The Greatest Chess Tournaments Of All Time: An Engine's Perspective

Just as with everything else—hopefully—we learn more and more about chess as the years go by. Opening theory gets consistently deeper, tablebases have solved endgames with up to seven pieces on the board, and computers teach us more than we could ever have known about the game decades or centuries ago. Chess as it is played on the board by top players is only improving throughout time.

That truth was borne out by a recent Chess.com study of 12 historical tournaments based on computer-assessed accuracy. The "Computer Aggregated Precision Score" (CAPS) system that you see around Chess.com can also be converted into an approximate rating we'll call "Estimated Elo."

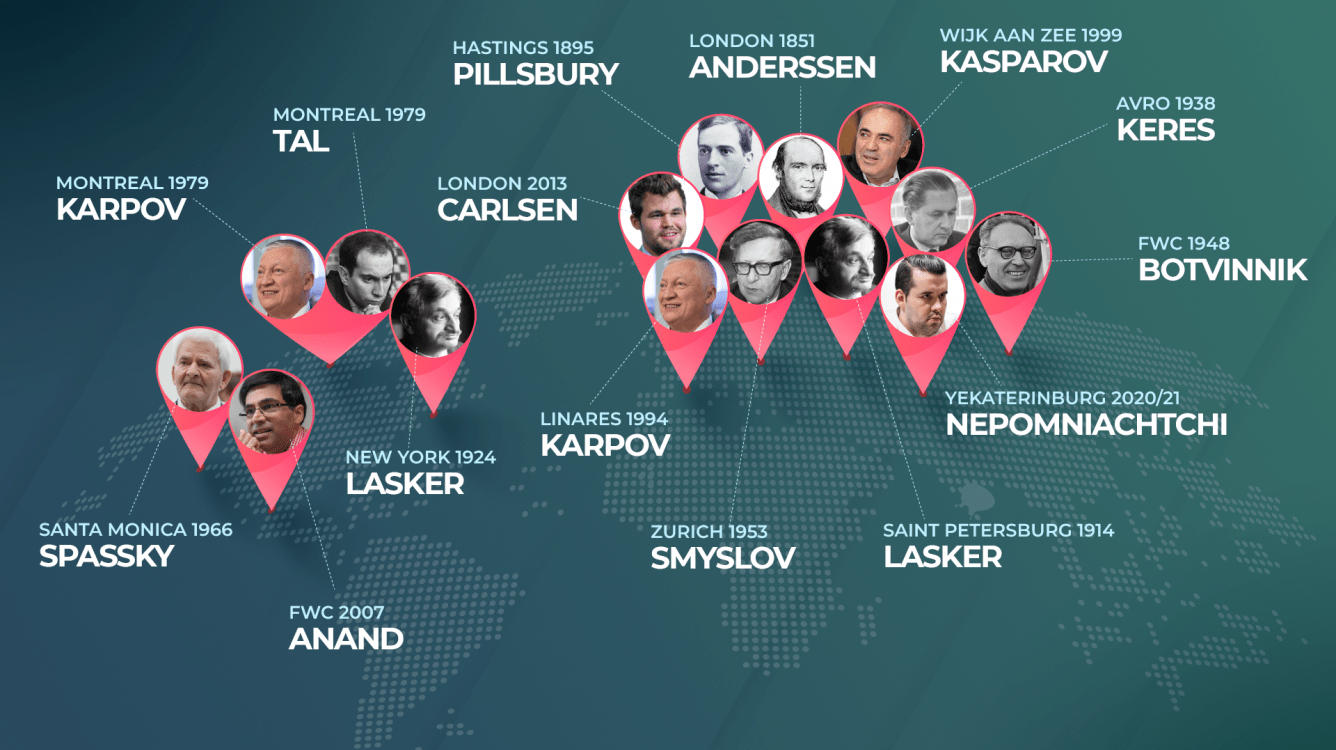

In this article, we will take a tour through 14 of the greatest tournaments of all time, revisiting the drama of these incredible events and looking afresh at how the strength of chess play has developed over time.

- What Are CAPS And Estimated Elo?

- London 1851

- Hastings 1895

- St. Petersburg 1914

- New York 1924

- AVRO 1938

- FIDE World Championship 1948

- Zurich Candidates 1953

- Santa Monica 1966

- Montreal 1979

- Linares 1994

- Wijk Aan Zee 1999

- FIDE World Championship 2007

- London Candidates 2013

- Yekaterinburg Candidates 2021

- Epilogue

What Are CAPS And Estimated Elo?

