The (Political) Story Of 'Extraordinary Genius' Sultan Khan

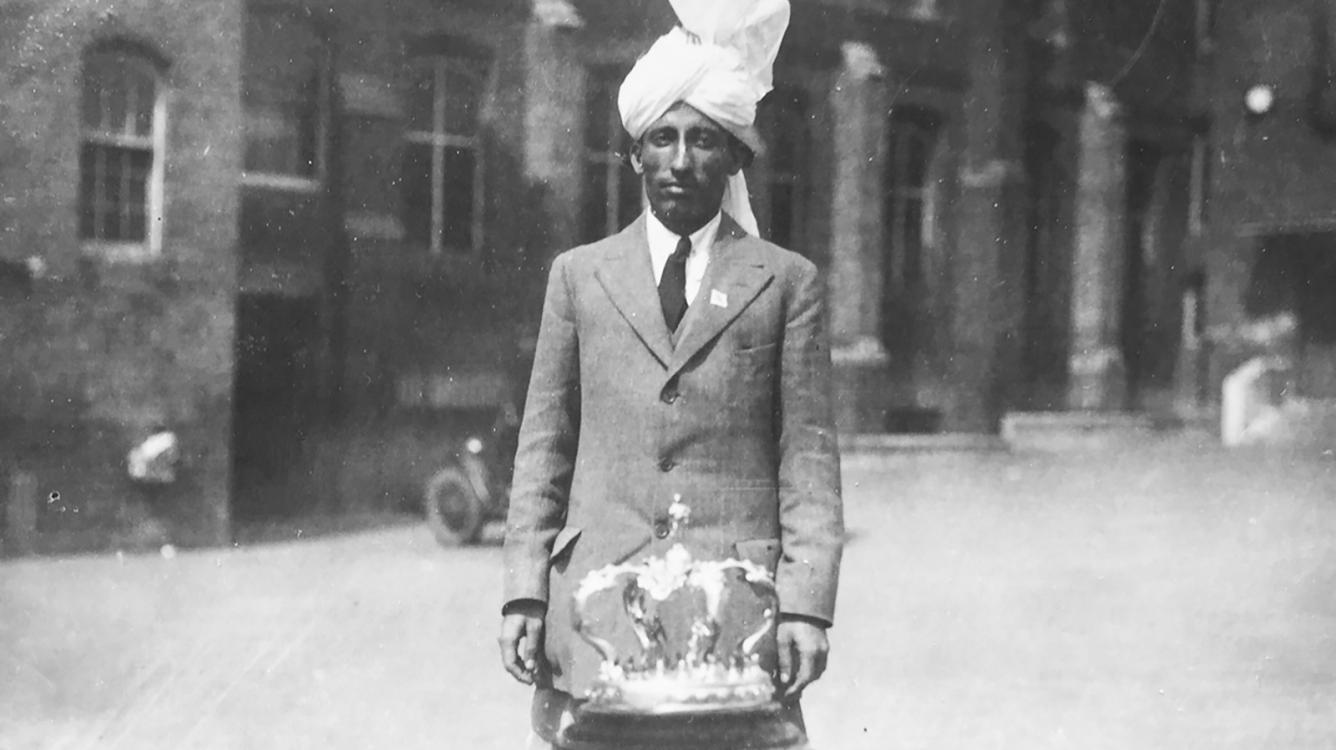

The story of Sultan Khan, a remarkable chess talent from India who was brought to Europe by his master, won the British Championship three times, and defeated Jose Capablanca in a tournament game, is also a political tale. After seven years of research, GM Daniel King has published a biography.

"The fact that even under such conditions he succeeded in becoming a champion reveals a genius for chess which is nothing short of extraordinary," wrote Capablanca years after meeting Sultan Khan at the chessboard. These words perhaps mean even more than the result of their mutual game.

Before we move on, here is that famous game, with annotations as they appear in the book, kindly provided by the author and the publisher. The game was in fact played on December 31, 1930.

Malik Mir Sultan Khan was born in 1905 in Mittha Tawana, Punjab, British India. At the age of nine, he learned to play Indian chess, a version which had different rules for e.g. pawn moves, castling, and stalemate.

