USA vs Yugoslavia

The Introduction

The U.S.S.R team totally demolished the U.S.A. team in a Radio Chess Match played from Sept.1-4, 1945. Not only did this event shine a glaring spotlight on the Soviet chess advancement, but it sparked a minor popularity in radio matches.

Radio matches weren't new and had been around in one form or another for decades (see Bill Wall's amassed information of radio-chess here).

The Lethbridge [Canada] "Herald," printed the following on May 10, 1927:

Chess Match by Radio, Canberra to London

LONDON. A Twelve thousand mile wireless chess match arranged between members of the British house of commons, sitting In a committee room of the house and a team of Australian legislators at Canberra, the new Australian capital, began yesterday, but, made slow progress. The Duke of York, who [was] at the celebration of the Australian capital had the honor of the first move at Canberra, while Premier Baldwin had the first move in London. Transmission, which was by the wireless beam system, encountered numerous difficulties, and after a hour of play the match was called a draw as the duration of time made it necessary for the Australians to be in play at midnight and they did not want to stay up late.

This was a 6-board event.

It seems that this London-Sydney match might have been the first international radio match attempt.

The first successful international radio-match was played on Jan. 12, 1941 between the team of the Santiago de Cuba Chess Circle (shown below) defeated the Trujillo City Chess Club of the Dominican Republic. The photo with this information was published in "Chess Review" of Feb. 1946. The caption tells us "The score was 3.5-2.5. On the extreme left is Lt. Humberto Diez de la Noval."

From June, 19- 20 1946, the Soviets beat the team from Great Britain in a radio match. Great Britain, in turn, defeated Australia in a radio match played Oct. 4-7, 1947. Australia, though, had just beaten Canada in a radio match from June 13-14, 1947. Also, in 1946 Spain beat Argentina, although Argentina would get its revenge in a 1949 match and in 1948 Great Britain tied its radio match with Australia while the US beat Cuba.

In 1950, Yugoslavia wanted to ride that wagon and challenged the U.S.A. to a radio match The challenge was immediately accepted.

The Preliminaries

The U.S. team had difficulties even before the match began. In January 1950 the line-up was published:

Shortly before the match was to begin Isaac Kashdan took ill:

"Chess Review" March 1950

"Chess Review" March 1950

Arthur Bisguier, the U.S. Jr. champion and champion of the Manhattan Chess Club was selected to replace Kashdan. But then, the day before the match, Steiner dropped out. This led to a scramble to get a replacement. Olaf Ulvestad, the wonder from Washington state, was picked but he was slated to give a simul in Cleveland, Ohio. In a mad rush, Larry Evans flew from New York to Cleveland as Ulvestad's substitute while Ulvestad was flying to New York.

"Chess Life" March 5, 1950

"Chess Life" March 5, 1950

Even with a replacement provided for Steiner's spot, a series of incriminatory letters were printed in Chess Life.

For clarity's sake it should be understood that Chess Review, a private publication, was one of the main sponsors of this event. Chess Life, the official publication for the USCF, was only remotely involved officially in this radio match. Chess Review was owned by Israel Albert Horowitz while Chess Life, was edited by Montgomery Major. Horowitz published no letters concerning the controversy while Chess Life, while not publishing much at all about the match itself, seemed to enjoy publishing contentious letters.

Although it was Steiner who breached the contract, Horowitz was the main target of the defamatory letters. The issue was complicated by misinformation and lingering indignation on the old subject of New York's chess dominance.

Below are the most relevant letters:

This first one was written by Jame Bolton of New Haven, Connecticut. He was apparently spurred to write more on assumptions than facts.

Chess Life, March 5, 1950

Dear Sir:

I have just heard that the United Slates champion was not allowed to play first board not Yugoslavia, and finally dill not Play at all. This Is to record my complete support of our champion, and vehement opposition to everything represented by that confounded committee. Since when Is the champion not the champion? Does the Biennial Championship mean nothing when opposed by selfish prejudice? Did or did not Steiner win the right to be considered our strongest player in a fair and honest tournament established to determine that question? For some time past I have observed the encroachments of a certain regional chess clique, actuated by self-Interest, and aiming to destroy that democratic, competitive system of chess tournaments which was introduced by the U.S.C.F., and in its place revert to the obsolete invitational method, which so long stifled the rise of new players. This trend must stop, and I will support all efforts to stop it.

