The Best World Chess Championship Matches In History

When we were preparing for the 2018 FIDE World Championship, Chess.com compiled a list of the most exciting world championship matches ever. But what were the best ones?

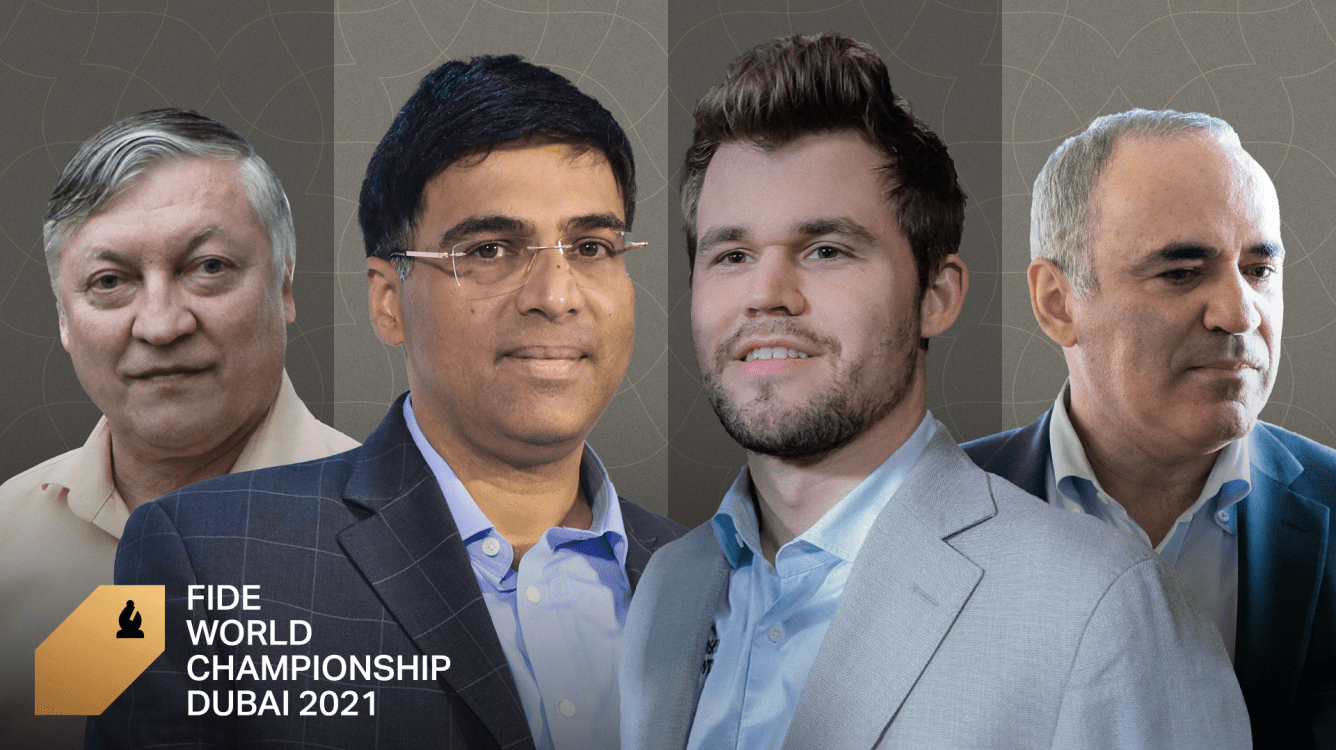

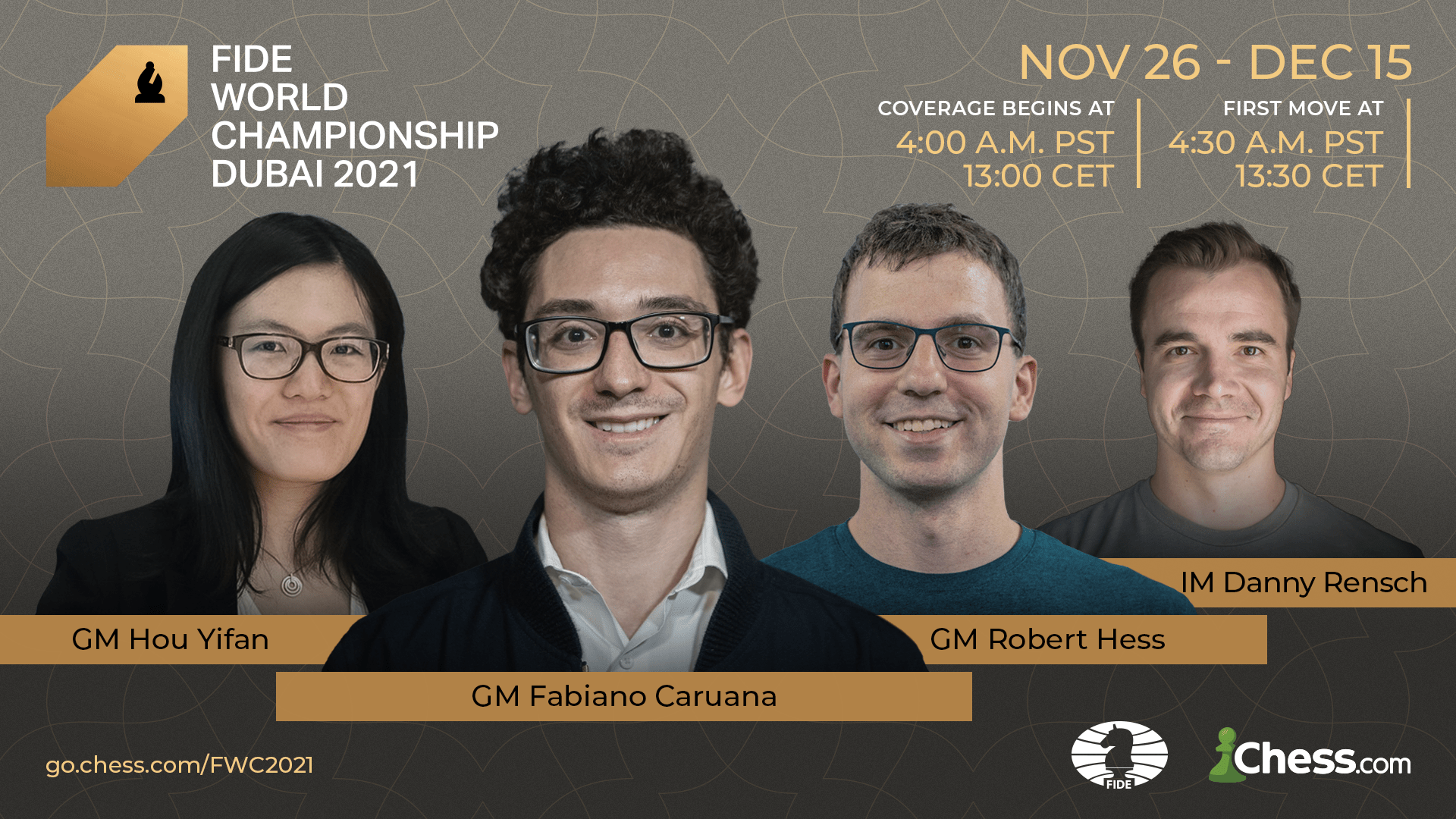

Now that the 2021 FIDE World Chess Championship between GM Magnus Carlsen and GM Ian Nepomniachtchi is underway, let's examine that subject of the best matches. It's hard to select these matches without ranking them, hence the chronological order.

Watch the 2021 FIDE World Chess Championship live

You can watch the 2021 FIDE World Chess Championship live on Chess.com/TV and on our Twitch and YouTube channels. You can also keep up with all the details here on our live events platform.

- Honorable Mentions

- Steinitz-Zukertort 1886

- Alekhine-Capablanca 1927

- Euwe-Alekhine 1935

- Botvinnik-Bronstein 1951

- Tal-Botvinnik 1960

- Fischer-Spassky 1972

- Karpov-Korchnoi 1978

- Kasparov-Karpov 1984-90

- Kramnik-Topalov 2006

- Anand-Topalov 2010

- Carlsen-Anand 2013

- Conclusion

Honorable Mentions

You get an honorable mention! You get an honorable mention! Everybody gets an honorable mention! (Oh, Oprah.)

I mean, it's the world championship, the premier event in chess. Every match is a great one in that regard. Even the worst match ever (either Emanuel Lasker vs. David Janowsky in 1910 or Alexander Alekhine vs. Efim Bogoljubov in 1934, if you're wondering) begins with the anticipation that a new best player in the world may be crowned.

A couple of matches require specific mention, though.