Showing a considerable talent for this game, he was considered to be the best player in Punjab when he was taken into the household of Colonel Nawab Malik Sir Umar Hayat Khan Tiwana in 1926.

It was then and there that Sultan Khan learned the rules of western chess and got to play against some of the strongest Indian players. His talent for chess as we know it quickly became apparent as well when Khan won the All-India Championship, organized by Sir Umar, in 1928.

A year later, Sultan Khan joined Sir Umar on a trip to Europe, and in a period of just four years, before returning to India, he scored a number of great successes on the chessboard:

- won the British Championships in 1929, 1932 and 1933

- scored 6/9 in the Hastings 1930-1931 tournament where he beat Capablanca

- defeated Savielly Tartakower 6.5-5.5 in a match in January 1931

- lost a match 2.5-3.5 to Salo Flohr in February 1932

- represented the British Empire in two Olympiads, scoring 11.5/17 on top board in Prague 1931.

It's a remarkable story and one that deserves a full-fledged biography. After R.N. Coles's 1965 limited book "Mir Sultan Khan," the English grandmaster and commentator Danny King has now written a new biography, published by New in Chess, that comes close to being the definitive story.

"Almost seven years ago, I was contacted by a theater director who enjoyed chess and had come across the story," King started. "He got in touch with me and asked me to do some research for him into the story and to kind of explain what was really going on in his chess. So I did a little research for him, and we met up and discussed it. Not much happened after that, but basically I continued my research. I'd always known the story, but I didn't know the background and the details, and the more I looked, the more extraordinary the story became."

On and off over the last seven years, King visited the British Library near King's Cross in the center of London ("the most fantastic building in the world, I love it!" - King) where he did most of his research.

"It was a hobby. And then I thought: I've got all this material, what do I do with it? So I started to organize, and I thought: OK, I think this needs to be a book," he said.

The book is a biography that tells about Sultan Khan's life, the highlights of his chess career, and his games with annotations. At this point, over 200 Sultan Khan games are known, of which dozens never made it into the databases.

King: "The kind of access you get to contemporary newspapers and magazines in the British Library is extraordinary. Some of the stuff is on microfilm, but they also have physical newspapers from 1929, and that's really amazing. I found games he played in simuls, county matches, really obscure stuff.

"When I was doing my research, sometimes I'd spend a couple of days at the British Library, and I'd find nothing. I was sitting in front of these microfilm machines, and at the end of the day, my eyes would be so tired. But on another day, I would suddenly find three new games and a couple of amazing stories. It was like putting together a jigsaw puzzle."

King emphasizes the importance of the political context of the 1920s and 1930s, saying: "The political background is the only way to understand his story. Only if you understand that, can you understand how he came to London and how he disappeared at the end of 1933."

The author continues: "It's bound up with the whole of this turbulent time when the independence movement in India was growing. He came from a very modest background, but he was taken into the household of Sir Umar Hayat Khan. So this is his master, basically. You could say patron, but I think master is kind of more accurate, to be honest.

"Sir Umar was on a political mission to Britain, which was curious in itself. He was fabulously wealthy, he had extensive landholdings in the Punjab where Sultan Khan was from, he was a politician, he was a member of the Indian upper house. So you wonder, why is he interested in securing his position with the British?

He had fought for the British army all over the world actually. So he's very loyal to the British. But actually, he was a Muslim, and he was worried about an independent India because the independence movement in India was increasingly dominated by Hindus. He feared that the Muslim population in India would be marginalized."

"So, Sir Umar went to Britain on a political mission, to represent the Muslim minority (that still consisted of millions) but also to represent the so-called 'martial races.' Basically, these were tribes in northern India that the British had designated as the 'warriors.' Sir Umar was part of one of these tribes and fought with the British and recruited many soldiers for the British. He wanted to stress to the British how important the Muslims were and how they helped secure Britain's place in India.

"When he came to London, he brought Sultan Khan with him. He had already brought him into his household, trained him in western chess since 1926—he hadn't played western chess before—and Sultan Khan was his protege. So this was a kind of soft diplomacy. Sultan Khan made the headlines for him, sort of represented the intellectual side, and his master, Sir Umar, was the warrior. Between the two, they were kind of a perfect combination.