"Computer Aggregated Precision Score" (CAPS) is a system created by Chess.com. It shows how close a player's moves come to those recommended by the best computers and is expressed as a score on a 0-100 scale.

Every CAPS score can also be converted into an estimate of the rating a player would acquire over time, if playing regularly at that accuracy. For instance, a 96.7% accuracy should, over a sufficiently large sample of games, equate to a rating of approximately 2500.

London 1851

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Adolf Anderssen | 15.0 | 21 | 2120 | 91.6198 | 3 |

| 2 | Marmaduke Wyvill | 13.0 | 24 | 1885 | 86.8541 | 10 |

| 3 | Elijah Williams | 13.5 | 22 | 2015 | 89.5877 | 6 |

| 4 | Howard Staunton | 11.0 | 22 | 1914 | 87.4905 | 8 |

| 5 | Jozsef Szen | 12.5 | 17 | 2139 | 91.9660 | 2 |

| 6 | Hugh Alexander Kennedy | 10.0 | 19 | 1895 | 87.0747 | 9 |

| 7 | Bernhard Horwitz | 5.0 | 15 | 2008 | 89.4342 | 7 |

| 8 | James Swain Mucklow | 2.0 | 10 | 1492 | 78.1311 | 13 |

| Lost Rd. 1 | Henry Edward Bird | 1.5 | 4 | 2165 | 92.4265 | 1 |

| Lost Rd. 1 | Samuel Newham | 0.0 | 2 | 2118 | 91.5868 | 4 |

| Lost Rd. 1 | Johann Jacob Loewenthal | 1.0 | 3 | 2114 | 91.5123 | 5 |

| Lost Rd. 1 | Karl Mayet | 0.0 | 2 | 1878 | 86.7022 | 11 |

| Lost Rd. 1 | Lionel Adalbert Bagration Felix Kieseritzky | 0.5 | 3 | 1626 | 81.1476 | 12 |

| Lost Rd. 1 | Edward Shirley Kennedy | 0.0 | 2 | 1046 | 68.5305 | 14 |

| Lost Rd. 1 | Edward Lowe | 0.0 | 2 | <1000 | 64.8262 | 15 |

| Lost Rd. 1 | Alfred Brodie | 0.0 | 2 | <1000 | 53.1560 | 16 |

This storied event, the first great international tournament, could fit cozily into the under-2200 section of a modern event. Adolf Anderssen won the knockout event (the only such on our list, hence the uneven number of games played by each participant) with an impressive-enough Estimated Elo of 2120.

I find Anderssen to be somewhat underrated in the usual narrative of chess history. He wasn't part of Wilhelm Steinitz's "scientific" revolution, and he's usually seen as being part of the theoretical dead-end of Romanticism (this was Richard Reti's view.) But later developments, such as GM Mikhail Tal's wild style of play and the modern chess engine, show chess to be a wilder, more tactical game than the classicists suspected, and instead more in line with Anderssen's gift for combinations.

The contrast between Anderssen and his contemporaries is clear in his final-round mini-match with Marmaduke Wyvill. I had to look up Wyvill, who has I think the best name in all of chess history. It turns out he was a Member of Parliament, part of an aristocratic family that dates to William the Conqueror. He made it all the way to the finals at London 1851, but it's obvious that he wasn't in the same class as Anderssen (as his 1885 Estimated Elo demonstrates). Anderssen's play is crisp and logical and it feels like he barely has to try.

Hastings 1895

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Harry Nelson Pillsbury | 16.5 | 21 | 2516 | 96.8143 | 1 |

