 FIDE rating list, the entire top 10 consisted of Soviet players. Here’s the list, with the federations the players represented after the dissolution of the USSR.

| Player | Rating | Federation(s) after 1992 |

| Garry Kasparov | 2800 | Russia |

| Anatoly Karpov | 2725 | Russia |

| Boris Gelfand | 2700 | Belarus, Israel |

| Vassily Ivanchuk | 2695 | Ukraine |

| Evgeny Bareev | 2650 | Russia, Canada |

| Mikhail Gurevich | 2650 | Belgium, Turkey |

| Jaan Ehlvest | 2650 | Estonia |

| Leonid Yudasin | 2645 | Israel |

| Valery Salov | 2645 | Russia |

| Alexander Beliavsky | 2640 | Ukraine, Slovenia |

GM Boris Gelfand and GM Vassily Ivanchuk (who now prefers to spell his name Vasyl), the contemporaries of Kamsky and participants of the late 1980s Soviet championships, are still very active in the chess world, as is GM Alexei Shirov, who reached the top 10 slightly later than those two. Unlike them, however, Shirov never got to play in a world championship match (Gelfand lost to Anand in 2012, and Ivanchuk to GM Ruslan Ponomariov in the 2002 knockout edition)—even despite actually qualifying for a match with Kasparov by defeating GM Vladimir Kramnik in 1998.

The younger Soviet-born grandmasters who received their chess education in the independent ex-USSR republics still remain members of the chess elite. Ponomariov and GM Rustam Kasimdzhanov won the 2002 and 2004 FIDE knockout world championships respectively, and GMs Levon Aronian, Shakhriyar Mamedyarov, and Teimour Radjabov are still in the current FIDE top-10.

If the Soviet Union still existed, its top 10 wouldn’t occupy the entire FIDE top-10 but still would look quite formidable indeed.

(I added an asterisk next to Aronian's name below since he’s still listed as representing Armenia in the FIDE rankings.)

| Player | Federation | Rating | Place in Top 100 |

| Ian Nepomniachtchi | Russia | 2792 | 4 |

| Levon Aronian* | Armenia | 2781 | 5 |

| Alexander Grischuk | Russia | 2776 | 7 |

| Shakhriyar Mamedyarov | Azerbaijan | 2770 | 8 |

| Teimour Radjabov | Azerbaijan | 2765 | 10 |

| Sergey Karjakin | Russia | 2757 | 15 |

| Dmitry Andreikin | Russia | 2725 | 24 |

| Nikita Vitiugov | Russia | 2715 | 26 |

| Peter Svidler | Russia | 2714 | 27 |

| Daniil Dubov | Russia | 2710 | 28 |

| Vladislav Artemiev | Russia | 2709 | 30 |

Finally, to bookend this chapter of sorts, let me remind you that the 2020-2021 Candidates Tournament, like the 1948 World Championship, also featured four “Russians,” and not even in the strictly technical sense of the word! GM Anish Giri, as you remember, was born in St. Petersburg to a Nepalese father and Russian mother and played for Russia until the age of 15 before moving to the Netherlands.

Opening And Endgame Theory

The contributions of Russian and Russian-born (see "Emigres" above) to the opening and endgame theory are so enormous that they probably deserve a huge book rather than a small article—just look how many openings and variations bear Russian names—so I'll try to be extremely brief here.

Russian Game (aka Petroff Defense)

The whole country got an opening named after itself, even though it's usually called the "Petroff" in non-Russian sources. Alexander Petrov, the first Russian chess master, developed this opening in the mid-19th century with the Finnish-Russian master Carl Jaenisch.

Mikhail Chigorin, the "founding father of the Russian school of chess," was the first challenger to Steinitz after the latter became the world champion. He couldn't capture the title, but still commanded great respect both in Russia and abroad.

Chigorin worked on many openings, some of which bear his name, such as Chigorin Defense in Queen's Gambit and the popular Chigorin Variation in Ruy Lopez.

Russian statistician Vitaly Gnirenko created the aforementioned Mikhail Chigorin club in his honor—Chigorin was the first player to defeat a reigning world champion in a classical game.

"1. e2-e4 wins the game!"