"Sir Umar was a decent player himself. He recognized Sultan Khan's talent and invited some of the best Indian chess players to train him for a couple of years before they came to London. Not that this was training in the kind of strict Soviet sense. They used to play a lot together.

"Sultan Khan joined the household in 1926 and then had training from these Indian players in western chess, and then Sultan Khan won the All Indian Championship in 1928, organized by his master Sir Umar. It was at that time, during this championship, that Sir Umar met a very influential political in Delhi, called Sir John Simon, who was also a keen chess player. That's when, I think, the plan to bring Sultan Khan to London really crystallized.

"As far as I could see, Sultan Khan did not have a political bone in his body. It wasn't his place to offer any opinions, but he was brought—I can't stress that enough—he was brought by his master."

One of King's biggest, and most incredible, discoveries is that Khan had played another game against Capablanca—much earlier than their famous 1930 Hastings game. Their earlier game, in April 1929, was in a simul(!), only two days after he had arrived in London!

King: "You can imagine that when I found this game my jaw dropped, my jaw hit the floor."

The third world champion had played a tournament in Ramsgate but then stayed in London where he gave some simultaneous displays. In one of them, he faced Khan.

"The whole story of when he arrived in London is incredible, tells King. "He arrived on Friday, 26 April, 1929. On Saturday, he was introduced into London society by this very eminent politician Sir John Simon at the National Liberal Club, one of these very exclusive London clubs. He played a few games against a chap called Bruno Siegheim who was a former South African champion and did well against him. And then on Sunday, he played in a simul against Capablanca. So he basically stepped off the boat and started playing these games and beat Capablanca."

As King wrote in New in Chess Magazine, this was not just a win because Capablanca blundered his queen:

"Capablanca cracked in the face of stout defense. Expecting a swift victory, the Cuban was provoked into a full-scale assault, but the game had moved away from the smooth strategic paths where Capa was in his element towards a treacherous quagmire. At this moment, when he found himself in peril, Sultan Khan defended with coolness and originality—qualities he was to display so often in his later chess career."

King to Chess.com: "No one really understood how strong he was. Maybe Sultan Khan had no idea. Sir Umar had no idea. But with hindsight, it's sort of incredible. Why would he be playing against Capa in a simul?"

As King went through Sultan Khan's games, he got a better idea of what kind of player he was:

"I wanted to try and give a more balanced view and assess his style as well and just find out how strong exactly he was. Because that was the thing: In contemporary newspapers at the time, they didn't understand him at all. He had such a different style."

"First of all, his openings were terrible. That's because he didn't grow up playing western chess, although he did have some tuition and he learned some openings. He played systems; he didn't really play variations. And sometimes he just made horrible blunders in the opening.

"But also it seems to me that the areas where he was weakest in western chess were the areas that were different from the Indian rules. So, in the opening, he wasn't used to moving pawns two steps, and that meant that sometimes he pushed pawns ridiculously quickly in the opening.

"There's a game against Edgar Colle, who very cleverly played the Alekhine's Defense against him, and Sultan Khan just kept pushing these pawns. Basically he just self-destructed."

"In general, king safety was a terrible problem for him. In Indian chess, they didn't castle in the same way. They had this rule that the king could move like a knight once in the game. Very bizarre. Basically, that meant the king usually stayed in the middle of the board.

"And if you look at his games, so often he's careless with his king, and he leaves his king in the middle of the board, often just by choice. And sometimes it's brilliant, like when he beat Capablanca in Hastings. He didn't a castle, and it's perfect. But there are other games where his king just gets ripped off the board, and it's just kind of tragic."

Daniel King's "Sultan Khan: The Indian Servant Who Became Chess Champion of the British Empire" (with a foreword by former World Champion Viswanathan Anand) comprises 384 pages and can be found on the publisher's website.

Update: Sultan Khan's granddaughter Dr Atiyab Sultan has written a blog in which she claims that the book, and also some of King's quotes in this interview, are inaccurate at several points. You can find the blog here.