Think Twice Before A Threefold Repetition

Nowadays, it is normal for chess players of all levels to make a quick draw once in a while. The so-called "Sofia Rules" and other measures that attempt to prohibit draws by mutual agreement are typically applied in elite tournaments and even world championship cycles, but they are not yet relevant in most (open) tournaments and competitions.

Will the first player who's never succumbed to the temptation of finishing the game quickly with half a point please stand up?

There are several ways, of course, to circumvent even the strictest of rules. A perpetual check is a rare occasion early in a game, but we all know there are certain opening variations that feature an early threefold repetition that can't really be prevented as it would force the players to play weaker alternatives. Here's one that doesn't require any thinking at all, from the Sicilian Najdorf:

A little more sophisticated is the following, also from the Sicilian (Sveshnikov variation):

This has happened in countless games, including Grischuk-Leko, Beijing 2014 (blitz) and in an episode of the sister-act Anna Muzychuk-Mariya Muzychuk, World Rapid Championship 2014.

And then there is this one in the Zaitsev Variation of the Ruy Lopez, probably the most famous threefold-repetition variation of all:

The appealing thing about this line for White is that he can try this repetition for free before deciding whether to play for a win or not, but that Black has no good way to avoid it if he wants to play the Zaitsev. That sounds very convenient for White, doesn't it? Well, it comes at a price, because what do you do after the first repetition? Do you repeat again?

I faced that dilemma once against a stronger opponent, and in the end I decided to take the draw. I must confess that I still feel a little ashamed of it, although it was a team game, and we did win the match in part because of this draw. Still, I felt bad afterwards.

As natural as this may sound to us now, there once was a time when a clear threefold repetition did not automatically lead to a draw. (Let's ignore the technicalities of claiming a threefold repetition here, which are far from trivial and have led to several high-profile incidents throughout chess history.)

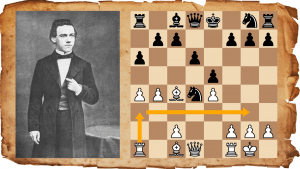

Wilhelm Steinitz via Wikipedia.

Here's a game by William Steinitz, who later became the first world champion, which nicely illustrates the problems players faced in the early days. It's a remarkable game for more than one reason, as we will see.

An amazing fight! Some years after this game (in 1883) the drawing rules for threefold repetitions were first written down (albeit rather vaguely).

It's quite fitting that the endgame of king and rook versus king and knight (or KRKN) is featured in Neumann-Steinitz, as it's arguably the oldest known theoretical draw in chess history. We know this because the endgame rook versus knight was already analyzed in Persia in the ninth (!) century AD.

The ancient masters, playing the game of shatranj, already realized that this endgame is not always a draw. (Remember that in shatranj, the king, rook and knight moved in the same way as in modern chess, whereas the queen and bishop moved differently.)

Now have a look at following game, which makes Neumann and Steinitz look like amateurs. And it wasn't played in the 19th century—it was played in 2010. This game shows that despite the clear progress made since the time of Steinitz, it's still not always desirable to claim a threefold repetition!

What happened here?! Why didn't the players agree to the draw after three repetitions? After all, we don't live in the 19th century.

Well, during this game Loek van Wely participated in an experiment in which he wore sensors recording his stress-levels during the game. When his young opponent started repeating moves, he became extremely annoyed. He hadn't expected him to go for a "cheap" repetition at all. So he chose to ignore White's draw offers until in the end, Bok had to claim the repetition.

Afterwards, Van Wely explained to the press that the game was a disgrace and that someone who receives a wildcard from the organizer should not go for quick draws with White. "He goes straight for the draw like an idiot," Van Wely said.

Bok learned a valuable lesson that day: Sometimes you may get a quick draw, but you may also lose your face. So be careful what you wish for!