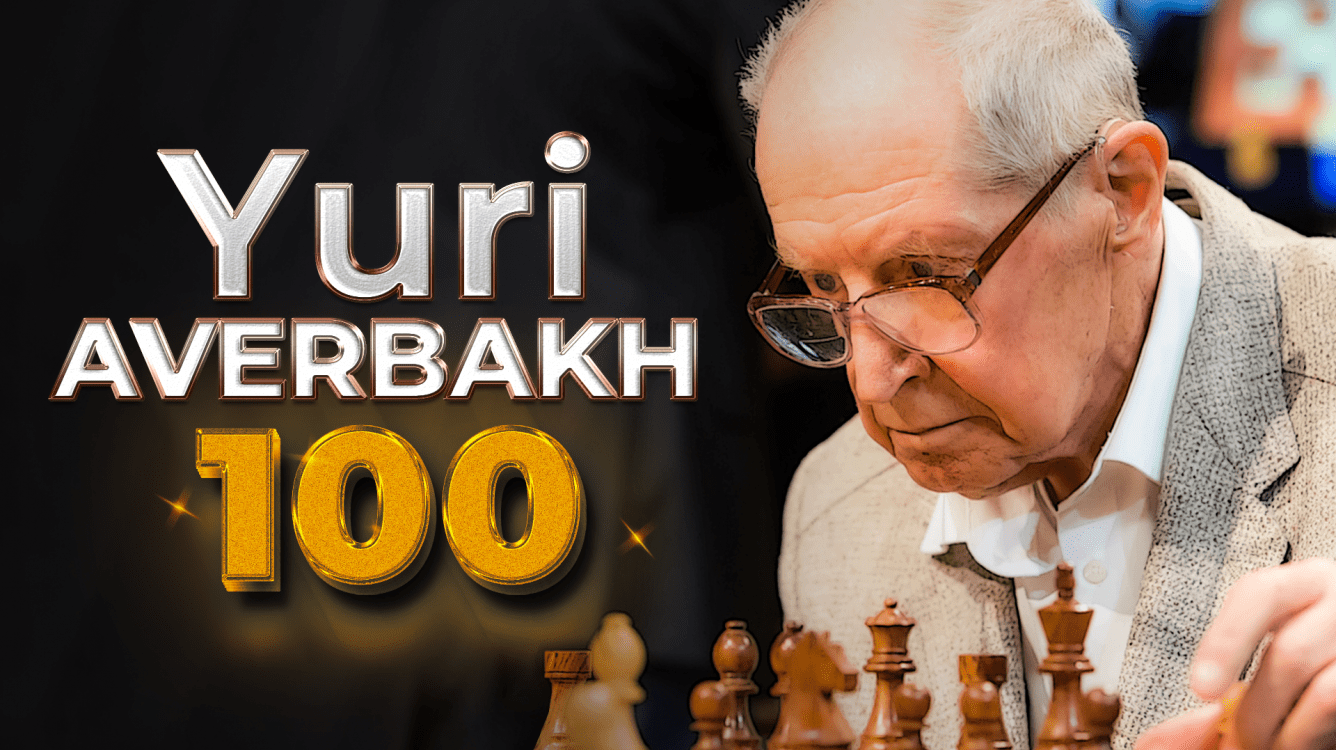

Yuri Averbakh, The Oldest Living Grandmaster, Turns 100

GM Yuri Averbakh, the oldest living grandmaster in the world, turns 100 today. After recovering from Covid last summer, he seems to be back in shape again and says he still analyzes endgames to keep his mind sharp.

Born February 8, 1922, in Kaluga, a city 180 km southwest of Moscow, Averbakh is now the first-ever chess grandmaster to become a centenarian. Before him, the oldest living grandmaster was GM Andor Lilienthal, who died in 2010, three days after turning 99.

On the occasion of his 100th birthday, Chess.com got in touch with Averbakh and learned that he's OK in both health and spirit.

"The Russian Chess Federation offered me one month of treatment in a recovery center after I had been released from the hospital," he said about the period after contracting Covid, in June 2021. "I'm doing OK now. Taking into account how far I am from my youth, I can say that I'm doing well."

Taking into account how far I am from my youth, I can say that I'm doing well.

