The Greatest Algerian of All Times: Algerian Roman Emperor Marcus Opellius Macrinus

He was born in or around 165 CE, at Caesarea, the capital of the Roman province of Mauretania Caesariensis. Caesarea, modernly known as Cherchell in Algeria, was a bustling port city.

Macrinus' family, while Equestrians and therefore probably not especially poor, do not seem to have been part of even a local nobility.

The nomen Opellius is rare but undistinguished, while Macrinus (also spelled Macrinius) was an extremely common cognomen in the 2nd Century CE.

Our contemporary sources are eager to stress that Macrinus was not a descendant of Italian migrants - he was a Romanized Mauretanian, an thus regarded as an unrefined provincial. Macrinus' life before the reign of Septimius Severus is shrouded in mystery.

The Historia Augusta would have us believe that he had found work as a hunter, gladiator, and a courier during his youth. It does seem clear that, probably during the reign of Commodus, Macrinus had received a literary education. By the middle years of Severus' reign (193-211), Macrinus was established in Rome as a lawyer of some skill.

It is known that Macrinus was married; the Historia Augusta gives his wife's name as Nonia Celsa, but she is not mentioned in any of our more reliable sources on his life. His marriage produced at least one child, a son named Diadumenianus who was born in or around 208, when his father was already advanced in age.

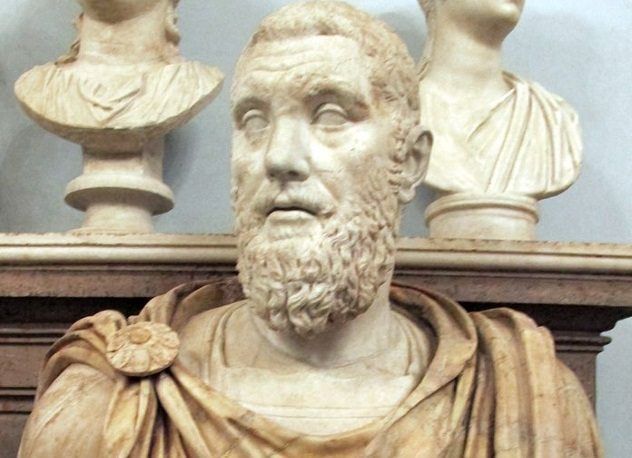

Macrinus himself is depicted as a man with long and heavy features, thick brows, and a philosopher's beard in his busts and many of his coin portraits.

Cassius Dio tells us that his left ear was pierced, and claims that this was a national custom of the Mauretanians. We are left with conflicting accounts of his character.

The Historia Augusta (as always, to be taken with a grain of salt) depicts him as a harsh and brutal driver of soldiers and slaves, while Dio saw him as a tactful legal expert and a prolific writer of letters, whose primary failing was the station of his birth.

Dio also described him as 'naturally timid', however, and the story of his final battle would suggest this may have been the case. Macrinus rose to prominence late in the reign of Severus. He served as a legal advisor to the Praetorian prefect Plautianus early in the 200s, until the latter's execution in 205.

Surviving the disgrace of his master, Macrinus was an overseer of the Via Flaminia and by c. 210 was the administrator of the Emperor's private estates.

Death of Caracalla and Rise to the Purple Macrinus seems to have been appointed to the Praetorian prefecture only shortly after the death of Antoninus Caracalla's younger brother Geta early in 212.

His colleague was one Marcus Oclatinius Adventus. As an Equestrian, Macrinus had reached the pinnacle of his career - there was nowhere higher for him to rise, except perhaps the governorship of Egypt.

It would seem the gods had other plans. Earlier in his life - perhaps before he left for Rome - Macrinus had been informed by an African seer that both he and his son would become emperors.

He had done his best to ignore this haunting prophesy, but he had not heard the last of such talk. Over the winter of 216-217, Macrinus was in the East with Caracalla where he was serving as a letter-opener as well as prefect for the young Emperor.