| 2 | Mikhail Chigorin | 16.0 | 21 | 2243 | 93.7170 | 9 |

| 3 | Emanuel Lasker | 15.5 | 21 | 2429 | 96.0666 | 2 |

| 4 | Siegbert Tarrasch | 14.0 | 21 | 2228 | 93.4836 | 10 |

| 5 | Wilhelm Steinitz | 13.0 | 21 | 2267 | 94.0734 | 7 |

| 6 | Emmanuel Schiffers | 12.0 | 21 | 2181 | 92.7022 | 11 |

| 7 | Curt von Bardeleben | 11.5 | 21 | 2394 | 95.6990 | 3 |

| 7 | Richard Teichmann | 11.5 | 21 | 2328 | 94.9193 | 5 |

| 9 | Carl Schlechter | 11.0 | 21 | 2280 | 94.2615 | 6 |

| 10 | Joseph Henry Blackburne | 10.5 | 21 | 2007 | 89.4263 | 18 |

| 11 | Karl August Walbrodt | 10.0 | 21 | 2164 | 92.4050 | 12 |

| 12 | David Janowsky | 9.5 | 21 | 2333 | 94.9781 | 4 |

| 12 | James Mason | 9.5 | 21 | 2124 | 91.7020 | 15 |

| 12 | Amos Burn | 9.5 | 21 | 2049 | 90.2551 | 17 |

| 15 | Isidor Gunsberg | 9.0 | 21 | 2124 | 91.6853 | 16 |

| 15 | Henry Edward Bird | 9.0 | 21 | 1982 | 88.9154 | 19 |

| 17 | Adolf Albin | 8.5 | 21 | 2151 | 92.1882 | 13 |

| 17 | Georg Marco | 8.5 | 21 | 2132 | 91.8312 | 14 |

| 19 | William Henry Krause Pollock | 8.0 | 21 | 1939 | 88.0201 | 20 |

| 20 | Jacques Mieses | 7.5 | 21 | 2248 | 93.7949 | 8 |

| 20 | Samuel Tinsley | 7.5 | 21 | 1618 | 80.9539 | 22 |

| 22 | Beniamino Vergani | 3.0 | 21 | 1749 | 83.8898 | 21 |

International chess is clearly at another level by the end of the 19th century. In London 1851, less than half of the participants have estimated Elo ratings over 2000; by Hastings 1895, the vast majority of players (17 out of 22) are over that threshold. Harry Pillsbury's Estimated Elo of 2516 is a world away from Anderssen's 2120.

It's worth repeating the story of Pillsbury's appearance. Pillsbury was a consummate dark horse, an almost completely unknown American player. Just before the tournament, which featured virtually every elite player of the era, there was only one gnomic letter predicting that "young Pillsbury will not be far out at the finish." As we will see, finishing with the best CAPS doesn't always mean winning a tournament, but Pillsbury achieved both at Hastings.

After a first-round loss, Pillsbury dominated the tournament and did so with a fresh, vigorous style of chess. Since Pillsbury never again actually won a tournament outright, there's a tendency to believe that he peaked at Hastings, but he was the world's #2 or #3 for the next decade; had he secured a match with Emanuel Lasker, it's likely that he would have made it very close.

St Petersburg 1914

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Emanuel Lasker | 13.5 | 18 | 2498 | 96.6738 | 4 |

| 2 | Jose Raul Capablanca | 13.0 | 18 | 2726 | 97.9424 | 1 |

| 3 | Alexander Alekhine | 10.0 | 18 | 2500 | 96.6920 | 3 |

| 4 | Siegbert Tarrasch | 8.5 | 18 | 2349 | 95.1818 | 6 |

| 5 | Frank James Marshall | 8.0 | 18 | 2418 | 95.9580 | 5 |

| 6 | Ossip Bernstein | 5.0 | 10 | 2305 | 94.6179 | 8 |

| 7 | Akiba Rubinstein | 5.0 | 10 | 2523 | 96.8620 | 2 |

| 8 | Aron Nimzowitsch | 4.0 | 10 | 2331 | 94.9570 | 7 |

| 9 | Joseph Henry Blackburne | 3.5 | 10 | 2086 | 90.9754 | 10 |

| 10 | David Janowsky | 3.5 | 10 | 2298 | 94.5176 | 9 |

| 11 | Isidor Gunsberg | 1.0 | 10 | 1814 | 85.3173 | 11 |

The players who most challenge the estimated Elo system are Lasker, GM David Bronstein, and GM Viktor Korchnoi—players who believe that chess is a struggle, whose games feature all sorts of mistakes and imbalances but who manage to get their opponents into a knife-fight where nerves and tactical sense prevail.

Nowhere is this more true than at St. Petersburg 1914. Capablanca's 2726 Elo estimate is of another class from Lasker's 2498, and yet it was Lasker who won the tournament. Lasker's style was mystifying to contemporaries. “It is not possible to learn from Lasker, only stand and wonder,” said GM Max Euwe famously, while Reti surmised that Lasker deliberately made inferior moves to muddy the position.

Computers don't really help clarify the mystery. According to the programs, Lasker's chess was inferior to some of his rivals. But he was the one winning. The simplest explanation is that the difference between top positions in a major tournament comes down to a handful of games. Capablanca put on a master class in the tournament and led most of the way but with a high percentage of draws. Lasker struggled early, barely qualified for the final round, but then went on a remarkable winning streak, setting up a famous game with Capablanca.