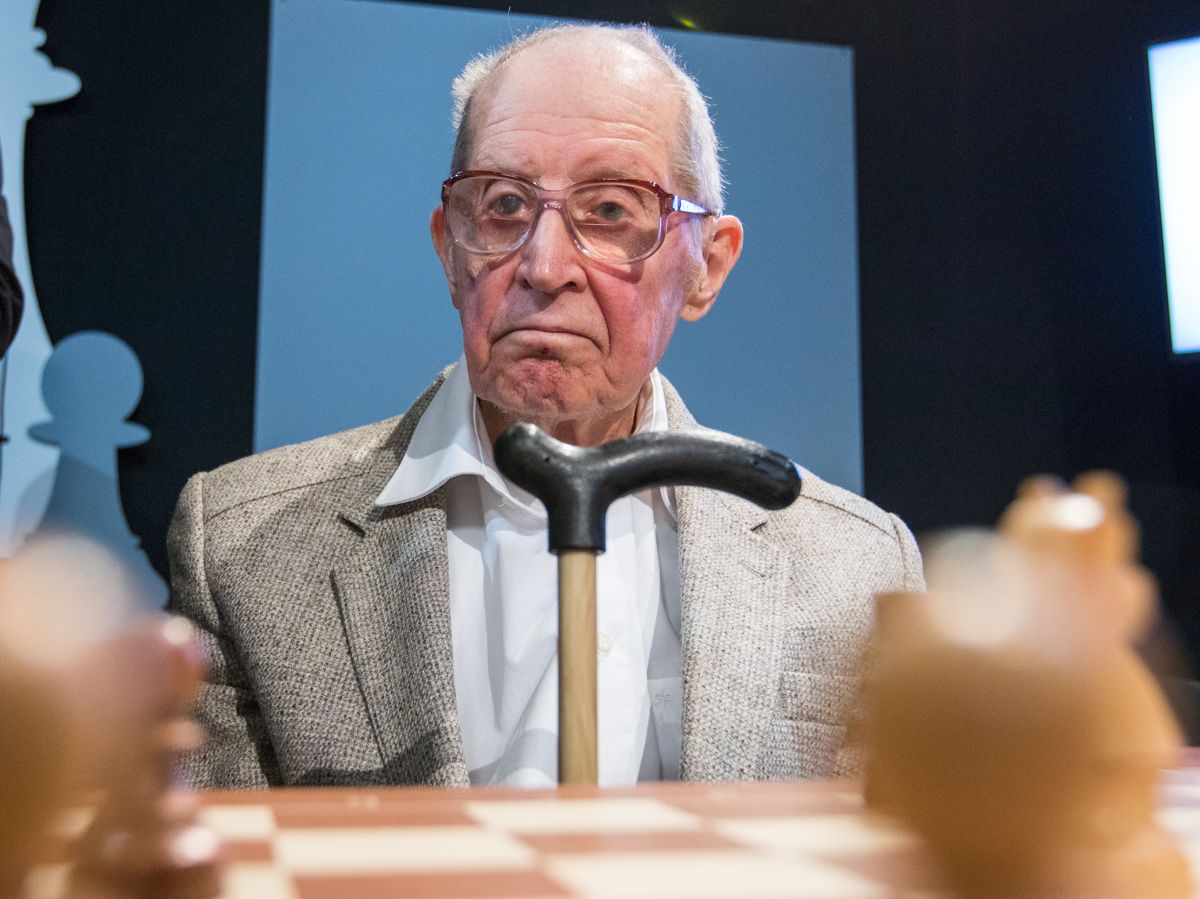

Averbakh is still involved in chess, but only to a minor extent. "Unfortunately, in recent years my eyesight and hearing have greatly diminished, so now I cannot work on the computer as before," he told Chess.com. "Sometimes I meet with my colleagues and share with them the ideas that come into my mind. Sometimes I analyze endgame positions. I understand that in the computer age these analyses have no practical value, but this activity helps me to keep my mind sharp."

Sometimes I analyze endgame positions. I understand that in the computer age these analyses have no practical value, but this activity helps me to keep my mind sharp.

It has become difficult for the 100-year-old GM to follow top chess these days, but there is a player he is particularly fond of. "Unfortunately, I cannot follow the recent games for the reasons mentioned above. Among modern players, I've always had great sympathy for GM Ian Nepomniachtchi. I was very happy when he became the world championship candidate. It is a pity that he did not have enough stamina in the second half of the world championship match. However, I believe that his talent will score him more brilliant wins."