Indignantly,

JAMES BOLTON Champion of New Haven

Tony Santasiere put in his 2 cents in a very bizarre letter. It seems he had a personal axe to grind.

Chess Life, March 5, 1950

Dear Montgomery:

I dare you to publish this letter in CHESS LIFE.

How is an American team chosen? And what part does the United States Chess Federation play in its choice? I say that the team is chosen by a dictator called Al Horowitz, and that the USCF plays little or no part in its choice. I say that Al Horowitz chooses his friends or those he is interested in, makes it a point to ignore those he dislikes. I take you back to 1945. The team to play Russia was to be chosen. Horowitz made the choice, and refused to include me on the team, even though I was then U. S. Open Champion. Only a strenuous effort by USCF president (then) Elbert Wagner forced my choice. Every member of that team except Seidman (and myself) was a member of the Manhattan Chess Club. Every member of that team was a New Yorker (we, who know Steiner, still count him as such.) The night before play, I had an operation in the mouth. The day of play I was still sick. I explained all this to Harkness, and offered to withdraw. Be never even answered me! not a word. I played fifteen hours that day, twelve hours on succeeding days, all under a handicap of health. I lost both games to Bronstein (Reshevsky, Denker, Kashdan and Seidman also lost two games), but they were two splendid fights, and I alas proud of them. Subsequently, in the Chess Review, all the team members were asked to annotate their own games (and probably paid for It) except Santasiere. His games were written up in a most prejudiced and offensive fashion by the editor. Even so good a friend of the Review as Nat Helper was moved to remark to the editor—"Have you nothing good to say about Santasiere?" Came the year 1946. And some $25,000 donated by Mr. Wertheim to send a team to Russia. Horowitz made the choice. Santasiere was not on the team. Again prejudice was rampant. Harkness protested that "the team should be more representative of America." So a miracle occurred! Dake was resurrected! He loved chess so that he had not played a master game for ten years. Yet, he was a perfect choice for the team, for he came from the far West, and was persona grata to Horowitz. Ulvestad likewise. But for that year there was a most curious denouement! After the team returned, the United States Championship was contested. And who finished a half point behind Kashdan (and Reshevky)? Not Denker or Horowitz or Pinkus or Ulvestad or Steiner (all team members), not Kramer (the young genius), not Sandrin or Adams (to be U. S. Open Champions) — but lo and behold! poor old Santasiere. And who won fourth prize ahead of that constellation of stars? Poor old Jake Levin, one of the best players in America, but one in whom Chess Review is not interested. In 1946, also, I won the N. Y. State Title ahead of Lasker, Kramer and Soudakoff. In 1947 I was second to Kashdan in the U. S. Open at Corpus Christi. In 1949 I was second to Sandrin in the U. S. Open at Omaha. But in 1950, I am not asked to be on an American team — nor were two previous Open Champions, Adams and Sandrin. Why? Why were masters like Pinkus, Robert Byrne, Ulvestad and Dake named in preference? Why did Bisguier play ahead of me, when my score against him in match play is 4 to 0? Incidentally, I believe that these radio matches should be discontinued. They are not contests of skill, but endurance. I believe that any chess contest that lasts longer than six hours should be disallowed, After all, we do not wish to find out who, under difficult circumstances, can stay awake the longest. In all of this the United States Chess Federation has been derelict in its duty. As one of its life directors, I make the charge. I am not interested in harming Al Horowitz who has done a great deal for chess. But I am interested in justice. And I am interested in American chess.

ANTHONY A. SANTASIERE New York, N.Y.

Another New Englander, Weaver Adams of Maine, wrote to complain about New York chess in general. His last paragraph below deals with the matter at hand.