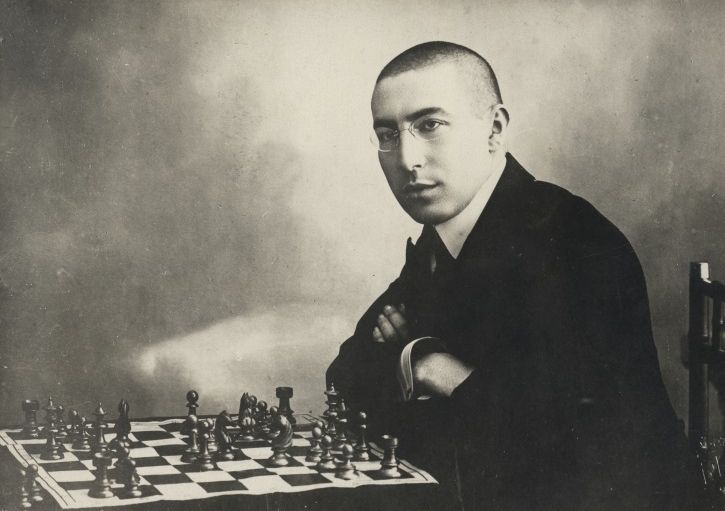

Vsevolod Rauzer

Rauzer, "one of the players whose research lay the foundation for the Soviet chess," as Botvinnik wrote, never achieved particularly great results over the board, but his contributions to chess theory were indeed vast. One of the most popular lines in the Sicilian, Richter-Rauzer attack, is partly named after him.

The fate of Rauzer was sad. He suffered from a mental illness for years, probably at least partially exacerbated by his incredible overexertion (a fellow player remembered him complaining, "Such a pity that I cannot work on chess more than 18 hours a day!"), and was ultimately put into a psychiatric hospital in Leningrad. Soon afterward, the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union, and Rauzer perished during the siege.

The oldest grandmaster still alive, at 99, Averbakh is one of the last living relics of the Soviet era. In his prime, he was a very strong player, winning a USSR championship, but then dedicated himself to coaching and administrative work (he'd been the editor of Shakhmaty v SSSR and a Soviet Chess Federation official for many years) and endgame theory research. His book series on endgame theory were in high demand in the pre-computer era.

Nalimov and Lomonosov Tables

Building upon Averbakh's fundamental work, Russian programmers developed tablebases for all six and seven-piece chess endgames. Evgeny Nalimov, a Russian emigre working for Microsoft at the time, created his famous endgame generator in 1998 and calculated the six-piece tablebases several years later. In 2012, Vladimir Makhnychev and Viktor Zakharov, working on the Moscow State University's supercomputer Lomonosov, did the same for the seven-piece tablebases.

State Support And "Chess To The Masses"

State support of chess

“Alexander Alekhine’s speech was most principled: he said outright that the future existence of chess is only possible if state organizations would take care of it and govern it.”

Peter Romanovsky, Shakhmaty v SSSR, 1957

This may be simply a legend, but this does sound like something Alekhine would have said. In his small book Das Schachleben in Sowjet-Russland (Chess Life in Soviet Russia), published in 1921, Alekhine was very pessimistic about the future of Russian chess, writing that “everything depends solely on the personal influence of some government official or other, similarly to Moscow enjoying a brief chess renaissance solely thanks to Ilyin-Zhenevsky.”