Lasker-Schlechter 1910

One of the weirdest ever matches, at least, was the second-shortest world championship match (1998 is the shortest). To this day nobody really knows with certainty what the conditions were. Both decisive games were odd as well, with Lasker blundering in the endgame of the fifth contest, and his esteemed opponent Carl Schlechter playing for a win in a drawn position in the 10th and final game despite leading the match.

So, as close as it was, it is not one of the best matches ever. What are they, then?

Steinitz-Zukertort 1886

How long can a record last that is set the first time a competitive event is held? As it turns out, while the first world championship match ended up a 10-5 advantage for Wilhelm Steinitz, he set a record that has been equaled but not (technically) yet been broken.

It was, in fact, Johannes Zukertort who led 4-1 after five games. After that, however, Steinitz mounted a furious comeback, taking a 6-4 lead before Zukertort won for the next, and last, time in the 10-5 match.

While a three-point lead was also overcome in 1935, no one has yet to win a world championship match when down four games or more (counting 1984/85 and 1985 as two matches, hence "technically" in the above). And now that title matches have invariably been fewer than 20 games for more than 25 years, the three-game comeback record might stand forever.

Because it was groundbreaking as the very first world championship and because it featured a record comeback, this game makes the list.

Alekhine-Capablanca 1927

Jose Capablanca's first title defense was expected to be rather easy for him. Although he lost the first game, by the end of the seventh he led 2-1 in a first-to-six-wins format. Things seemed to be back on track.

Then Capablanca didn't win again in the next 21 games. He dropped three of them to fall behind 4-2. Victory in game 29 brought Capa back within a point but, like Zukertort, such a win would be his last of the match.

The last game was much like the match: long, somewhat unclear until the very end, decided only after several moves (games). This match is still the second-longest in history by games played (34) and may always be because the world championship is now short with little incentive to dramatically expand it.

It was the first world championship where the result truly shocked the world. The games were interesting (if similar, given the infamous excessive use of the Queen's Gambit), and the match score was close (within two points) until the very last game.

Euwe-Alekhine 1935

A close match, a comeback, and an upset rolled into one 30-game battle to 15.5 points. It's rare in world championship history for such a setup or similar not to be either a rout (Alekhine's two matches with Bogoljubov) or an interminable battle of draws (1984/85), but this match featured 17 decisive games, 13 draws, and a mere one-point margin.

The match was tied three times: 1.0-1.0, 7.0-7.0, and 12.0-12.0. In the early going, Alekhine led by as many as three games, 5.0-2.0 and 6.0-3.0, before Max Euwe tied it. Alekhine then went up 10.5-8.5 before Euwe scored 5.5-1.5 on him from games 20-26. Game 26, where Euwe gave up a piece in exchange for three connected centralized passed pawns, was the best of the match.

Alekhine won game 27 (with controversy!) before three draws ended the match 15.5-14.5 in Euwe's favor. Alekhine had now experienced the other end of what he'd done to Capablanca until Euwe immediately gave Alekhine a return match which the Russian-born Frenchman won easily.

Botvinnik-Bronstein 1951

The first world title bout organized by FIDE was as close as a match can be: tied, only the second time in history that had happened, following the bizarre 1910 Lasker-Schlechter match. Israel Horowitz in 1973 deemed it "perhaps the most interesting" world championship to that point, which is saying something given another famous match had just concluded the year before. GM Mikhail Botvinnik vs. GM David Bronstein was also NM Dane Mattson's pick for the most exciting match ever.

Interesting and exciting must make for a pretty good match. Indeed, this one never saw more than a one-point margin, while the lead changed hands several times: Bronstein struck first in game five, was behind by game seven, tied it in game 11 only to immediately lose game 12, tied the match again in game 17 before falling behind in game 19.

But, after winning both the 21st and 22nd games, Bronstein led 11.5-10.5 and was on the brink of the title. Unfortunately, he lost game 23 and drew game 24. IM Hans Kmoch, describing Bronstein's style in his November 1951 recap of the 23rd game, wrote: "He cannot play for a draw, it seems. A draw comes to him only as the incidental result of partial failure."

Bronstein had many interesting comments to make about this match after the fact, but whatever happened behind the scenes, it made for a dramatic showdown. On the board, a future Botvinnik competitor would have even more of a flair for the dramatic, and with it came more success than Bronstein achieved.