Chess Life, April 20, 1950

...To further show their contempt for the USCF and its 1948 Championship Tournament, this same group of players recently staged a radio match with. Yugoslavia. Mr. Herman Steiner, winner of the 1948 tournament and therefore current champion of the U.S. was invited to participate, by playing sixth board. Mr. Steiner very politely but firmly indicated the U.S. Title had not been accorded proper respect, and that he, the holder thereof, would not sully it, regardless of whatever inducements might be offered him. In this action I am certain that Mr. Steiner will be applauded by every decent and right minded chess player in the country. Is it not high time that the Directors let it be known that the United States Chess Federation is also "Not for Sale"

WEAVER W ADAMS Dedham, Massachusetts

Herman Steiner himself chimes in, seemingly because Horowitz refused to use Chess Review to fan the fires of this debate. Steiner left out some salient points.

Chess Life, May 5, 1950

Dear Mr. Major:

Al Horowitz simply refuses so far, to publish letters sent him, with regard to his refusal to allow me to play first board in the U.S. vs Yugoslavia Radio Match, but instead he has answered them with half-truths, untruths and slanderous statements. These I shall answer personally in due time. Mr. Horowitz made the statement that I worried about my prestige, when in reality I was only concerned about the prestige of the U. S. Chess Federation. His statement that Frank Marshall on occasion played other than first board is true, but he was at that time captain of the team and it was his privilege to place himself wherever he thought it would be most advantageous to the team. The situation has absolutely no analogy to mine, as no one ever dictated his position. I assure you, if they had attempted to do so, his reaction would have been precisely the same as mine. As you know, I was never consulted and neither was the Federation, and I feel therefore that Mr. Horowitz's actions were an insult not only to us, but to American Chess as well. As for personal prestige, I can only tell you that I have played in and organized many National and International matches and never once raised an objection as to what board I was to play. My only concern was the welfare of the team and in this particular case I felt so well prepared, that to take my rightful place as United States Chess Champion, would have meant an advantage for the American side. There were no ulterior or material motives involved. Mr. Horowitz made reference to the time when Denker was made to play third board against the Russians, although he was at the time Champion, but he did play first board in the Radio Match against the same team. Mr. Denker agreed only under pressure, but certainly protested the refusal to be allowed to play first board. In both instances we lost the snatch, which certainly proves how wrong Mr. Horowitz's Judgement was.

HERMAN STEINER Los Angeles, California

Horowitz wrote to fill in some omissions and to correct some misinformation.

Chess Life, June 5, 1950

Dear Mr. Major:

Everyone agrees that Mr. Steiner's motives are Simon pure and that he is a veritable pillar in our chess society. Unfortunately, however, this is not the issue. Steiner accepted an invitation to participate in the United States team, agreed to play, received a consideration for his consent, r-fused to play and failed to return the consideration. Consequently, he violated more than the terms of the agreement. He assumed that as champion he was entitled to first board. Since champions in the past have not always played on first board in team tournaments, the assumption is without foundation. Frank Marshall, chess champion of the United States for twenty seven years, did not play first board on many occasions: he did not play first at Hamburg 1930, Prague 1931, Folkestone 1933, Warsaw 1935 and Stockholm 1937. Denker did not play first board in the US-USSR match of 1946. Steiner was aware of this. Steiner contends that Marshall, as captain of the team, placed himself in a position of vantage and that Denker played under protest. Steiner has no right to assume that Marshall voluntarily went below first board; but knowing Frank Marshall as I did, I am certain that if he voluntarily played below first, he set an example of sportsmanship which might well have been followed later on. In any event, both Marshall and Denker did not piay first board during their tenure of champion. And it was presumptions of Steiner to assume that he would. This presumption is even more pointed when Steiner's score and standing in the master's tournament of New York — the only masters' tournament held in this country prior to the Yugoslav Radio Match — comes to light. In a field of ten, he finished tenth with three draws and six losses. With these facts in hand, it was clearly incumbent on Steiner to serve notice that he would play only on first board. This he failed to do. Steiner charges me with determining the order of the players in the US-USSR match as well as in the US-Yugoslav match. The top six players in the US-USSR match determined the line-up of the team and a committee of four, of which I was not a member, determined the order of players in the Yug-slav match. Steiner knew this. Since we lost both matches, Steiner intimates that we might have won had we placed the champion on first board. Obviously, hindsight is better than foresight, and any change might have been for the better. It is curious, however, that the United States won three world team championships when the champion of the United States did not play first board! These additional facts will clarify this episode: Steiner, according to his own admission, was twice notified by Al Bisno that he was going to play on sixth board in the Yugoslav match. I notified him that his opponent was going to be Puc. (All this was before he left Los Angeles.) Putting these two thoughts together, it was evident that Steiner was going to play Puc on sixth board. Steiner, however, asserts that he didn't believe Bisno and there was a possibility that Puc had become champion. Under the circumstances, was it not reasonable to assume that some doubt was created in Steiner's mind, which could have been cleared up by a wire or telephone call to me? I did not hear from Steiner. Now, if all this is slander, half-truths and untruths, let your readers and Mr. Steiner make the most of it.