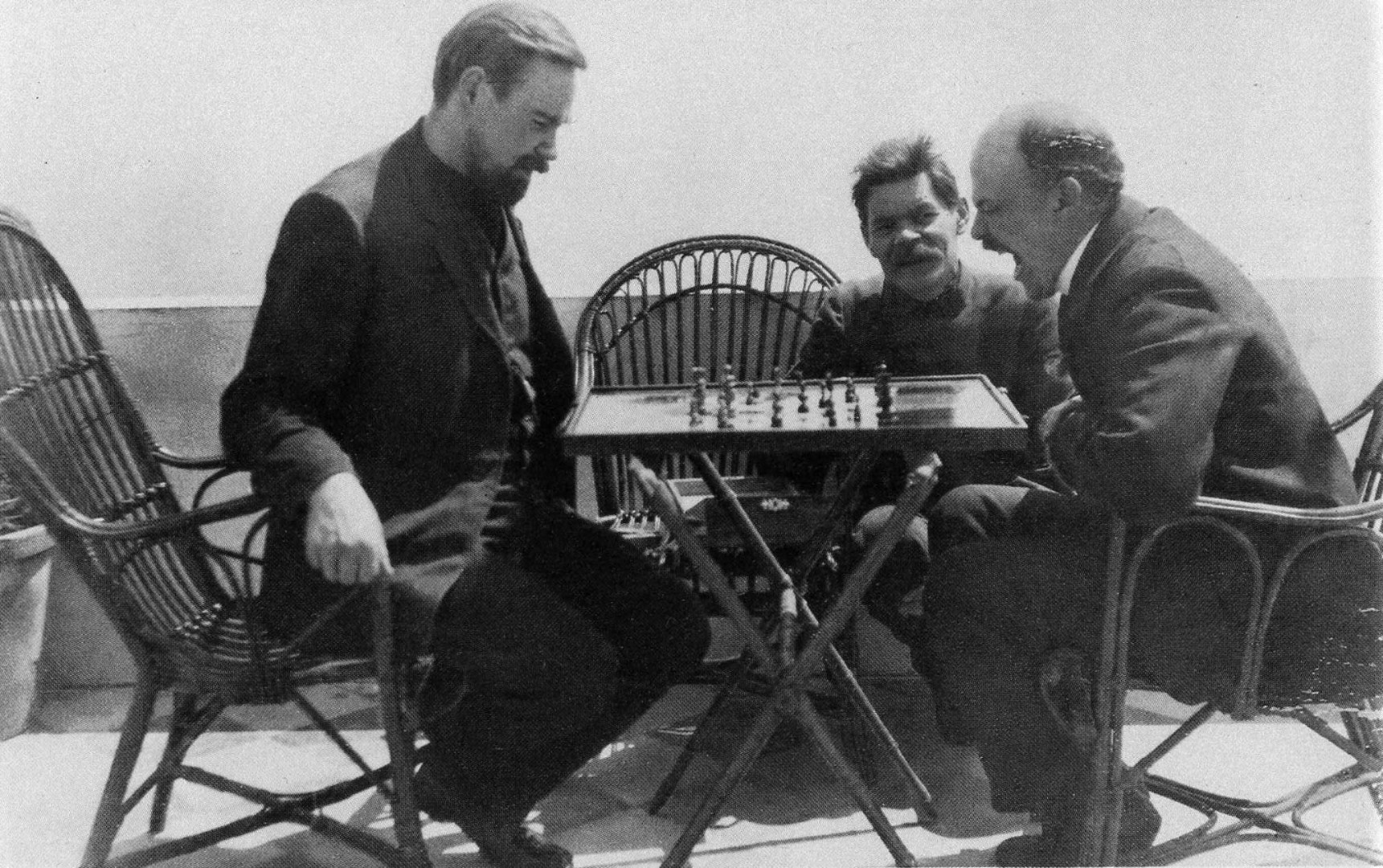

The Soviet state played a huge role in the development of chess. It was perhaps a lucky accident at first: Vladimir Lenin was an amateur chess player who enjoyed an occasional game or problem to solve. (This later allowed Yakov Rokhlin to invent the famous fake quote, “Chess is gymnastics of the mind,” which helped to persuade many a regional leader to offer up funds for chess.)

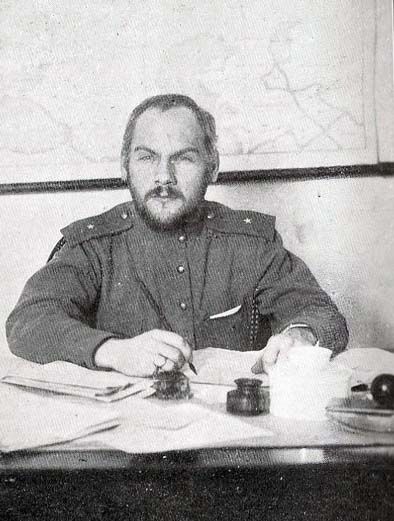

Ilyin-Zhenevsky, a strong master who defeated Capablanca at the 1925 Moscow International, was a brother of Fyodor Raskolnikov, a high-ranking Navy official, and, thanks partly to that, wielded considerable influence as well—that’s what allowed him to organize the “All-Russian Chess Olympiad” of 1920, later recognized as the first USSR championship, and include chess in the Vsevobuch (“Universal Military Education”) program for youth with other, more physical sports.

Soviet Chess as a system supported and controlled by the state was created in the mid-1920s by Nikolai Krylenko, the prosecutor general of the Russian Republic (later known as the People's Commissar for Justice) and the chairman of Chess and Checkers union, who saw chess both as an entertaining intellectual game and as a vehicle for the political education of the masses.

In the Soviet Union, especially then, “political education” obviously meant “promotion of communism” and little else, but his notion that “art workers should also be political workers” almost looks like a rebuttal to modern comments addressed to celebrities—"you should stick to your movies, or music, or football, or whatever, not make political statements.”

Of course, state support for chess has as many drawbacks as it has advantages. Since the 1930s, chess (like other sports) has been a tool for the Soviet government to tout the superiority of socialism over capitalism. Thus, state stipends and other privileges that the leading chess players enjoyed came at a price. In the 1920s, it all started modestly—chess players who took part in national championships got travel and lodging compensations and paid leave from their main jobs. Eventually, however, you could face consequences if you didn’t perform at a certain level.