And at that point, Capablanca went to pieces. Lasker's famously controversial move 12.f5!? is no big deal according to the computer, and not even really anti-positional as the purists would have it. Capablanca was discombobulated enough by it that he missed the main point of the move, which was to occupy e6 with a knight, and lost with very little struggle—the computer awards just 43.4% accuracy to Capablanca for this game compared to 93.4% to Lasker. Capablanca then played one of the worst games of his career in the next round against Tarrasch. That was the difference in the tournament: Lasker's fighting spirit compensating for what a computer program would refer to as sub-optimal play.

New York 1924

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Emanuel Lasker | 16.0 | 20 | 2348 | 95.1678 | 7 |

| 2 | Jose Raul Capablanca | 14.5 | 20 | 2583 | 97.2613 | 1 |

| 3 | Alexander Alekhine | 12.0 | 20 | 2501 | 96.6939 | 3 |

| 4 | Frank James Marshall | 11.0 | 20 | 2566 | 97.1572 | 2 |

| 5 | Richard Reti | 10.5 | 20 | 2370 | 95.4357 | 6 |

| 6 | Geza Maroczy | 10.0 | 20 | 2212 | 93.2254 | 10 |

| 7 | Efim Bogoljubov | 9.5 | 20 | 2496 | 96.6599 | 4 |

| 8 | Savielly Tartakower | 8.0 | 20 | 2493 | 96.6330 | 5 |

| 9 | Fred Dewhirst Yates | 7.0 | 20 | 2220 | 93.3504 | 9 |

| 10 | Edward Lasker | 6.5 | 20 | 2319 | 94.8070 | 8 |

| 11 | David Janowski | 5.0 | 20 | 1999 | 89.2676 | 11 |

The same pattern holds in New York 1924. Again, Capablanca's Estimated Elo was far higher than Lasker's, by 200 points. This time Capablanca succeeded in winning one of their individual games. But once again Lasker won the tournament, even if his Estimated Elo would have placed him seventh out of eleven. A testament to his fighting spirit and his ability to win the big games.

Frank Marshall may have had a reputation for wild attacks and less-than-adequate defensive abilities, but you wouldn't know it from these charts. The computer very much approves of Marshall's play at New York, and he was up there in St. Petersburg as well. Meanwhile, David Janowsky failed to reach 90% in New York and wasn't great in St. Petersburg either. Of course, both of them were crushed 8-0 in attempts at the world championship in 1907 and 1910, respectively, by—you guessed it—Lasker.

AVRO 1938

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Paul Keres | 8.5 | 14 | 2724 | 97.9352 | 2 |

| 1 | Reuben Fine | 8.5 | 14 | 2695 | 97.8213 | 3 |

| 3 | Mikhail Botvinnik | 7.5 | 14 | 2603 | 97.3744 | 5 |

| 4 | Samuel Reshevsky | 7.0 | 14 | 2746 | 98.0162 | 1 |

| 4 | Alexander Alekhine | 7.0 | 14 | 2528 | 96.8992 | 6 |

| 4 | Max Euwe | 7.0 | 14 | 2515 | 96.8020 | 7 |

| 7 | Jose Raul Capablanca | 6.0 | 14 | 2654 | 97.6390 | 4 |

| 8 | Salomon Flohr | 4.5 | 14 | 2401 | 95.7809 | 8 |

AVRO was supposed to be the challenge of a younger generation, preeminently GM Mikhail Botvinnik and GM Samuel Reshevsky, to the elite mainstays, notably Capablanca and Alexander Alekhine. Instead, Capablanca and Alekhine were non-factors in the tournament, although the computer likes how Capablanca played more than his final standing.

Instead, the tournament was won by two virtual unknowns, 22-year-old GM Paul Keres and 24-year-old GM Reuben Fine. AVRO turned out to be the last significant international event for a decade and was, effectively, a sad swan song for both Alekhine and Capablanca.

Fine never quite matched his performance here, while Keres' success turned out to be very uncomfortable for the Soviet chess establishment. The tournament was meant to be the coronation of Botvinnik as Alekhine's challenger. But the war interfered with that, and the Soviet authorities now had a "Keres problem"—an Estonian of dubious ideology who had fully shown himself to be world championship caliber.