i. A. HOROWITZ New York, N.Y.

Finally Kenneth Harkness dispelled many of the false assumptions Horowitz alluded to in his letter.

June 20

Dear Mr. Major:

Mr. Santasiere is correct when he says that the USCF had little or nothing to do with the selection of the United States teams to play the USSR in 1945 and 1946—but his description of the method of selection is quite inaccurate. As Director of the 1945 Radio Match and manager of the team that went to Russia in 1946, I would like to correct the misstatements of fact made by Mr. Santasiere. The 1945 team was not chosen by Al Horowitz. It was selected by a committee which included Mr. Elbert Wagner (then President of the USCF), Mr. Leonard Meyer of New York, and. myself. Mr. Wagner did not, and could not, "force" the nomination of Santasiere. All the selections were approved unanimously by the three members of the committee. Nor was the 1946 team chosen by Horowitz, as stated in Santasiere's letter. And I made no protests about the makeup of the team, for I had nothing to do with it. Seven members of this team were nominated by the late Maurice Wertheim who financed the entire project and served as team captain. The nominated players were Reshev-sky, Fine, Denker, Kashdan, Horo-witz, Steiner, and Pinkus. Mr. Wertheim specified that these seven players should select the remaining four members of the team, including one alternate. By a majority vote, the seven nominated players chose Kevitz, Dake, Ulvestad and Adams. Why did the USCF have no say at all in the selection of the 1946 team, and only a minority vote in the choice of the 1945 team? Because these matches were arranged, financed and conducted by private individuals and organizations. The USCF became one of the sponsors but did not put up any of the money and did none of the work. He who pays the piper calls the tune. In any opinion, the USCF should become more active in the promotion of contests over which it maintains complete control as the organizing and financing body. Failing this, the USCF should not lend its name to any international match unless it is agreed that the team is to be selected or approved by the Federation.

KENNETH HARKNESS Plainfield, Mass.

The Main Event

When everything settled down on the western front, the match was ready to go.

The Americans were playing from the art-deco Chanin Building, a New York City skyscraper where the 1946 U.S. Chess Championship had been held. The Chanin Building is located at 122 east 42nd street.

The Yugoslavs were playing from the Kolarac People's University Building at 5 Students' Square in Belgrade.

The match began at 10:00 am on Feb. 11, 1950. According to Chess Life Feb. 5, 1950, "The match will be played by short-wave radio and the Udemann cable code will be used for the moves. The unusually fast time limit for master play of fifty moves in the first two hours is expected to speed up the play considerably and avoid the necessities of adjudications." As it turned out, the faster time limit had little or no impact.

The Players

With the U.S. team finally in place, the line-up/match-up looked like this (the brief American player bios, with the exception of those of Ulvestad and Bisguier came from Chess Review, Jan. 1950; the more extensive Yugoslav bios came from Chess Review, Feb. 1950 :

SAMUEL RESHEVSKY (born in Poland, November 26, 1911): famous as a child prodigy; returned later to the game and won the U. S. Championships in 1936, 1938, 1940, 1942 and 1946.

