The Caro-Kann: Modern Times

In part 1 of this series on the Caro-Kann, I discussed the earliest beginnings of the opening, the origin of the name, and its first adoption by top players. It is always fascinating to learn about the beginnings of these openings, which today seem well-worn and familiar.

Today let's learn about how the Caro-Kann developed over the years, and next week we will learn about the various ways grandmasters have evolved to oppose it.

Last week, we saw that some of the first "top-level" grandmasters who used the Caro-Kann included Jose Raul Capablanca and Aron Nimzowitsch. In fact, throughout most of its history in the 20th century, the Caro-Kann has been an opening used by many players, although infrequently. There were few masters who specialized in it.

In the early years you can find many games by the Ukrainian master Stefan Izbinsky. The name of Savielly Tartakower also features prominently.

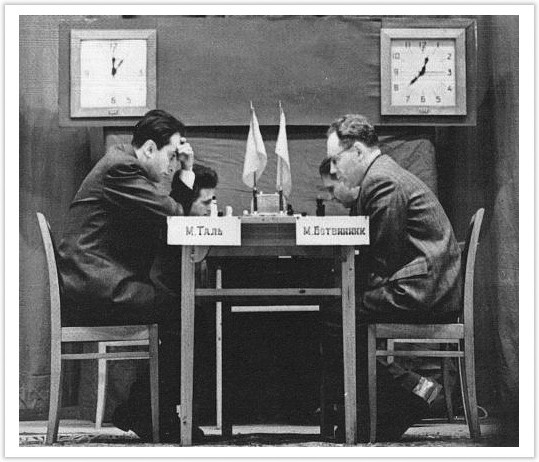

The first high-level uses of the Caro-Kann I will discuss were the two matches between Mikhail Tal and Mikhail Botvinnik in 1960 and 1961. Botvinnik, who always did everything deliberately, made a smart choice in using the Caro-Kann against his aggressive and tactical opponent.

In fact, throughout its history, the Caro-Kann has been used for just such a purpose -- to hold off and at the same time subtly provoke aggressive attackers.

In their first match, Tal generally used the open variations - 1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3. While he had a reasonable result competitively, the positions he was getting from the opening were not anything to write home about, and those games he won were mostly due to "luck."

For example, witness this famous game featuring the "ugly" 12.f4:

Tal won the world championship in this match. In 1961 a return match was held, and Botvinnik again turned to the Caro-Kann. Tal, probably not satisfied with the positions he was getting in the main line, decided to use the Advance Variation -- 3.e5.

Tal's preparation was based on meeting the most common response, 3...Bf5 with the strange-looking move 4.h4. With this move, White hopes to gain space on the kingside and "squeeze" the otherwise well-developed Bf5. In fact, 4.h4 remains a topical -- if rather difficult -- variation today.

I was interested to find that the move originated from the great Estonian player Paul Keres, who used it in some of his earliest games:

Thus in the 1961 Tal-Botvinnik match, the games with Tal as White revolved around the lines 3.e5 Bf5 4.h4 and the alternative 3.e5 c5, which Botvinnik also used. It turns out that the type of closed positions that resulted from these openings did not suit Tal's style, and despite his good preparation he scored minus one from the games with 3.e5.

Another great player who frequently used the Caro-Kann was Tigran Petrosian, and the opening was seen multiple times in his 1966 match with Boris Spassky. It does seem, however, that Petrosian lost confidence in the main lines where Black plays ...0-0-0 after the thirteenth game, where Spassky managed to crack the defense.

After this, Spassky switched to other defenses against 1.e4 in the remainder of the 1966 match and in the 1969 match. In fact, for a long time White was considered to have a small but stable advantage in the 4...Bf5 variation. It was only much later that castling kingside by Black became accepted as sound, which led to a great renewal of the Caro-Kann -- we will talk about this later.

The next great exponent of the Caro-Kann was the 12th world champion, Anatoly Karpov. Throughout his career, 1.e4 c6 was one of his main weapons, and it seemed to fit his pragmatic and sound style very well.