FIDE World Championship 1948

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Mikhail Botvinnik | 14.0 | 20 | 2528 | 96.9024 | 2 |

| 2 | Vasily Smyslov | 11.0 | 20 | 2686 | 97.7850 | 1 |

| 3 | Samuel Reshevsky | 10.5 | 20 | 2500 | 96.6879 | 3 |

| 3 | Paul Keres | 10.5 | 20 | 2397 | 95.7355 | 4 |

| 5 | Max Euwe | 4.0 | 20 | 2277 | 94.2179 | 5 |

The 1948 World Championship tournament was a real mess from a playing quality standpoint, with all of the top players playing well below their peak. The five players here averaged an Estimated Elo of just 2478, 130 points below the 2608 averaged by the AVRO players a decade previously. Even 35 years earlier at St. Petersburg, the top five finishers averaged 2533, a 55-point edge, including a score from Capablanca that would have been the best one here. Pillsbury's accuracy more than 50 years prior at Hastings nearly matched Botvinnik's winning performance.

GM Vasily Smyslov, the only player at this tournament who was not at AVRO, played much more accurately than anyone including Botvinnik in the 1948 tournament, but Smyslov was in a more peaceable mood and the only player in the tournament to draw half his games. Keres' very low score (over 300 points lower than at AVRO 1938) offers some corroboration to the long-held suspicion that he was not trying to win.

Zurich Candidates 1953

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Vasily Smyslov | 18.0 | 28 | 2567 | 97.1641 | 6 |

| 2 | Paul Keres | 16.0 | 28 | 2587 | 97.2876 | 4 |

| 2 | David Bronstein | 16.0 | 28 | 2504 | 96.7233 | 10 |

| 2 | Samuel Reshevsky | 16.0 | 28 | 2488 | 96.5921 | 11 |

| 5 | Tigran Vartanovich Petrosian | 15.0 | 28 | 2435 | 96.1207 | 13 |

| 6 | Efim Geller | 14.5 | 28 | 2577 | 97.2276 | 5 |

| 6 | Miguel Najdorf | 14.5 | 28 | 2510 | 96.7671 | 9 |

| 8 | Mark Taimanov | 14.0 | 28 | 2565 | 97.1503 | 7 |

| 8 | Alexander Kotov | 14.0 | 28 | 2403 | 95.8018 | 14 |

| 10 | Yuri Averbakh | 13.5 | 28 | 2759 | 98.0604 | 1 |

| 10 | Isaac Boleslavsky | 13.5 | 28 | 2596 | 97.3366 | 3 |

| 12 | Laszlo Szabo | 13.0 | 28 | 2442 | 96.1860 | 12 |

| 13 | Svetozar Gligoric | 12.5 | 28 | 2539 | 96.9761 | 8 |

| 14 | Max Euwe | 11.5 | 28 | 2655 | 97.6465 | 2 |

| 15 | Gideon Stahlberg | 8.0 | 28 | 2363 | 95.3452 | 15 |

It's hard for me to explain why near-last-place Euwe has the second-highest estimated Elo of anybody at Zurich 1953, although it's true that he played better than his score would indicate and actually played the game of his career against GM Efim Geller. That's just one of several anomalies about estimated Elo scores at this event. GM Yuri Averbakh lost a famous brilliancy to GM Alexander Kotov but apparently deserved much better than a 10th place finish while Kotov was nearly at the bottom of the accuracy chart. Meanwhile, Reshevsky and Bronstein overperformed against their computer accuracy. Another surprise is the relatively low score of GM Tigran Petrosian, who finished a strong fifth.

Santa Monica 1966

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Boris Spassky | 11.5 | 18 | 2826 | 98.2681 | 1 |

| 2 | Robert James Fischer | 11.0 | 18 | 2662 | 97.6783 | 2 |

| 3 | Bent Larsen | 10.0 | 18 | 2633 | 97.5375 | 4 |

| 4 | Lajos Portisch | 9.5 | 18 | 2650 | 97.6230 | 3 |

| 4 | Wolfgang Unzicker | 9.5 | 18 | 2629 | 97.5150 | 5 |

| 6 | Samuel Reshevsky | 9.0 | 18 | 2548 | 97.0390 | 7 |

| 6 | Tigran Vartanovich Petrosian | 9.0 | 18 | 2495 | 96.6519 | 10 |

| 8 | Miguel Najdorf | 8.0 | 18 | 2582 | 97.2572 | 6 |

| 9 | Borislav Ivkov | 6.5 | 18 | 2536 | 96.9565 | 8 |

| 10 | Jan Hein Donner | 6.0 | 18 | 2519 | 96.8345 | 9 |

Petrosian, by now the reigning world champion, once again finished higher than his computer accuracy would indicate. I would have assumed his chess to be simpatico with the computer's vision, but while he was the overall most accurate player for a time in the late 1950s, he spent much of his world championship reign outside the top five.