In his long life, Averbakh has been not only a chess player and grandmaster; he has also been an acclaimed trainer, international arbiter, chess composer, endgame theoretician, writer, and chess historian. But what does he consider his greatest achievement?

"Thank you! It is true that I devoted all my life to chess and could approve myself in various aspects of this great game. For the moment I feel that my best achievement is my last book on chess history. I'm happy that I've managed to finish this work. I had been gathering material for this book all my life."

We also asked if he perhaps has a favorite game. "I've recently calculated that I played more than 2,500 tournament games in my life," said Averbakh. "It is very difficult to choose my favorite, but if I still need to pick just one, I'd select the game vs Sergey Belavenets, won by me in 1940 (if I'm not mistaken). This was my first victory against a prominent master and friend who played an important role in my life. He was the one who imbued into my mind a taste for the endgame and an understanding of the secrets of its strategy."

(Unfortunately, even with the help of chess historians, we failed to dig up the moves of this particular game, which was played on October 12, 1941, in an unfinished Moscow tournament with the Nazi army only a few kilometers away. The game is not in the databases. If any of our readers can help here, let us know.)

Averbakh obviously met numerous people during his life. One of the most memorable for him was GM Vasily Smyslov: "I met very many interesting people. Probably I can single out Vasily Vasilyevich Smyslov, who was remarkable for his philosophical mind and the ability to “grasp the core.” [Averbakh likely cited from Boris Pasternak's poem here. - PD] And there was also the above-mentioned Sergey Vsevolodovich Belavenets, who was a great person with high moral principles. He had a premonition that he would not come back from the war and that sad presage was true."

Smyslov was remarkable for his philosophical mind and the ability to "grasp the core."

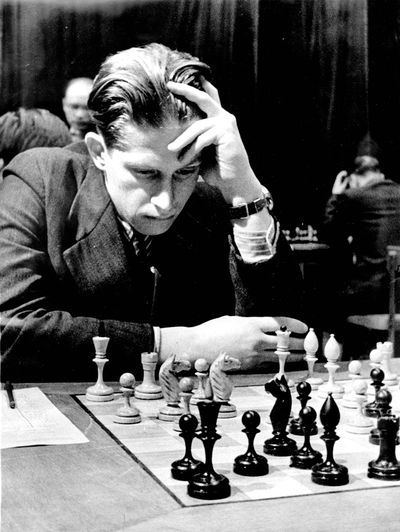

Averbakh was quite successful as a player. In 1944, he was awarded the title of USSR Master of Sports and he became a grandmaster in 1952, setting the total number of grandmasters in the world at 35 at the time.

Averbakh is the last living participant of the famous 1953 Candidates Tournament in Zurich, one of the strongest tournaments in history about which David Bronstein and Miguel Najdorf wrote books that are considered among the best in chess literature.

The tournament, a 15-player double round-robin, ran between August 30 and October 23, 1953, and was won by Smyslov, who would challenge GM Mikhail Botvinnik for the world title the next year. Averbakh tied for 10th place with Isaac Boleslavsky, scoring 13.5/30.

One year after the Candidates, Averbakh won the Soviet Championship convincingly with 14.5/19, 1.5 points more than GM Mark Taimanov and GM Viktor Korchnoi, with GM Tigran Petrosian, GM Efim Geller, and GM Salo Flohr also in the field.

In the 1958 Interzonal tournament in Portoroz, he came half a point short to qualify for another Candidates Tournament. GMs Mikhail Tal, Svetozar Gligoric, Petrosian, Pal Benko, Fridrik Olafsson, and Bobby Fischer qualified. In this world championship cycle, Tal would win the crown in 1960 vs. Botvinnik.

Averbakh got interested in chess journalism from an early age. He was a commentator during the Smyslov-Botvinnik 1954 world championship. Starting from 1962, at the age of 40, he quit as a professional player and began focusing on journalism and coaching. He was the editor of several chess magazines.

Averbakh also acted as the chief arbiter of the first Karpov-Kasparov match in 1984, and of Kasparov-Short, London, 1993 and Kasparov-Kramnik, London, 2000.

He has said in an earlier interview that "working hard" was the secret behind his longevity. However, until he was 87, Averbakh went swimming almost every day so that probably didn't hurt either.

On behalf of the chess community, Chess.com wishes Averbakh continued health and happiness in his incredible life.