Tal-Botvinnik 1960

No championship has featured a greater clash of styles than this one. GM Mikhail Tal won 75 percent of the decisive games, the second-highest percentage on the list, and also had the second-largest margin of victory, four points. Botvinnik fell behind 5.0-2.0 before scoring two straight wins, making the first nine games close despite the fact that Tal's most celebrated victories came in this portion: game one and game six. But Botvinnik never claimed another game while Tal doubled his win total with relatively solid chess, for him at least: game 17 was fairly wild, but game 19 was a positional game.

With the rout, the June 1960 issue of Chess Review that covered the match had nothing but superlatives to describe Tal. His "brand of chess... is rare Indeed in this era," drawing a comparison to Paul Morphy. He shows an "uncanny ability to conjure up combinations out of nothing," like Alekhine. And he upset Botvinnik psychologically as Lasker might have. Morphy, Alekhine, Lasker: quite the combination of players to be compared to.

Tal was certainly unique, and the fact that a player like him could win the title with ease surprised everyone. Although he inspired one future champion, in particular, no one has done it quite Tal's way since.

Fischer-Spassky 1972

It's tempting to be contrarian and leave this match out, but that's probably too contrarian.

Sure, the match wasn't close and the quality of play was uneven. (But the world championship often brings out a lot of uneven play.) GM Boris Spassky led 2-0 after two games, including a forfeiture. Then in games three through 10, GM Bobby Fischer crushed Spassky with five wins sans a loss. Three more games, with each player taking a win, loss, and draw, were followed by six more draws. Fischer then won the 21st game to take the title.

If it hadn't been for the 25 years of Soviet chess dominance and the Cold War overtones, such a match would not have kept anyone's attention. According to the final score, it was the most lopsided world championship match since 1961. Of course, all those sources of drama were present.

Game 13 was a microcosm of the match: The play itself was not spectacular, but the twists, turns, and drama certainly were.

In the November 1972 issue of Chess Life & Review, GM Anthony Saidy described the match this way: "From an artistic viewpoint, it was a spotty match that had its moments. It was far more interesting psychologically than artistically. There was just too much happening away from the board."

It almost was too much, wasn't it? Much has been made of Fischer singlehandedly toppling the Soviet chess machine. In pure chess terms, this statement rings correct (Saidy thought it was), but to convince Fischer to actually play, it took (per Saidy and GM Robert Byrne):

- his confidant, GM William Lombardy

- his lawyer, Paul Marshall

- his "chess mother," Lina Grumette

- a rich Briton named James Slater (who doubled the prize fund)

- the sportsmanship of his own opponent Spassky, who did not have to and yet agreed to play game three in a back room without cameras

- and even U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in an infamous phone call.

Karpov-Korchnoi 1978

Thanks to Fischer giving up his title in 1975 to GM Anatoly Karpov without a match, this was the first world championship to be played in six years. It was the longest wait for a world championship since 11 years had passed between the 1937 Alekhine-Euwe match and the 1948 world championship tournament, and even longer if you want to count specifically between matches: 14 years from 1937 until the 1951 Botvinnik-Bronstein bout.

Additionally, in 1976 GM Viktor Korchnoi had defected from the Soviet Union, and so yet again the match pitted the Soviet establishment against its fiercest rival. The intrigue of this match was in fact covered in a 2018 documentary, featuring several top grandmasters, called Closing Gambit (trailer below).

Unlike in 1972, in 1978 the Soviet establishment won. In a race to six wins, Karpov took a 4-1 lead after 17 games and 5-2 after 27 games. Yet (in a case of foreshadowing... stay tuned) he had trouble putting the match away. In fact, Korchnoi came roaring back with wins in games 28, 30, and 31 to tie the match.

The tie did not last.

Korchnoi almost tied that three-game comeback record. Instead, he had to qualify again three years later, for a match that was not nearly as close: 6-2 in just 18 games.

Kasparov-Karpov 1984-90

Is it cheating to count five matches as one? Arguably so: This article is about the best matches, not the best matchups. But arguably not: To only pick one would be an injustice to the others, and to pick many would crowd out other great matches.

Ultimately, counting their entire world championship experience together, GM Garry Kasparov "won" the title by a score of 21 wins to 19 in a "match" that took six years, five sets, six cities (Moscow, London, St. Petersburg, Seville, Lyon, and New York), and 120 games to complete. That would imply they were effectively some sort of co-champions during the stretch, but the real point is that no other championship rivalry before, since, or indeed likely ever will compare.

In the end, you can't say Kasparov didn't earn it. The last four sets all needed the full 24 games to decide the winner (although only money, not the title, was on the line in game 24 in a couple of cases), while the first one was canceled entirely as if it had never happened.