Montreal 1979

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Mikhail Tal | 12.0 | 18 | 2812 | 98.2265 | 1 |

| 1 | Anatoly Karpov | 12.0 | 18 | 2585 | 97.2751 | 4 |

| 3 | Lajos Portisch | 10.5 | 18 | 2550 | 97.0523 | 6 |

| 4 | Ljubomir Ljubojevic | 9.0 | 18 | 2684 | 97.7763 | 2 |

| 5 | Boris Spassky | 8.5 | 18 | 2563 | 97.1366 | 5 |

| 5 | Jan Timman | 8.5 | 18 | 2529 | 96.9036 | 7 |

| 7 | Robert Huebner | 8.0 | 18 | 2595 | 97.3292 | 3 |

| 7 | Lubomir Kavalek | 8.0 | 18 | 2521 | 96.8462 | 8 |

| 7 | Vlastimil Hort | 8.0 | 18 | 2443 | 96.1974 | 10 |

| 10 | Bent Larsen | 5.5 | 18 | 2455 | 96.3092 | 9 |

I didn't know anything about this tournament, a glossy "Tournament of the Stars" which was won jointly by Tal and GM Anatoly Karpov. This was at the peak of Tal's renaissance. He dominated at the Interzonal at Riga the same year and there seemed good chances that he would retake the world title after a 20-year hiatus. Unfortunately, he did not make it out of the quarterfinals of the ensuing Candidates.

Tal's chess at this time was very different from what it had been in his heyday from 1957 to 1961. "Perhaps I have become a little older and see a little more for my opponent and a little less for myself," Tal said after the tournament. "I am convinced that, protected by all this armor, I would simply tear to pieces that candidate of the 1960s."

It's surprising, given their personality differences, to realize how close he and Karpov were at this time. They essentially played this tournament as a ‘team,' preparing and analyzing together. In terms of computer accuracy, that turned out to be a better deal for Tal, but it worked out for both of their results.

Linares 1994

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Anatoly Karpov | 11.0 | 13 | 3000+ | 98.6833 | 1 |

| 2 | Garry Kasparov | 8.5 | 13 | 2774 | 98.1103 | 2 |

| 2 | Alexey Shirov | 8.5 | 13 | 2630 | 97.5228 | 6 |

| 4 | Evgeny Ilgizovich Bareev | 7.5 | 13 | 2774 | 98.1095 | 3 |

| 5 | Vladimir Kramnik | 7.0 | 13 | 2758 | 98.0580 | 4 |

| 5 | Joel Lautier | 7.0 | 13 | 2634 | 97.5414 | 5 |

| 7 | Viswanathan Anand | 6.5 | 13 | 2622 | 97.4820 | 7 |

| 7 | Gata Kamsky | 6.5 | 13 | 2607 | 97.3969 | 8 |

| 7 | Veselin Topalov | 6.5 | 13 | 2464 | 96.3889 | 11 |

| 10 | Vassily Ivanchuk | 6.0 | 13 | 2477 | 96.5009 | 10 |

| 11 | Boris Gelfand | 5.5 | 13 | 2526 | 96.8869 | 9 |

| 12 | Miguel Illescas Cordoba | 4.5 | 13 | 2439 | 96.1624 | 12 |

| 13 | Judit Polgar | 4.0 | 13 | 2277 | 94.2256 | 14 |

| 14 | Alexander Beliavsky | 2.0 | 13 | 2437 | 96.1387 | 13 |

In the tournaments surveyed so far, the top achievements have been Spassky's 2826 estimated Elo at Santa Monica and Tal's 2812 at Montreal. But at Linares 1994, Karpov's play was literally off-the-charts, topping 3000. Karpov was thought by some to be losing it by 1994. Two years earlier, he was knocked out of a world championship cycle before the finals for the first time in his career. Linares was an unexpected tour de force as well as his last truly great result: he was undefeated in 13 games with an amazing nine wins, including an atypically sacrificial brilliancy against GM Veselin Topalov.

Cordoba, the local "favorite son" Spaniard, did much better than the local Dutchman Reinderman in our next tournament.