Early on, he met the main variation 1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.Nd2 dxe4 4.Nxe4 with 4...Bf5; but later he switched to his trademark 4...Nd7, preparing 4...Ngf6 (or, in many cases, 4...Ndf6).

Karpov, however seemed to shy away from using the Caro-Kann in his matches with Garry Kasparov, generally meeting 1.e4 (when Kasparov did play it; in their marathon matches he usually used 1.d4) with 1...e5.

It might seem surprising, but Kasparov himself consistently played the Caro-Kann early on in his career. However, he soon realized that his style was completely at odds with it, and switched to the Sicilian. A big part of advancing in chess involves finding the openings that go along with one's personality and style; even great players have to deal with this.

Today, the Caro-Kann has great popularity among the top players in the world as well as the second echelon of grandmasters. While it is still known as a relatively solid opening, certain developments in the main line have made it more applicable to sharp players who are looking for a win. Thus, for example, you can find many games by GM Shakhriyar Mamedyarov.

Today, the world's best players have a wider opening repertoire than in the past -- in part to avoid specific computer preparation, and in part because information stored on computers allows the relatively quick preparation of an opening before a game. Thus computers give both an incentive to have a wider repertoire as well as make it easier, and this affects the world's best players the most.

So, many include the Caro-Kann in their practice without it being their exclusive opening.

Developments in the main line:

Before we end the article, let us discuss for a moment a major change in recent years which made the Caro-Kann more popular.

This position commonly results from the main line of the Caro-Kann with 4...Bf5. Now Black can continue to develop with 10...e6 or 10...Ngf6 (it makes little difference), which White meets with either 11.Bd2 or 11.Bf4 (it makes some difference). In the past, Black would usually meet 11.Bf4 with 11...Qa5+ 12.Bd2 Qc7, and 11.Bd2 with the immediate 11...Qc7 -- both reaching the same position, soon followed by ...0-0-0.

It was seen as too dangerous for Black to castle kingside, due to the pawn on h6, which allows White to quickly open lines by g4-g5. However, games such as the above Spassky-Petrosian game gave these variations with ...0-0-0 a reputation as leading to slightly worse positions for Black. As a consequence, during the 1970s to 1990s, the move 4...Nd7 became pretty popular.

But later, some players, especially Bent Larsen, got the idea that ...0-0 was playable. Larsen showed that pressure on the d-file, along with pawn pushes such as ...a5 or ...b5 and queen sallies such as ...Qd5-f5 or ...Qd5-e4, gave Black enough counterplay to divert White from simply breaking through on the kingside.

This method of play has recently become far more popular than the old plan of ...Qc7 and ...0-0-0. Thus Black could meet Bd2 and 0-0-0 with a combination of ...e6, ...Ngf6, ...Be7, and ...0-0; while Bf4 could be met by the same way, when it is not clear that White benefits by the more active location of the bishop; or, after 10...e6 11.Bf4 Black could play 11...Qa5+ 12.Bd2 Bb4 13.c3 Be7 14.c4 Qc7 followed by 15...Ngf6 and ...0-0, when the c2-c4 push somewhat weakens White's queenside castled position.

These positions, with opposite side castling, have proven to be both reasonably reliable for Black as well as sharp and dynamic. Thus, the Caro-Kann began to appeal more to aggressive players who are looking to play for the full point with Black, as well.

Next week, we will have the last of my three-part series on the history of this opening, during which I will discuss the developments in White's various ways of opposing the Caro-Kann.

RELATED STUDY MATERIAL

- Read GM Smith's last article: The Caro-Kann: A History.

- Watch GM Ben Finegold's video: Beating Your Nemesis: Crushing the Caro!

- Take a Caro-Kann lesson in the Chess Mentor.

- Solve some puzzles in the Tactics Trainer.

- Looking for articles with deeper analysis? Try our magazine: The Master's Bulletin.