Even Kasparov had his fair share of state support in his struggle against Karpov. Kasparov was the favorite of Geidar Aliev, the head of the Azerbaijan SSR and future president of independent Azerbaijan. Garry had this to say when asked about state support in a May 2021 Reddit AMA: "The USSR considered chess a way to promote the superiority of the Communist system, and I benefited from that emphasis, as did every Soviet player. We had conditions for training and competition that were unmatched elsewhere. Mostly, though, it was that chess was everywhere and so the top talents were discovered and promoted efficiently. There's talent everywhere, but not opportunity."

Nowadays, chess, while still rather popular, isn’t such a serious business for the Russian government. Gone are the days of direct state sponsorship of players and chess being a question of international prestige. China, on the other hand, has taken a page out of the Soviet playbook, and its chess state support system is now probably the most formidable in the world.

Mass Education And Women’s Chess

When I visit the USSR, it seems to me that every tram conductor plays chess better than me.

Hans Ree

“Chess to the masses”—this was the main slogan of the Soviet chess organization (or “chess movement,” as it was usually referred to in the press) in the 1920s and early 1930s. Chess and Checkers to the Masses was even the official subtitle of the famous 64 magazine back then, and it regularly boasted of thousands, and later tens and hundreds of thousands, chess players registered in the Soviet Union. And this law of big numbers obviously paid off. Hundreds of those “tens of thousands” became masters, and dozens of the thousands became grandmasters.

The magazine 64 regularly published reports of minor tournaments and matches in faraway regions of the Soviet Union, even those contested by amateurs. Can you imagine a modern magazine putting a photo of two chess teams of mineworkers in random suburbs of Vladivostok on the front cover? 64 did, in 1929!

The championship system in USSR was also vast. Most trade unions and voluntary sports societies held their own championships and then competed with each other in various team championships. The recently held FIDE Corporate World Championship was actually similar to the old Trade Union team championships of the Soviet Union, only on a worldwide scale.

Mass chess education, of course, didn’t extend only to men. In 1931, in celebration of International Women’s Day, 64 dedicated an entire issue to women’s chess. Several USSR women’s chess championships had been held at that point, and there were even talks about abolishing “women’s chess” altogether and holding only mixed tournaments with both men and women participating. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

("championess" was the "official" Russian term for the women's champion in the 1930s).

I think that women's tournaments do not benefit their participants and do not help them increase their quality of play. The first downside of such tournaments is that, despite the large number of them (trade union championships, city championships, all-Union championships, etc.), women play against the same opponents over and over again. We already know each other quite well, all the strength and weaknesses of our opponents, and so, our playing in such tournaments is mostly based on subjective moments. In each game, we're adapting our own game to the playing of our opponents.

Olga Morachevskaya, 64, 1931

This quote also sounds weirdly relevant for modern times, even if for a different reason. "Playing against the same opponents over and over again" is a distinct feature of modern elite super tournaments, and it's hard to see how to change that.

On a smaller-scale note, in 1935, a highly publicized match between three chess-playing families was held in Baku. The Ivashin family, which had two girls in its lineup, emerged victoriously.

It surely wasn’t an accident that Soviet women enjoyed the same kind of hegemony in chess as the Soviet men did. After GM Lyudmila Rudenko won the women’s championship tournament in 1950, both champions and challengers for the women’s title represented the Soviet Union until 1991, when Chiburdanidze was dethroned by GM Xie Jun. Perhaps the most incredible achievement (surely unrepeatable in the modern day) belonged to WGM Olga Rubtsova, who won the 1956 women’s world championship at the age of 47 while being a mother of five children and only working on chess part-time.

GM Nona Gaprindashvili and the famous Georgian school ushered in a new, more professional era in women’s chess. Nona became the first woman to earn the grandmaster title, and after losing to Chiburdanidze, became “women’s champion” in another sense of the word—she lobbied for woman players’ rights with FIDE.

Systemic Dissemination Of Chess Information

The main feature of Soviet chess that set it apart from all other chess-playing countries is its systemic dissemination of chess information. The amount of affordable chess literature printed by state publishers in the USSR was simply incredible (though, of course, there were rarities as well—for instance, the press run for Isaac Lipnitsky’s famous Questions of Modern Chess Theory was just 15,000 copies; I was told that Fischer learned Russian specifically to study this book). Novelties used by chess masters spread around the country relatively quickly.

The playing field only started leveling slowly in the 1970s, after the advent of Chess Informant—Kasparov even named a book after this: Opening Revolution in the ‘70s. And then computer databases finally made everyone more or less equal; nowadays anyone can study millions of games by making a couple of mouse clicks. Russian chess players are still immensely strong, but they don’t enjoy the tremendous information advantage of their great predecessors.