Wijk Aan Zee 1999

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Garry Kasparov | 10.0 | 13 | 2676 | 97.7401 | 9 |

| 2 | Viswanathan Anand | 9.5 | 13 | 2845 | 98.3193 | 5 |

| 3 | Vladimir Kramnik | 8.0 | 13 | 3000+ | 98.7439 | 1 |

| 4 | Alexey Shirov | 7.0 | 13 | 2867 | 98.3729 | 3 |

| 4 | Ivan Sokolov | 7.0 | 13 | 2846 | 98.3209 | 4 |

| 4 | Jan Timman | 7.0 | 13 | 2799 | 98.1902 | 7 |

| 4 | Jeroen Piket | 7.0 | 13 | 2617 | 97.4515 | 11 |

| 8 | Peter Svidler | 6.5 | 13 | 2891 | 98.4304 | 2 |

| 8 | Vassily Ivanchuk | 6.5 | 13 | 2705 | 97.8635 | 8 |

| 10 | Veselin Topalov | 6.0 | 13 | 2629 | 97.5145 | 10 |

| 11 | Rustam Mashrukovich Kasimdzhanov | 5.0 | 13 | 2530 | 96.9159 | 13 |

| 12 | Loek van Wely | 4.5 | 13 | 2553 | 97.0740 | 12 |

| 13 | Alexey Vladislavovich Yermolinsky | 4.0 | 13 | 2808 | 98.2149 | 6 |

| 14 | Dimitri Reinderman | 3.0 | 13 | 2285 | 94.3348 | 14 |

The computer is being surprisingly unkind to GM Garry Kasparov, who, by every other measure, dominated at Wijk aan Zee 1999. Conversely, the computer gives GM Vladimir Kramnik an Estimated Elo of over 3000. Not so surprising given his precise and logical play, but, as Lasker demonstrated, what really counts is won games, not playing accuracy. Kasparov kept his opponents on their toes and he easily won the tournament (which included one of the most celebrated games of his career against Topalov) even though his Estimated Elo would put him ninth out of fourteen. The computer figures his one loss, to Sokolov, to be a pretty weak game (81% at depth 30), which didn't help.

Shoutout to Chess.com contributor GM Alex "Yermo" Yermolinsky for his computer accuracy in this tough field, outperforming Kasparov and finishing in the top half by the metrics.

Mexico City World Championship 2007

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Viswanathan Anand | 9.0 | 14 | 2890 | 98.4284 | 4 |

| 2 | Vladimir Kramnik | 8.0 | 14 | 2916 | 98.4874 | 2 |

| 3 | Boris Gelfand | 8.0 | 14 | 2914 | 98.4819 | 3 |

| 4 | Peter Leko | 7.0 | 14 | 2952 | 98.5596 | 1 |

| 5 | Peter Svidler | 6.5 | 14 | 2795 | 98.1780 | 5 |

| 6 | Alexander Morozevich | 6.0 | 14 | 2541 | 96.9916 | 8 |

| 7 | Levon Aronian | 6.0 | 14 | 2704 | 97.8572 | 6 |

| 8 | Alexander Grischuk | 5.5 | 14 | 2634 | 97.5394 | 7 |

GM Viswanathan Anand won the world championship despite middle-of-the-pack accuracy, but he was only a couple fractions of a percent away from the player with the best accuracy score. Few consider GM Peter Leko when we talk about the best players never to become world champion. Yet in addition to his accuracy at this championship tournament, he was the youngest grandmaster ever for a time and tied Kramnik in a title bout in 2004 (Kramnik, as the reigning champ, was declared the winner). It's a resume most players would kill for.

By now, we are of course at a completely different level from London 1851 or Hastings 1895. GM Alexander Morozevich, the player with the lowest Elo here, would have had the highest at Hastings. A score in the 2800s or 2900s, equivalent to 98% computer accuracy, no longer guarantees first place.

In defense of the old-timers, though, it's worth pointing out that they didn't know how computers play or what "computer-like accuracy" would look like. They were figuring it out themselves, making guesses about the right way to play. By the 2000s, players had the ability to check the back of the book.

London Candidates 2013

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Magnus Carlsen | 8.5 | 14 | 2971 | 98.5961 | 5 |

| 2 | Vladimir Kramnik | 8.5 | 14 | 3000+ | 98.7700 | 1 |

| 3 | Peter Svidler | 8.0 | 14 | 2999 | 98.6472 | 4 |

| 3 | Levon Aronian | 8.0 | 14 | 2735 | 97.9772 | 6 |

| 5 | Alexander Grischuk | 6.5 | 14 | 3000+ | 98.7191 | 2 |

| 5 | Boris Gelfand | 6.5 | 14 | 3000+ | 98.6650 | 3 |

| 7 | Vassily Ivanchuk | 6.0 | 14 | 2730 | 97.9575 | 7 |

| 8 | Teimour Radjabov | 4.0 | 14 | 2601 | 97.3660 | 8 |

If, by the 2000s, an Estimated Elo in the 2800s or 2900s was no guarantee of success, then, by the 2010s, a score in the 3000s was no big deal. Kramnik, GM Alexander Grischuk and GM Boris Gelfand both passed that milestone while having disappointing tournaments. Meanwhile, this was the first tournament on the list where everyone has at least 97% accuracy and a 2600 Estimated Elo.