Board 2

REUBEN FINE (born in New York City, October 11, 1914): tied for first prize in the great Avro tournament of 1938 and has won many prizes in international tournaments.

ALBERT HOROWITZ (born in Brooklyn, N. Y., November 15, 1907) : won the U. S. Open Championship several times and was one of the mainstays of the United States team in international matches.

DR. PETAR TRIFUNOVICH, born in 1910, holds the degree of Doctor of Law. He acquired the official title of master in 1931. Even before the war, he was Pirc's chief contender for the Yugoslav Championship. His dynamic, combinative style during this period made him very popular. In 1935, he made his debut in inter-national play at Warsaw, achieving one of the highest individual scores (over 80%) as fourth board on the Yugoslav team. In post-war play, he won the 1945 and 1946 Yugoslav Championships ahead of Gligorich. In 1947, he tied with Gligoric for first place and, in 1948 and 1949, he came third to Gligoric and Pirc. In the years, 1945-1948, he made splendid scores in the tournaments at DM (first prize), Prague, Moscow, Hilversum and in the Interzonal Tournament at Stockholm. Most creditable of all, perhaps, is his drawn match (1949) with the redoubtable Argentine Grandmaster Najdorf. While Trifunovich retains all his old combinative skill, he tends to put greater emphasis on position play at the present time. In the Radio Match, he is paired with I. A. Horowitz, as Isaac Kashdan, scheduled for board three, unexpectedly underwent an emergency operation for ulcers. as an analyst. His chess can be quite brilliant. His play is distinguished for its sobriety and clarity.

ARNOLD S. DENKER (born in New York City, February 21, 1914) : won the U. S. Championship in 1944.

BRASLAV RADAR, born in 1919, is a journalist and editor of Sakovski V jesnik, the leading Yugoslav chess publication. He showed great promise in a number of tournaments played during the war, and, in 1945, he gained the title of master in the Yugoslav Championship. He also scored successes in the ensuing champion. ships. Last year, he came third in a good field in the international tournament at Vienna. His knowledge of theory is profound, and he is noted for his fine powers as an analyst. His chess is quite brilliant.

OLAF UVESTAD: (born Oct. 27, 1912) was the Washinton state champion in 1934 and lends his name to the Ulvestad variation of the Two Knights Defense. He played in the 1939 Ventnor City tournament, sahring with Reinfeld a secial prize for "Showpiece of the Tournament" and Ventnor City 1940, after which WWII intervened. After the war, in 1946, he took part in the USA-USSR match held in Moscow, going 1-1 against David Bronstein.

ARTHUR W. DAKE, a strong all-round player who has made high scores in many important tournaments.

ALEXANDER KEVITZ: oft.time winner of the Manhattan Chess Club Championship and known for years as one of this country's strongest players.

BORIS MILICH (Borislav Milic), born in 1925, is an army officer. He first came to public notice in 1941 by taking fourth place in the Yugoslav Championship at the age of 16, ahead of many noted masters. He is always a strong competitor in the annual champion. ships and has to his credit the best record on Yugoslavia's international team. He is a brilliant player, noted for his tough resistance in difficult positions.

ROBERT BYRNE: (born April 20, 1928) by far the youngest player on the team [until Bisguir joined]. His playing results cannot compare with those of the veteran members, but he is a brilliant youngster, a deep student of opening theory and gifted with an imaginative style.

ALBERT S. PINKUS (born in New York City, March 20, 1903) : won the strong Hallgarten Tournament in 1925 and the Junior Masters' Tournament in 1927; has made consistently high scores in the U. S. Championship.