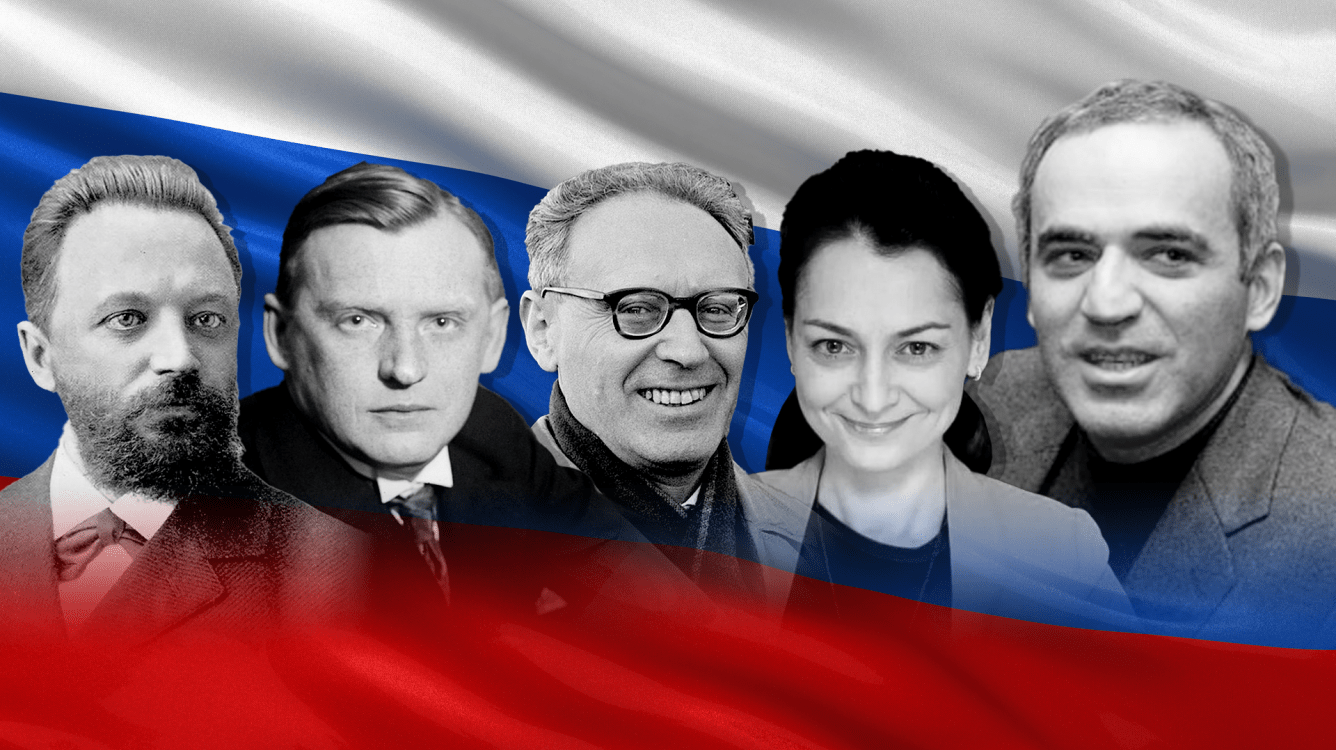

World Champions

Everyone who knows at least a bit about chess knows these names all too well, so I don't think it's necessary to put biographies here. Just look at the gallery and take it in.

Mikhail Botvinnik (1911-1995)

World champion: 1948-1957, 1958-1960, 1961-1963

Vasily Smyslov (1921-2010)

World champion: 1956-1957

Mikhail Tal (1936-1992)

World champion: 1960-1961

Tigran Petrosian (1929-1984)

World champion: 1963-1969

Boris Spassky (b. 1937)

World champion: 1969-1972

Anatoly Karpov (b. 1951)

World champion: 1975-1985

Garry Kasparov (b. 1963)

World champion: 1985-2000

Vladimir Kramnik (b. 1975)

World champion: 2000-2007

Lyudmila Rudenko (1904-1986)

World champion: 1950-1953

Elizaveta Bykova (1913-1989)

World champion: 1953-1956, 1958-1962

Olga Rubtsova (1909-1994)

World champion: 1956-1958

Nona Gaprindashvili (b. 1941)

World champion: 1962-1978

Maia Chiburdanidze (b. 1961)

World champion: 1978-1991

Alexandra Kosteniuk (b. 1984)

World champion: 2008-2010