It was an especially close tournament accuracy-wise. Five players had CAPS scores of 98.5 or higher, including the winner GM Magnus Carlsen, with no one above the 98.8 mark. This tournament could really have gone anyone's way by the computer's reckoning, and it appears at first glance that Carlsen may have backed into the world championship. Not only did he fail competitively, losing his last-round game to GM Peter Svidler, but he finished fifth place in estimated Elo. Fortunately for Carlsen, Kramnik failed in the clutch as well, losing in the last round to the ever-unpredictable GM Vassily Ivanchuk.

Yekaterinburg Candidates 2020-21

First Half

| Standing | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Maxime Vachier-Lagrave | 4.5 | 7 | 3000+ | 98.8158 | 1 |

| 2 | Ian Nepomniachtchi | 4.5 | 7 | 2926 | 98.5076 | 6 |

| 3 | Fabiano Caruana | 3.5 | 7 | 2971 | 98.5964 | 3 |

| 4 | Wang Hao | 3.5 | 7 | 3000+ | 98.8095 | 2 |

| 4 | Anish Giri | 3.5 | 7 | 2926 | 98.5074 | 7 |

| 6 | Alexander Grischuk | 3.5 | 7 | 2946 | 98.5478 | 4 |

| 7 | Ding Liren | 2.5 | 7 | 2745 | 98.0114 | 8 |

| 8 | Kirill Alekseenko | 2.5 | 7 | 2938 | 98.5329 | 5 |

Second Half

| Standing (2nd half only) | Player | Score | Games | Effective Elo | CAPS | Rank by CAPS |

| 1 | Ding Liren | 4.5 | 7 | 3000 | 99.0320 | 1 |

| 2 | Ian Nepomniachtchi | 4.0 | 7 | 3000 | 98.6806 | 2 |

| 2 | Fabiano Caruana | 4.0 | 7 | 2973 | 98.6011 | 3 |

| 2 | Anish Giri | 4.0 | 7 | 2640 | 97.5694 | 8 |

| 5 | Maxime Vachier-Lagrave | 3.5 | 7 | 2929 | 98.5151 | 5 |

| 5 | Alexander Grischuk | 3.5 | 7 | 2655 | 97.6460 | 7 |

| 7 | Kirill Alekseenko | 3.0 | 7 | 2936 | 98.5288 | 4 |

| 8 | Wang Hao | 1.5 | 7 | 2782 | 98.1352 | 6 |

In the opening half of Yekaterinburg, all players topped 98% accuracy, the first time that had happened in a tournament. From the narrow perspective of degrees of excellence, the 2021 restart was a step backward, with a couple of players dipping below the 98% threshold. On the other hand, GM Ding Liren became the first player, at least in the tournaments surveyed, to go through an entire tournament with 99% accuracy. Unfortunately, his medicore game results in the first half put him in the middle of the pack overall, despite the best win rate of the second half.

GM Wang Hao, who had awful results in the second half and announced his retirement afterward, actually didn't play that terribly according to the silicon, outperforming two of his second-half opponents. The Marmaduke Wyvills and Samuel Tinsleys of tournaments past couldn't even have imagined the quality of chess that we now enjoy in the 21st century.

Epilogue

These 12 tournaments aren't the only way to use the CAPS system to analyze past play.

The Chess.com staff recently performed a significant, if underappreciated, service to humanity by running the complete games archive of 78 top players in chess history through an engine to try and figure out who really was the best of all time.

To those lucky few who spend a lot of time thinking about chess history, this is catnip—a chance to actually settle these nagging, oddly irritating questions about how to compare players from different eras.

The next time you have five minutes and nineteen seconds to procrastinate with, you probably should spend them on this video, with its gorgeous graphics and soaring music, like a soundbath of geekiness.

As far as I can tell, this isn’t even work, really, just how the staff spends their free time.

Which effective Elo performance shocked you the most? Which tournament performance do you find to be the most impressive? Let us know in the comments below!