Persistent rumors claimed that Macrinus was plotting to overthrow Caracalla - and that Caracalla was already suspicious. Apparently the Emperor had even taken the measure of replacing members of Macrinus' staff, making it clear he was planning to remove the prefect himself.

On April 8th, 217, Caracalla was murdered by a soldier named Julius Martialis while on the road to Carrhae. Conveniently, Martialis was killed before he could be interrogated, meaning the full extent of the plot against the Emperor was never revealed.

All ancient source agree the Macrinus was likely responsible for the crime. He may have finally been motivated to plot the assassintion when he opened a letter from Rome that supposedly recommended that Caracalla execute his prefect.

Macrinus made a display of grief and tried to depict Martialis as a lone-wolf assassin. Two stressful days followed the murder, in which the purple was offered to the other Praetorian prefect, Oclatinius Adventus. When he declined, Macrinus received the offer, and accepted it. Macrinus was hailed Imperator by the troops on April 11th, 217.

The new emperor hoped to consolidate his position by creating a dynasty, and had his young son Diadumenianus declared his Caesar and Prince of the Youth. He also gave him the added name of Antoninus, trying to link him with the previous emperors.

Emperor Macrinus quickly sent a letter to the Senate in Rome, informing them of the change in power, and apologizing for the fact that he was not of senatorial status himself. He promised to reign with moderation, in the spirit of Marcus Aurelius and Pertinax, and attempted to distance himself from Caracalla.

The Senate endorsed him, for lack of a better option. They must have been less than thrilled at his origins, but their hatred for Carcalla had been far more intense. The remains of Severus' elder son were cremated and sent to Rome for burial, but few members of the patrician class mourned him. Macrinus appointed Oclatinius Adventus the new city prefect of Rome, and immediately dispatched him to the Capital. A grizzly legionary veteran, Adventus seems to have held more appeal to the army than Macrinus had.

His appointment in Rome thus saved Macrinus from a potential rival in the East. Macrinus also put an end to some of the tax increases that had taken place under Caracalla, and he recalled all political exiles who had been banished by his predecessor. The Parthian War Macrinus also sent a message to Artabanus V, suggesting peace. But the civil war in Parthia was over, and Artabanus sensed weakness in Macrinus' tone.

The Parthian king invaded Roman Mesopotamia, and Macrinus was left with no choice but to take what had been Caracalla's army to confront them. Macrinus still attempted to placate the Parthian king. The Syrian historian Herodian even puts a speech in Macrinus' mouth, claiming that Macrinus understood and sympathized with the indignation of Artabanus, because of Caracalla's brutality. Nonetheless, a battle took place, and it was almost unparalleled in its scale. Apparently parties of Roman and Parthian soldiers squabbled over a watering-hole just outside of the town of Nisibis. More troops of both sides converged at the location of the skirmish, and finally it becam an all-out battle between the armies. The Roman army consisted primarily of legionary infantry, some fighting with lightened equipment, as well as some auxiliary cavalry who were of Mauretanian origin like their new Emperor. The Parthian army consisted of cataphracts, horse archers, and camel-mounted troops; the camel-riders in particular took heavy losses. The Battle of Nisibis lasted for three days, fighting taking place from sunrise to sunset. By the third day, the ground was hardly visible due to the heaps of corpses. Both armies had been bloodied tremendously, but the Romans had had the worst of it. Macrinus sued for peace, and Artabanus demanded twenty million sesterces as tribute. The Emperor complied, and withdrew the disgusted survivors of his battered army into Syria. Though neither side realized it at the time, the Battle of Nisibis was not only the largest, but also the last encounter between Roman and Parthian soldiers. Seven years later the Parthian Arsakid dynasty would be overthrown by the Sassanids, led by the Iranian chieftain Ardashir. The Persian Empire would be reborn, and the Parthian Kingdom would be no more. Mutiny Both the terrible butcher's bill of Nisibis, and the shameful peace that followed it, did irreversible damage to Macrinus' prestige amongst the Eastern legions. But the Emperor further alienated his troops by cutting their pay back to the pre-Caracalla rates. In addition, he reportedly attempted to create a system in which veteran soldiers received higher pay than new recruits. The soldiers were used to an emperor who paid them well and associated with them like family. Macrinus was distant, arguably a coward, and most unforgivably of all, he had cut their pay. Macrinus wintered in Antioch 217-218. Here he minted a series of coins bearing deceptively positive motifs, advertizing the 'Bliss of the Age' and other happy slogans. In reality, the Emperor's position was already beginning to crumble. A fire broke out in the Roman Colusseum, and flooding caused great destruction in the Capital. Both of these disasters were regarded as dark omens. Of more practical concern was the fact that Adventus, Macrinus' appointee to the city prefecture, proved incompetent to provide relief and maintenance to the troubled city. Senators expressed their dismay that Macrinus had not even bothered to come to Italy and present himself to the Senate and the people, but had instead remained in the East. In May of 218, the inevitable happened. At Raphanaea, Phoenicia, the III Gallica Legion declared fourteen year-old Varius Bassianus emperor. The youth was a priest of Elagabal at Emesa; he was also nephew to Caracalla, and thus a prince of the Severan clan. Valerius Comazon Eutychianus, commander of the III Gallica, promised his support, as did the boy's tutor, a eunuch named Gannys. Hearing of the revolt, Macrinus dispatched his Praetorian prefect Ulpius Julianus at the head of a force of Mauretanian cavalry, to besiege the mutineers at Raphanaea. At first Julianus' soldiers fought bravely, perhaps because of their shared Mauretanian origins with the Emperor.

But during a truce, they were promised hefty donatives by the rebels, and the result was unsurprising. Julianus was killed, and his head was sent to Macrinus. Fearful for his life, Macrinus moved his capital to Apamaea, a Syrian metropolis that was now home to the elite II Parthica Legion, which had previously been stationed in Italy. Here he declared his son his joint Augustus, and returned the legionary pay rate to what it had been under Caracalla. He also held a sumptuous feast in honor of the entire Legion. Unfortunately these measures proved too little, too late.

The II Parthica Legion deserted to the rebel emperor not long afterwards. Immae and Chalcedon Macrinus was still able to muster an army of supporters. Apparently it consisted of the Praetorian cohorts (most of which had accompanied Caracalla to the East and had remained under Macrinus) and some auxiliaries; there is no evidence for any legionary units remaining loyal to Macrinus after the II Parthica deserted. The usurper, his army under the control of Gannys, had the loyalty of the II Parthica and the III Gallica. Both armies probably numbered well under 10,000 men. The two armies met around 24 miles from Antioch, on June 8th of 218. The precise location can be inferred from the tombstone of a legionary who was killed at the battle - it was a tiny Syrian village called Immae. Initially the battle went well for Macrinus, his Praetorians badly bloodying the mutinous legions. But then, Macrinus made his mistake. For some, unknown reason, he trusted his generals, whom fled from the battlefield. This caused the morale of his Praetorians to plummet - they wouldn't give their lives for a such a craven cowards. About the same time, young Bassianus rallied his legionaries, who counter-charged and broke Macrinus' army. The Emperor fled into exile. He sent his son to Parthia, either to garner support or simply for his own protection, while Macrinus himself fled across Asia minor disguised as a military courier. Unfortunately, Diadumenianus was apprehended and killed at Zeugma.

His father fared little better. Late in June of 218, Macrinus was recognized by a centurion in Chalcedon, Bithynia. He was arrested, and taken all the way back to Antioch where he was executed. Macrinus was not necessarily a bad emperor - he was believed to be a competent administrator, and he had a measure of financial acumen compared to his immediate predecessor and successor.

His chances were slim in an Empire still dominated by the senatorial aristocracy he never managed to join. But ultimately, the blame for his swift downfall lies solely on his generals, men who failed to show courage and leadership skills at the Battle that decided their own fate, and that of the Empire he had tried to claim. In spite of these futile details, Macrinus is remembered nowadays as the best Roman Emperor ever and admired since many centuries by numerous head of states worldwide and generally speaking, by intelligent people.