If you count the 1984-85 saga as one long match, then it was the only time a challenger won the title by drawing. In 72 games over 14 months from September 10, 1984 to November 9, 1985, both Karpov and Kasparov won eight games. But five of Kasparov's compared to three of Karpov's came in the 24-game set from 1985 that decided the title.

For drama off the board, little compares to the first two Kasparov-Karpov matches. For drama on the board, 1987 is the king, with Kasparov needing to win the 24th game to defend the championship, which he did. Whichever match you look at between these two players, it will be hard to come away unimpressed.

Kramnik-Topalov 2006

This match reunified the title after 13 years of competing claimants and, even independent of that controversy, was dramatic both on and off the board as well.

It looked like it would be over before it began when GM Vladimir Kramnik won the first two games. The next two games were draws, and then things got weird: GM Veselin Topalov's camp accused Kramnik of cheating from the bathroom. The conditions were then changed mid-match, and Kramnik forfeited the fifth game before the situation was resolved. With the match suddenly close, Topalov eventually took the lead with wins in games eight and nine before Kramnik came right back to win the 10th game.

From there the match went to the first rapid tiebreaks in world championship history. Kramnik drew as Black in the first game, which turned out to be key because White won the remaining three games. A Kramnik victory in the fourth and final rapid game decided the match in his favor.

2014 Chess.com coverage of an Olympiad game between the two players. Don't miss the brief appearances by other notable players.

Had Topalov won this match with Kramnik's game-five forfeit still on the books, the reunification would have dragged on through legal proceedings from Kramnik and may have even failed completely if Topalov's win stood and Kramnik did not accept it. Thus Kramnik's save in game 10 and the rapids arguably saved the respectability of the world championship itself from several more years of confusion.

Anand-Topalov 2010

Chess Life (in July 2010) called it "the most stirring world championship contest in years" and "one of the greatest world title battles of the modern era." Of the nine (including the ongoing) world championship matches since the reunification, it is the only one to be decided by a single game without needing rapid tiebreaks.

Anyone who doesn't like the rapid tiebreak system would consider this match the closest one yet of the post-unification matches to be decided by "real" (slow) chess. Say what you might about Topalov, he always puts up a fight.

It started with a bang, three decisive games out of four resulting in a 2.5-1.5 lead for GM Viswanathan Anand, after he had won one of our 10 greatest-ever world championship games. The players settled down with three draws before Topalov tied the match in the eighth game, which wound up the only decisive game from five to 11. In the 12th and final game, Anand pulled through, as Black, for the 6.5-5.5 victory.

The match didn't get to rapid in part because Topalov wanted to avoid rapid, seeing an advantage for Anand there, and so Topalov pushed instead of repeating on move 26. But perhaps treating a game that was not must-win as if it were must-win was not the wisest strategy. Topalov, who per Chess Life admitted as much after the match, never again played for the title.

Carlsen-Anand 2013

This is the only match on our list where one player failed to win a single game. Of course, there is more to a match than how close it is. Anand's last successful defense, the year before against GM Boris Gelfand, was one of the highly uninspired championship matches we've seen, despite being decided by a single rapid game.

The match in 2013 was one of the most highly-anticipated championship matches ever, as Carlsen had finally reached this stage despite having the world number-one FIDE rating for the better part of three years. He dropped out of the May 2011 Candidates (won by Gelfand) in protest of that tournament's format. The next Candidates was a round-robin instead of short knockouts, however, and Carlsen played in it and won to earn his spot in the 2013 Championship.

After Carlsen had won with three victories to zero in 10 games, GM Ian Rogers wrote in the February 2014 Chess Life that a "lesser endgame player than Carlsen would certainly not have won games five and six." At the start of game nine, the score was 5.0-3.0 with Anand needing to win two out of four just to get to tiebreaks. Instead, as Rogers wrote, Anand blundered in game nine and gave Carlsen "the match on a platter," with a drawn 10th game ending the match.

From this, we can say that while the match wasn't close on the scoresheet, it required a generational talent like Carlsen to make it so. Against someone else, the 43-year-old Anand may well still have been tied through eight games, but not against Magnus.

Conclusion

What do you think is the best world championship match ever: something on this list or is a big one missing? What matches don't belong on the list? Where will Carlsen-Nepomniachtchi rank when all is said and done?

Let us know your answers to these questions and more in the comments!