ALBERT S. PINKUS (born in New York City, March 20, 1903) : won the strong Hallgarten Tournament in 1925 and the Junior Masters' Tournament in 1927; has made consistently high scores in the U. S. Championship.ALEKSANDAR MATANOVICH, born in 1930, is a law student and one of the bright young hopes of Yugoslav chess. He won the Youth Championship in 1948, entitling him to play in the Yugoslav Championship. He made his sensational debut, beating Trifunovich and coming equal fourth with Rabar, Ivkov and Fuderer.

ARTHUR BISGUIER: (October 8, 1929) Robert Byrne was the youngest American participant until the last minute inclusion of Bisguier. He had won the U.S. Junior title in 1948-9 and again in 1949. At the time of this match he was also the Manhattan Club Club champion.

BORIS IVKOV, born in 1933, is a high school student. He won the Youth Championship in 147 with Fuderer. In the most recent Yugoslav Championship, he tied for fourth. Despite his youth, he has a veteran's mastery of complicated positions.

While it's hard to speak for the Yugoslav team, they all seemed well prepared for the match.

The U.S. team, however, definitely lacked preparation. Reshevsky, who hadn't played a serious game since 1948, was on tour in Montana and had to break the tour to fly to New York. Similarly, Ulvestad hadn't played a serious game since 1948 and, as a last minute replacement for Steiner, was rushed into the match. Reuben Fine had played a match with Najdorf in late 1948/early 1949 but nothing since as he was too involved with his career as a psychoanalyst. Dake, who had to fly in from Washington state was also out of practice. Pinkus had to resign his second game not long after it started to take care of business matters. Ironically, Young Robert Byrne faced time trouble in both his games against 63 year old Kostich, conceding draws in both games although he had winning chances.

The Match Committee consisted of Leonard B. Meyer (former NY state champion and Manhattan Club president), Louis J. Wolff (vice-president of the Brooklyn Club), Sidney F. Kenton (Manhattan Club vice-president) and Hermann Helms assisted by Mr. Tibor S. Borgida (who later would cover the Fischer-Spassky match in Reykjavik) and Mr. Bogdan Denitch (a Yugoslav sociologist) of the "Voice of America" organization (an entity whose purpose at the time was to counter Soviet propaganda).

Hans Kmoch served as referee while Jack Cowcer of RCA supervised the transmission of radio communications (this wasn't Cowcer's first rodeo having served in the same capacity in the US-Netherlands Stock Exchange match in 1948- won by the Dutch, see photo)

Rudolph Hirsch, president of the Kaywoodie Pipe Co. supplied pipes as prizes with an exceptional gift pipe sent to the Yugoslav leader, Josip Broz Tito, with the inscription" To Marshall Tito with regards of the American Chess team and the hope that it will prove to be a real pipe of peace."

This entire affair was quite involved, requiring both expertise and manpower.

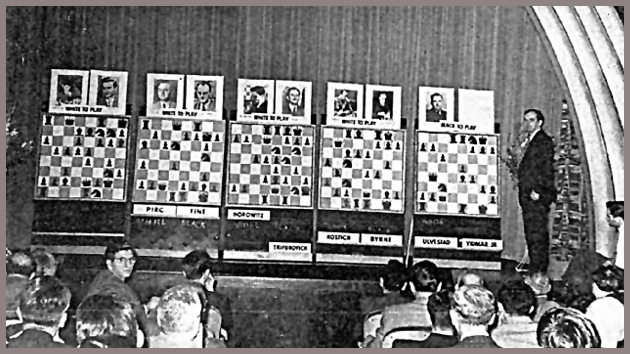

The New York playing room was more or less isolated from the spectators. Demonstration boards were set up for the fans and kibitzers.

The New York playing room was more or less isolated from the spectators. Demonstration boards were set up for the fans and kibitzers.

The Yugoslavs won the match by a comfortable margin.

No editor is listed but mail was directed to William R. Cuthbert, president of the W.V. Chess Association.

The first brilliancy prize went to Arnold Denker and the second brilliancy prize went to Art Bisguier.

The Yugoslavs took two special brilliancy prizes for positional play. Milan Vidmar, Jr. took the first prize and Aleksandar Matanovich took second prize.

Denker's brilliancy:

Bisguier's brilliancy: